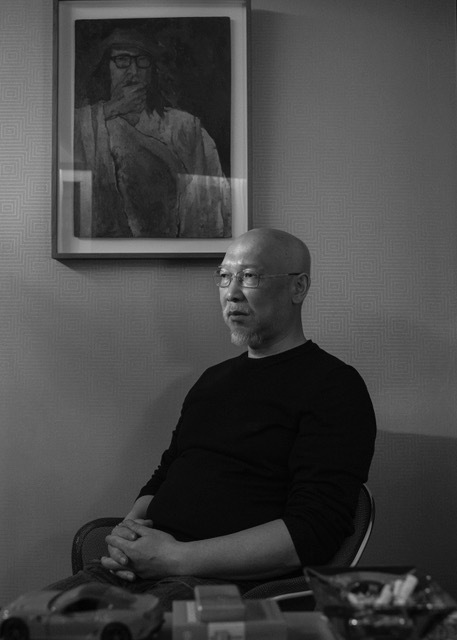

Zhang Enli’s artistic vision transcends the mundane, elevating everyday objects into profound meditations on existence itself. Born in 1965 in Jilin Province, China, Enli’s journey as an artist is a testament to his relentless exploration of the subtle nuances of the world around him. Currently based in Shanghai, his work resonates with viewers worldwide, offering glimpses into the depths of human experience.

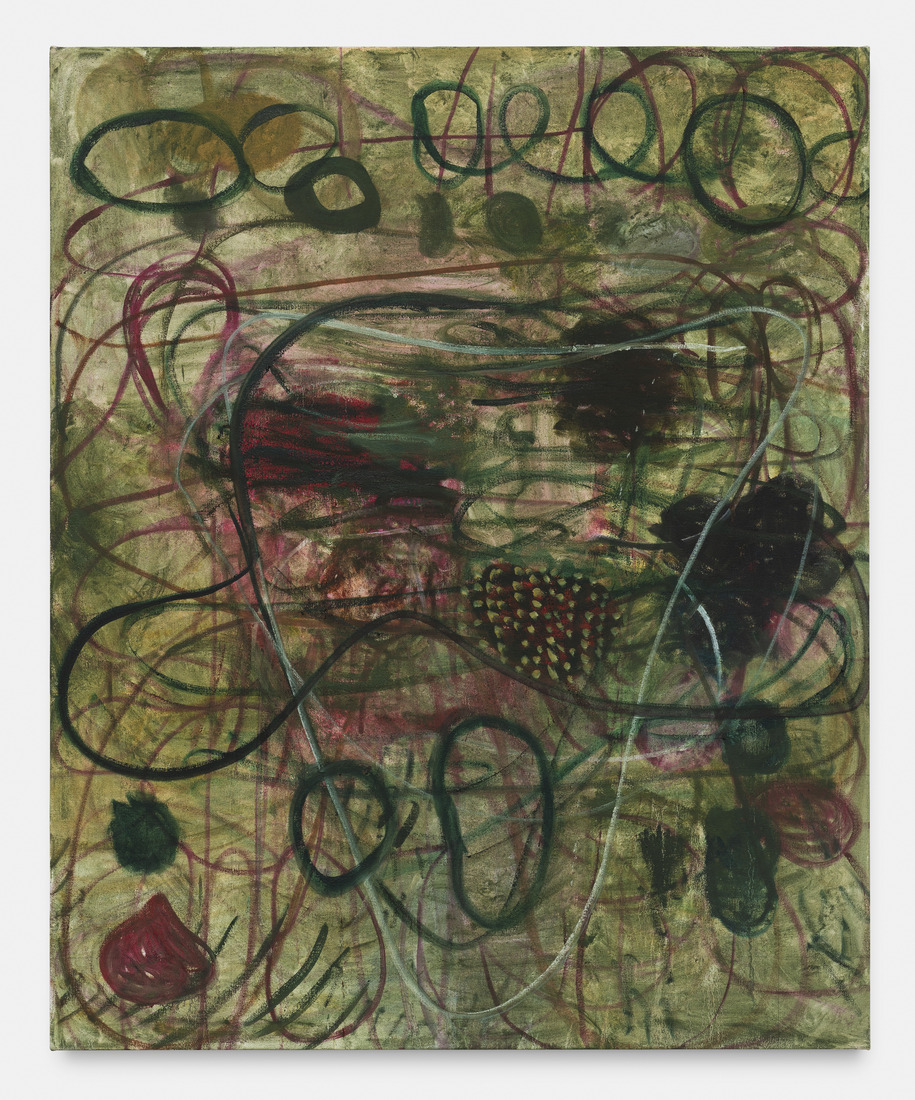

Enli’s oeuvre is characterized by a profound sensitivity to the ordinary. He meticulously selects subjects that might easily go unnoticed—a discarded piece of string, a weathered hose, or a solitary marble ball. Yet, in his hands, these objects undergo a metamorphosis, transcending their materiality to become vessels of deeper meaning and contemplation.

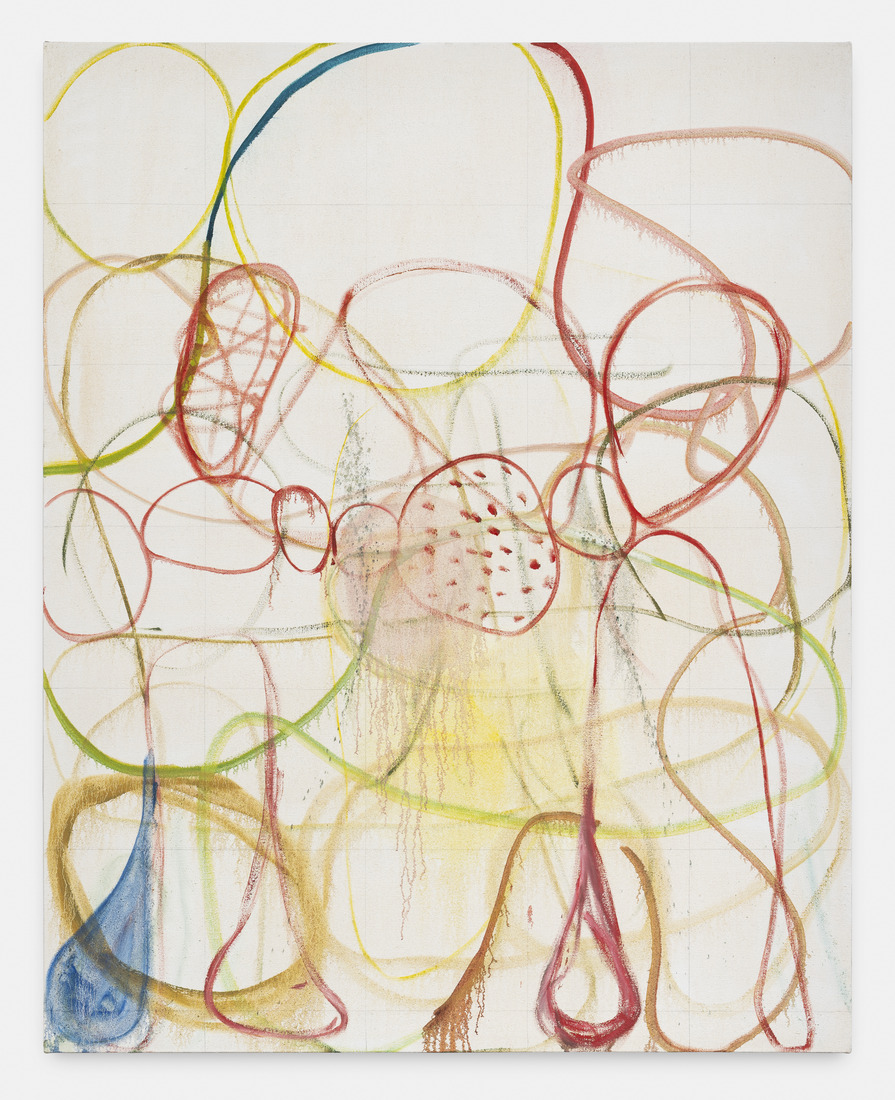

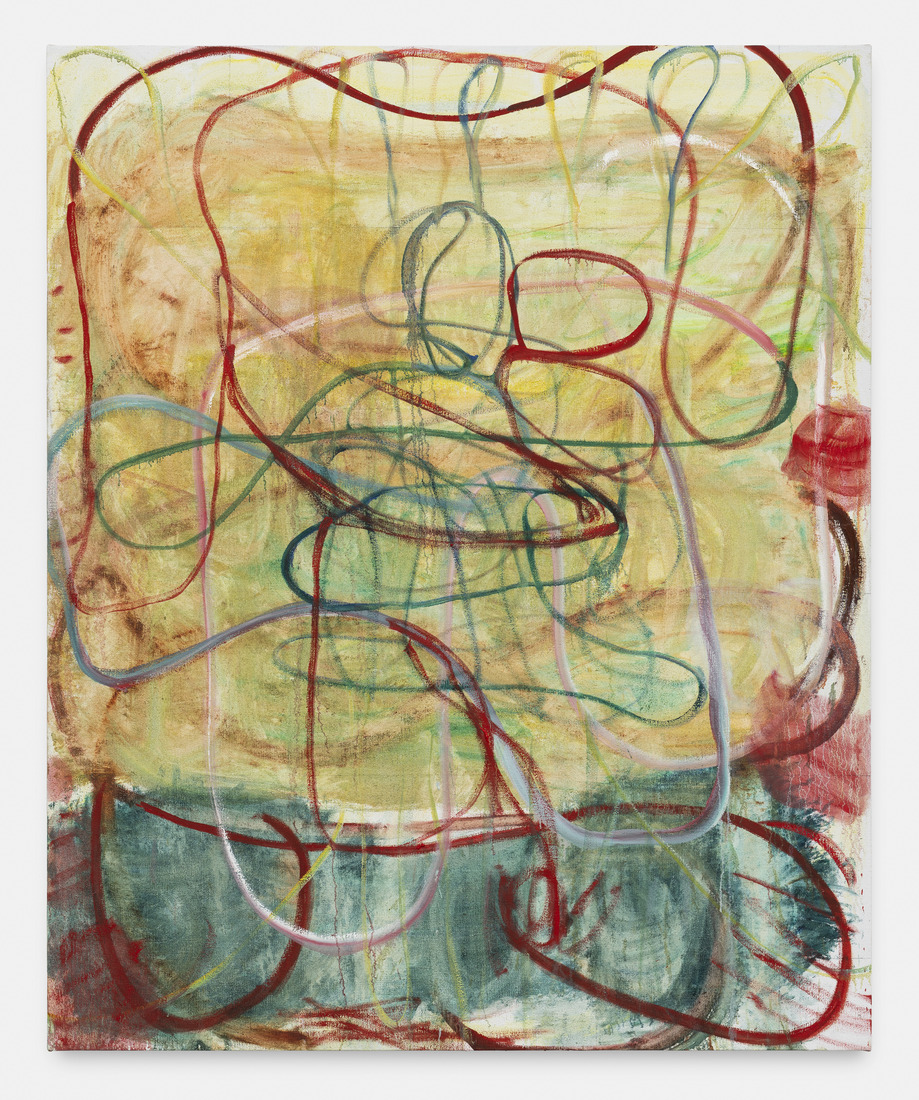

In his figurative works, Enli employs skewed perspectives and expressive lines to imbue his subjects with a sense of drama and significance. Drawing inspiration from traditional Chinese brush painting, his artistry is underscored by meticulously drawn grids that provide structure amidst the fluidity of his brushstrokes. Through muted tones and loose washes of paint, Enli creates a liminal reality where only the essence of the object is laid bare, inviting viewers to delve into the profound simplicity of his compositions.

Not content with conventional confines, Enli’s foray into installation art, particularly his renowned Space Paintings series, marks a departure from traditional canvas-bound works. By painting directly onto the walls of a room, he crafts immersive environments that evoke nostalgia and introspection. Whether abstract or figurative, these installations transcend mere visual representation, compelling viewers to inhabit the artist’s emotional landscape and retrace the footsteps of his creative journey.

In his most recent paintings, Enli delves even deeper into the realm of abstraction, seeking to capture the essence of his subjects rather than their physical form. Each stroke on the canvas becomes a conduit for his personal reflections and recollections, blurring the lines between reality and imagination. As Enli himself reflects, “Sometimes, the obscured object also creates a trace with the passing of time… it is visible yet invisible.”

With each brushstroke, Zhang Enli invites us to peer beyond the surface of the ordinary, urging us to discover the extraordinary within the seemingly mundane. His artistry serves as a poignant reminder of the beauty that lies in the everyday, and the profound truths that await those willing to pause and observe.

An Interview with Zhang Enli

By Carol Real

Zhang Enli, your recent abstract paintings are inspired by ordinary objects and the traces they leave over time. Can you share a specific moment or object that profoundly impacted your art?

Instead of focusing on a specific moment or an object, my work relates to life changes and life itself. My earlier works from the 1990s to 2000s dealt with questions about life, e.g. survival. However, my newer series is an abstract series that stems from the idea that everything is a portrait, embracing a more expansive perspective. I find a sense of liberation in this notion of portraits. While a portrait has been an identifiable and distinct form in art history, I aim to challenge the boundaries of portraiture and redefine its historical context, thus finding my own sense of liberation within it. I believe portraiture can encompass everything from a chair to a table, transcending its traditional definition.

How do your site-specific installations, such as Space Painting, alter the viewer’s encounter with your art, leading to a shift in their experience and perception within immersive environments?

When working on my installations, I do not necessarily intend to convey a particular meaning but rather to create a thought-provoking yet enjoyable experience for the viewers. While my installations might look like a simple game, upon entering, viewers experience something positive and joyful, perhaps reminiscent of their childhood memories. I aspire for art to evoke simplicity and pleasure.

In the past, I made an installation from 3,000 cardboard boxes, reaching 4 meters high. Constructed from cardboard boxes and tape, it resembled a castle and formed a maze-like structure where visitors could become lost. The sheer magnitude of the installation also instilled a sense of awe.

You mention that your style draws from both Eastern and Western painterly traditions. How do these different traditions influence your creative process, and do you see any harmonious intersections between them?

My understanding of lines is deeply rooted in Eastern traditions, tracing back to my childhood. Simultaneously, I draw inspiration from Western paintings, particularly in observing the intricate use of lines by European artists such as Hans Holbein and Leonardo da Vinci. For instance, the lines in my abstract pieces are influenced by both Eastern and Western traditions, synthesizing these influences.

Regarding differences, discussions often revolve around distinctions between Eastern and Western traditions. However, the true disparity lies not in tradition per se, but in the nuances, specifically in the lines. For example, in da Vinci’s drawings, the black color emerges from intricate details, initially consisting of hundreds of lines he drew. This is parallel to how Chinese paintings approach variations in details with simple colors.

Furthermore, Asian artists in my generation tend to have a strong idea of what is “Eastern” or “Asian.” Nevertheless, I anticipate that this emphasis will diminish in significance over time, while details will remain paramount. Across cultures, there are identifiable elements that distinguish them, but I believe the significance of such distinctions will gradually diminish.

The use of color and light in your work is distinctive and highly regarded. Could you elaborate on your preference for thin washes of paint and clear, crystalline colors, and how they contribute to the emotional impact of your work?

A good artist should be mindful of how one uses paint as a form of respect toward the material. For instance, if you examine ancient murals in China or pre-Renaissance Europe, you’ll notice they utilize thin washes of paint, avoiding overuse. This practice reflects a reverence for the material.

Using thin paint may not entirely cover the canvas, in contrast to the very nature of oil paint. However, I appreciate the opportunity to witness the evolution and layers of paint on the canvas—it reveals the process, the grid, and the history. This approach introduces a new painterly language, allowing viewers to observe the journey from beginning to end, including everything in between. Of course, “mistakes” also become integrated into the work.

Your quote about using the outside world as a mirror to document contemporary life is intriguing. How do you select the aspects of contemporary life that you feel compelled to document through your art?

An artist should be able to manifest and define the era one is living in. An artist needs to feel and capture essential sentiments and ideas of an era. If you look at the works of Edward Hopper, for instance, you can sense the zeitgeist of the time as his works truly captured the essence of America’s industrial urbanism.

How does the concept of time shape your artistic decisions and the stories you convey, given that your art frequently captures the passage of time and its enduring imprints?

Time is difficult and perhaps the most difficult part is erasing its trace. To ensure a work remains relevant through time, in history, one must transcend temporal boundaries. It involves capturing something that transcends time itself, aiming to document the timeless.

Your works are renowned for their fluid and gestural style. How do you achieve a sense of spontaneity in your paintings while maintaining a structured approach to your craft?

When you look at a work by Willem De Kooning, you can immediately identify it as his while he maintains his spontaneity and playfulness. I think that’s what makes a great artist. I also think you are born with the ability to paint with this flow and spontaneity. It’s not about a structure or design, which can be replicated easily. Rather, it’s the reflections of an artist’s emotions and thoughts that can’t be reproduced effortlessly.

Could you provide insights into the central themes or concepts that are explored in your forthcoming solo exhibition in Brussels? Moreover, in what ways could these themes or concepts differ from those explored in your previous exhibitions?

The body of work featured in my exhibition at Xavier Hufkens is a new series that started five to six years ago, marking a significant new phase in my artistic journey. This phase began with my idea that everything is a portrait, which is now central to my practice. Also, it served as the theme of my recent solo exhibition, Zhang Enli: Expression at the Long Museum in Shanghai last year.

All images courtesy of the artist and Xavier Hufkens. All photos: HV-Studio.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

More images: