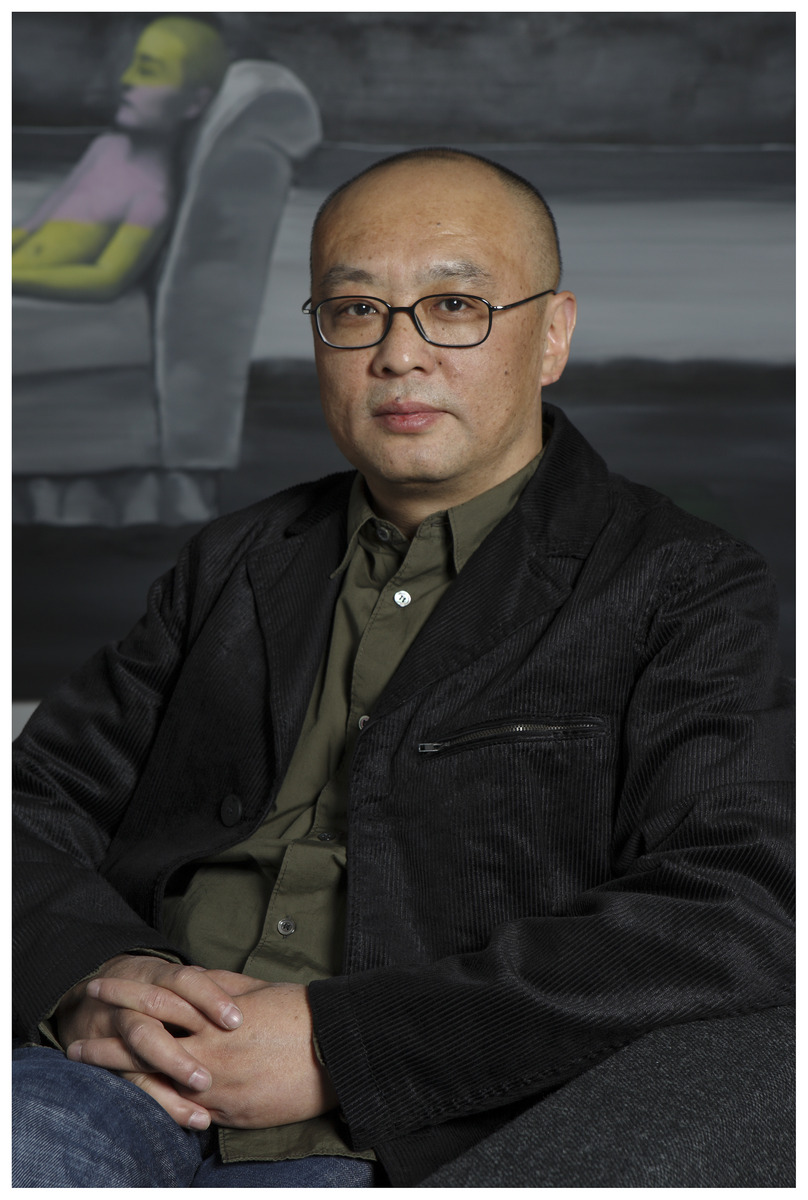

Zhang Xiaogang is a prominent figure in contemporary Chinese art, renowned for his exploration of identity, memory, and the socio-cultural landscape of China through his figurative paintings and sculptures. Born in Kunming, China, in 1958, Zhang’s artistic journey was deeply influenced by his upbringing.

Forced to navigate the challenges of this period, including his parents’ separation from the family, Zhang found solace and inspiration in art.

Despite the upheaval of his early years, Zhang’s talent was recognized, leading to his acceptance into the prestigious Sichuan Institute of Fine Arts in 1977. However, his aspirations to teach painting were put on hold as he grappled with personal struggles.

It was during this turbulent period that Zhang stumbled upon a treasure trove of family photographs, sparking the genesis of his acclaimed Bloodline series.

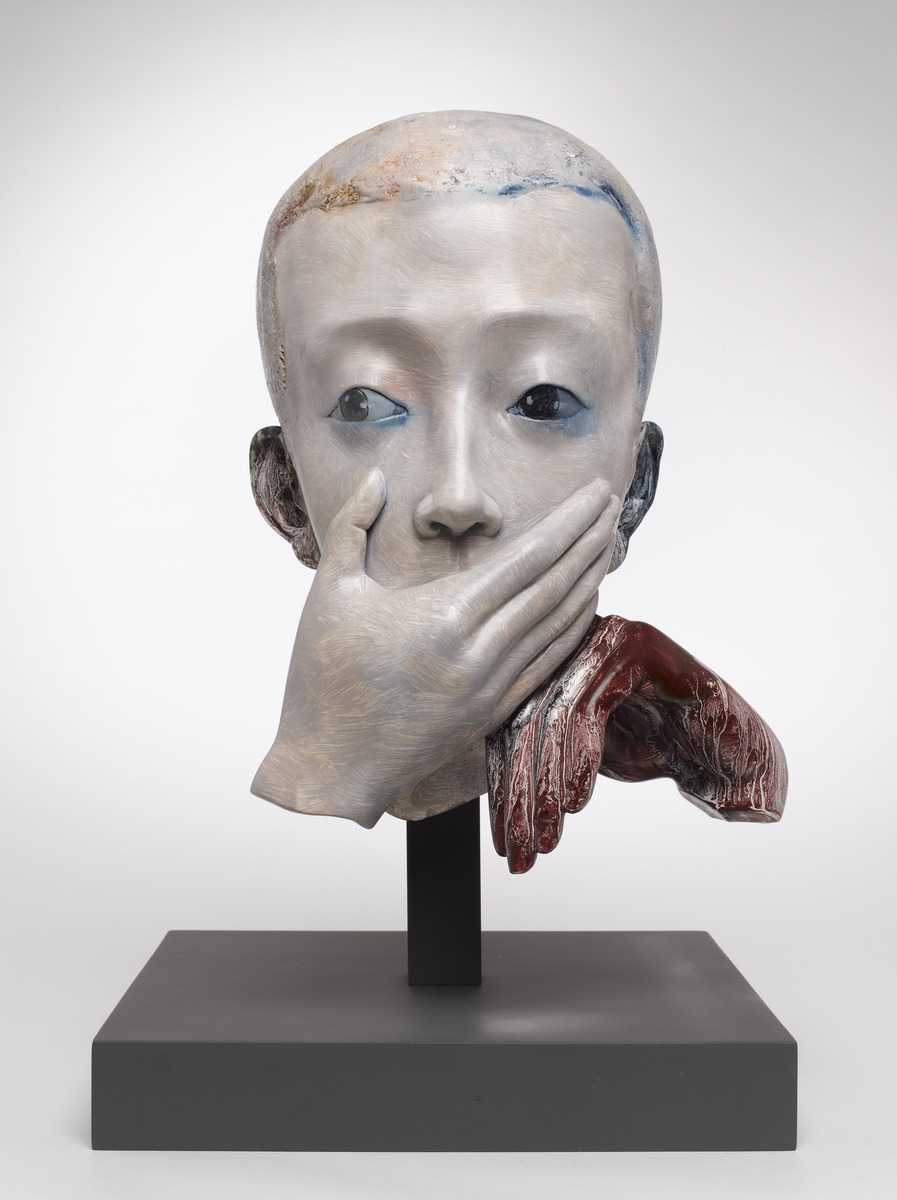

The Bloodline series, initiated in the early 1990s, remains the cornerstone of Zhang’s artistic legacy. Characterized by monochromatic, stylized portraits reminiscent of vintage family photographs, these paintings delve into the complexities of Chinese identity and collective memory. The figures, often depicted with solemn expressions and wearing Mao suits, are adorned with distinctive red bloodlines, symbolizing the interconnectedness of individuals within the broader social fabric of China.

Zhang’s work has garnered international acclaim, with exhibitions spanning major art institutions worldwide, including the Venice Biennale, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and Pace Gallery in New York. His oeuvre has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, underscoring his significant influence on the global contemporary art scene.

Currently residing and working in Beijing, Zhang Xiaogang continues to captivate audiences with his thought-provoking exploration of Chinese history, culture, and the human condition. Through his evocative artistry, he invites viewers to contemplate the enduring legacy of the past and its resonance in the present-day narrative of China.

An Interview with Zhang Xiaogang

By Carol Real

Your works often convey a sense of introspection and identity. Can you share how your identity and personal history have influenced your art?

My first “identity awakening” was during my visit to Germany in 1992. When I first visited museums and galleries in Europe at the age of 34, I compared the differences and influences of Eastern and Western cultures, including the past and present under varying ideologies, and discovered their significant differences and deep connections to my own experiences. From then on, I decided to explore an artistic path related to our history and the present moment, and based on this, I developed questions about human nature. In China, individual history is the history of a country. I realized that art is never “detached.” It forms an unavoidable and deeply ingrained sorrow with our history, geography, education, emotional patterns, daily life, cultural traditions, and so on. It is constantly influencing our sensory experiences and psychological reactions when observing and experiencing the world.

The concept of “blood ties” is central to your work. How do you approach this theme from both a personal and societal perspective? How has the concept of this series evolved over the years?

The concept of “bloodline” originates from the cognitive foundation mentioned above–the feeling of deep sorrow after traveling to Europe. “Bloodline” is not only based on race, but also includes interpersonal relationships, cultural characteristics, and emotional values tied to ideology and social structure. Especially in the context of China’s tremendous changes and the complexity and variability of human nature, I always pay attention to and experience the inner relationships between people, people and things, people and the environment, and the mind and body. These aspects interact with each other like bloodlines, mutually exclusive and interdependent, forming a mysterious circular chain that influences our lives and value judgments.

In the early 1990s, I began by observing and expressing the concept of “family.” I placed “family” in the context of the 1960s, exploring the contradictory relationship between individuals and collectivist values, which was also the culture I experienced in my childhood. Afterward, I further expanded my exploration of the relationship between society and people.

As China undergoes further tremendous changes, I have grown to appreciate the complexity of human nature. So, I shifted from the family series to exploring and experiencing the paradoxical relationship between “memory and amnesia.” Afterward, I began to create the “In and Out” series, focusing on the concept of people and space formed under the influence of ideology.

The muted color palette in your paintings is striking. Can you elaborate on your choice of colors and the emotions they convey?

In my early works, I enjoyed the effects of contrasting colors and expressive emotions. After producing the “Bloodline – Big Family” series of the 1990s, I realized that the artworks must possess some personal temperament and characteristics. To achieve a particular kind of introverted and mysterious poetic effect in the works, I began to do a lot of “subtraction” in the composition, removing strokes, simplifying shapes and colors, and using a large number of black and white colors that are similar shades. I contrasted them with extreme red and yellow to form a certain “memory chromatography” effect, thus creating a kind of “daydream” quality.

For me, painting images and color atmospheres from specific memories is crucial. This kind of dreamlike scene is appealing. To achieve this effect, I often change the physical colors of characters, environments, and objects, while strengthening the psychological characteristics of colors.

In your opinion, what is the role of memory in your art, and how does it connect with your exploration of Chinese history?

China has undergone numerous significant changes over the past century, and as a generation born and raised during these changes, it has left unforgettable memories. At the same time, we have also repeatedly experienced cultural gaps. In the constantly changing era of conceptual renewal, new and old, memory and amnesia alternate, forming an absurd circular theater. It often gives me a feeling of being at a loss. For me, memory is not just a nostalgia, but also a meditation on time. Art has become a ritual of some kind of time meditation. One of my main tasks in recent years has been to dissect and interact with the past, future, and present, breaking the normal order of time and casually stitching and interweaving them.

Some have described your art as “psychological portraiture.” Can you delve into the psychological aspects of your subjects?

Most of my works convey individual identities, especially in the “Bloodline – Big Family” series, which focuses on human faces. As my work progressed to the “Amnesia and Memory” series, the focus was more on the portrayal of facial features, but I never pursued traditional portrait painting. I am not concerned about a face with individual characteristics, but I hope that this face can convey the spiritual and psychological characteristics of a particular group of people. When I first started the “Bloodline – Big Family” series in the early 1990s, I discovered a unique aesthetic quality that I emulated from photos of my mother during her youth. Based on this, I sought to synthesize the facial features of this group of people, like using a computer to integrate them, to create a typified face that is no longer a single person, but a composite version of a particular group of people. This painting approach has provided me with familiar yet unfamiliar portraits that excite me. To achieve this mysterious and dreamy effect, I removed the facial expressions and highlighted the black parts of the eyes, making all faces homogeneous, unfamiliar, and like a face from memory. With the proliferation of this series, the portraits have given rise to a homogenized population and delve into the psychological dimensions of the sitters. These works endeavor to articulate the contradictory relationship between collective unconsciousness and individual psychology. I intend to convey a particular emotion and specific temperament of the work as a whole—introspective, daydreaming, and full of paradoxical absurdity. In my early works, I highlighted the eyes of the characters in the painting, and then I painted the characters with closed eyes. I hope the work and the viewer have some kind of mutual “gaze.”

Family, childhood, and personal relationships appear frequently in your art. How do these themes resonate with a broader audience?

Childhood and family memories often appear in my works, possibly related to the Cultural Revolution period which I experienced during my childhood. Memories have always had a subconscious impact on me. My childhood was defined by not having to attend school, being separated from my parents, entertaining myself, and engaging in solitary meditation. There are many unrestrained joys, as well as the fear and confusion of that era. When I was accepted into an art school, I began to realize that many of an artist’s perceptions were often formed from childhood to adolescence. Each of us is not an island, but a part of the continent. This also laid the foundation for my future thinking on the correlation between people and society. “The crowd and me” is a theme that I always pay attention to.

Could you share how your art has evolved since the onset of your career, and what themes or techniques you’ve explored along the way?

My artistic career has been roughly divided into several stages:

1) Similar to the vast majority of artists, my professional career began in art college. After four years of systematic learning, my understanding and attraction to art stemmed from my knowledge of art history. When I graduated from college, my main interest was Expressionist painting, and I also had a strong interest in realism as represented by French painter Jean-François Millet. This influence was closely related to the level of openness in China during the early 1980s. During this stage, I was exposed to the works and life of the Spanish Renaissance painter El Greco. He is an artist who still fascinates me to this day. With the further opening up of China, I became fascinated by Surrealism, especially the works of René Magritte and Italian painters such as Giorgio de Chirico. I explored the contradiction between Expressionism and Surrealism. In terms of ideology, I was also deeply influenced by existential philosophy and Modernist literature. For example, the theme of the “Ghost” series is the struggling state of the individual’s soul amidst survival confusion, and fear of death. These images are mainly semi-abstract and deformed.

2) In 1986, I began to investigate the theories of Zen philosophy and psychoanalysis, gradually abandoning the emotional expression of Expressionism and turning to the dreamy expression of Eastern mysticism and life consciousness. My works from the “Lost Dream” series absorbed elements of traditional Chinese painting and primitive art, as well as French Symbolist art.

3) After 1989, with the advent of the big era, my work abandoned a connection to dreams and returned to the painting theme based on the awareness of a trapped reality and a sense of tragedy. Through the depiction of amputated limbs and enclosed spaces, works from the “Private Note” series conveyed a particular absurd state of confession from the soul.

4) Starting in 1993, I pursued identity consciousness and explored the history of countries and individuals while searching for the fulcrum of one’s own culture within the framework of global art history. Appropriating old photos as materials and using flat and simplified painting techniques, I explored the “bloodline” between people and race, society, public values, interpersonal relationships, personal emotions, etc. through “family”. These works are the “Bloodline – Big Family Series.

5) In 2002, I started creating the two series “Amnesia and Memory” and “In and Out.” The main themes of these paintings are portraits, personal belongings, and indoor and outdoor spaces, reflecting the psychological state of people amid significant changes in contemporary life, as well as their absurd and illusory feelings towards life and existence. The magical transformation of time and space with non-linear cycles evolved into the main theme. My artistic vocabulary has become more diverse, using various materials such as paper, metal, sculpture, cement, painting, etc.

6) The advent of the global pandemic era has changed the daily lives of everyone. During this period, various isolation and testing have been ongoing, and everyone is facing varying degrees of struggle, fear, loneliness, despair, and other difficulties. The challenge and correlation of different forces, such as life and death, power and desire, good and evil, have become a daily concern for people. During the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine, I created the “Mayfly Diary” and “Light” series. The former takes the form of a diary, using paper-based materials and collage techniques to express various feelings and associations. In these works, I emphasize non-linear narrative, time and space reset, and fragment collage. I also find inspiration in late Middle Ages and early Renaissance painting. These works convey the difficulties and absurd feelings of existence. The themes are derived from familiar objects, character studies, everyday imagery, etc.

How do you navigate the intersection of the personal and the political in your art?

People living in China will feel that their personal life (including growth, education, job seeking, social status, etc.) is closely related to “politics.” This is an objective social reality, but it does not mean everyone will be interested in politics or pursue political careers. My work explores the relationship between individuals and society from an artistic perspective, examining the impact of society on human nature in changing times. I am not interested in political science. Of course, I am not an artist specializing in the study of visual language, which means art is a medium that obeys the human heart. The core of art is a form of spiritual perception, containing an individual’s inner experience of life and human nature, knowledge, concepts, and technology.

Some critics have pointed out that your work reflects a sense of longing or nostalgia. Can you elaborate on these emotions and how they manifest in your art?

The subject matter of my works often originates from the past tense, which first stems from my inability to find a genuine sense of popular symbols. Materials or sources are often extremely important for a painter, especially for a painter who enjoys figurative representation. I often spend a lot of time browsing through various materials, which offer different imagery, experiences, and understandings of life in different periods. Interestingly, most of the materials I collected on impulse were from the past, such as everyday objects, familiar scenery, and so on. Perhaps this is a subconscious aesthetic preference. However, this does not mean that I am an artist who hopes to “reminisce” through my works. “Memory” is just an idea. It contains a particular understanding and perception of time. The “temporality” in works is very important to me, as it strengthens our understanding and imagination of mental space. As a result, I am unable to present a certain sense of “immediacy” in my works; this is an attribute that I learned in classical art.

Let’s discuss your use of found imagery. What criteria do you use to select your imagery, and what do they represent to you in your paintings?

The imagery in my works is primarily based on my personal history including family photos, everyday items, newspaper and magazine clippings, and movie screenshots that resonate with me. When selecting them, I evaluate their ability to evoke visual imagination and emotional significance. However, I transform these materials into some kind of unfamiliar symbol and reorient their original physical and historical significance. In my recent creations, I fuse the symbolic relationships between these subjects and objects, creating a kind of “abnormal” combination between them by including different proportions, perspectives, etc. This results in a more psychologically distinctive combination of nonphysical relationships. In recent paper works, I perform hand tearing, carving, and collage to achieve a multi-layered spatial overlay effect of particular images. This fragmented, torn, multi-layered, but unified visual processing responds to contemporary life experiences. I will not rule out the influence of traditional art on my artistic language, because I do not define myself within the realm of experimental art. I am interested in finding the connection between traditional art and contemporary life. I derive a different kind of excitement from classical art, both visually and emotionally. In this sense, I may be a “classicist.” This is my understanding of contemporary art: it can be fragmented, breaking boundaries, or searching for connections with the past in contemporary contexts. The so-called regression is also a kind of forward movement, and looking back is often a response to the present.

Your work often features isolated figures. How do you approach the concept of solitude and isolation in your art?

The existence of one person often implies the existence of a group of people. The history of art teaches me that artists always shift from personal to universal experiences. When personal experience reaches a particular level, it then transforms into some kind of common experience and enters a system of knowledge. Individuals and the general public are always relative and connected. A focused artist is lonely, but their artistic results are often public. When I focus on drawing a Chinese-style family portrait, I hope it conveys a universal message rather than the story of a particular family.

My “Bloodline-Big Family” series is related to my personal family experience, as well as my college studies in Chongqing. When I read Gabriel García Márquez’s A Hundred Years of Solitude, I found that it was related to the history of Magondo described in the book. This made me realize that when describing my personal experience, I should delve deeper into universal meaning.

All images courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista