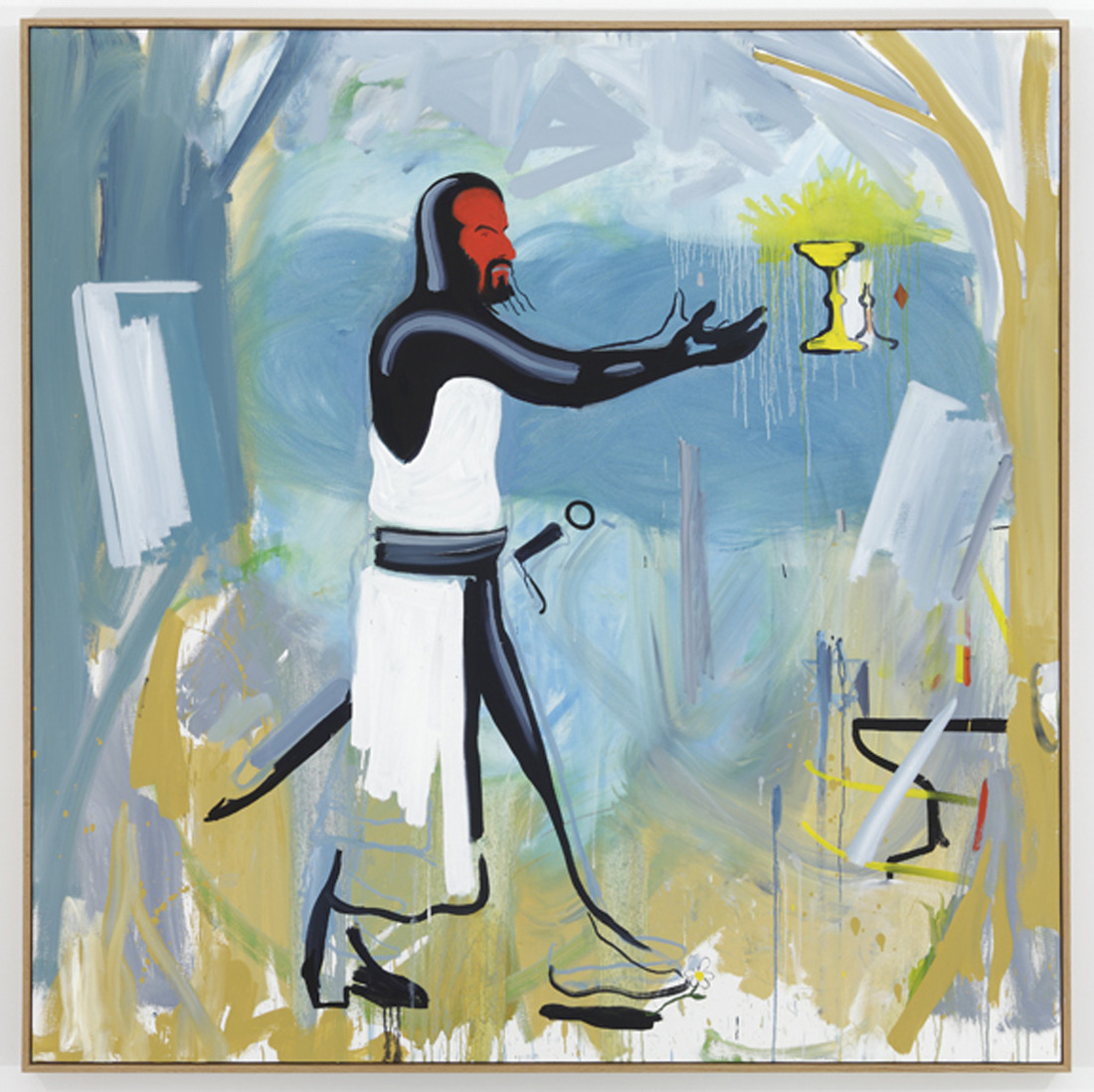

Renowned for his infectious exuberance and raw materiality across paintings, drawings, and collages, Spencer Sweeney is a multifaceted artist, musician, and cultural provocateur based in New York City. Born in 1973 in Philadelphia, he graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1997 before establishing himself as a vital force in the city’s art, nightlife, and music scenes.

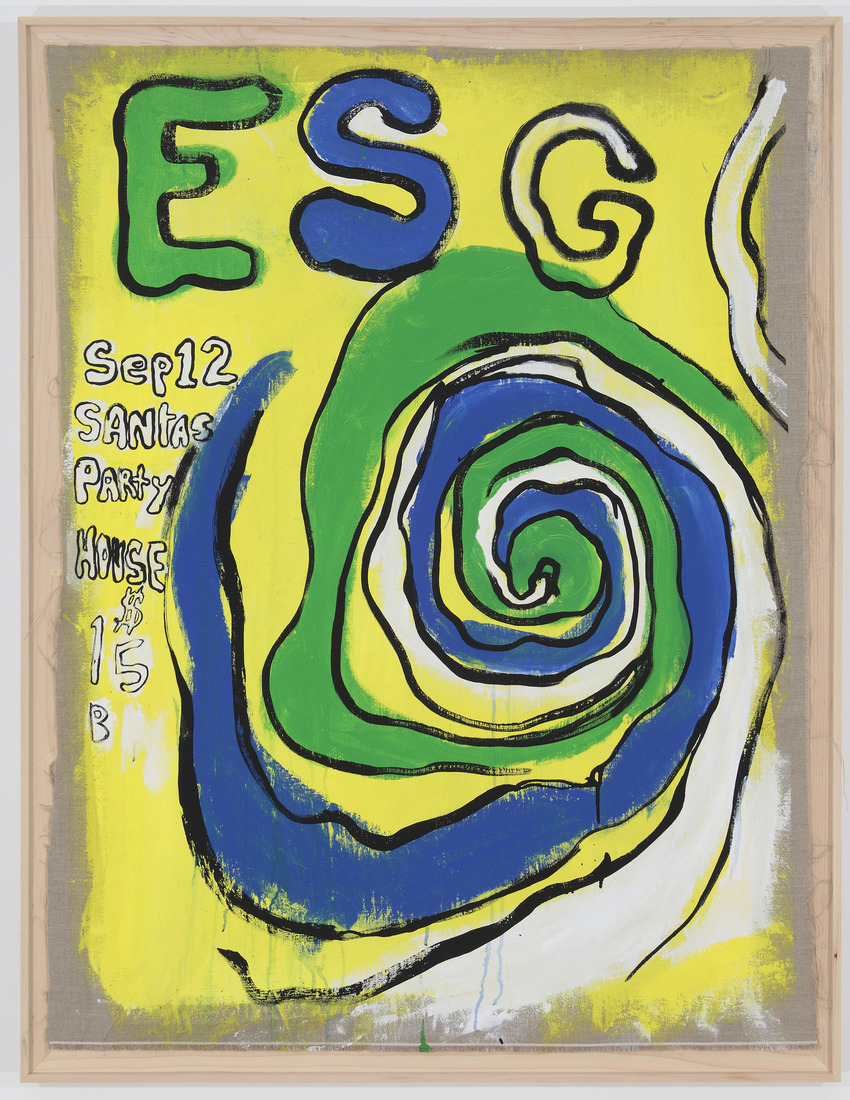

Sweeney’s artistic journey is a dynamic exploration of various mediums, marked by a hardcore ethic that challenges traditional norms. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, he emerged as a pivotal figure, not only as an artist but also as a musician, DJ, and owner of the iconic nightclub Santos Party House. His versatility spans visual art, music, and performance, embodying the spirit of a ‘Downtown Renaissance’ artist in the new era of New York.

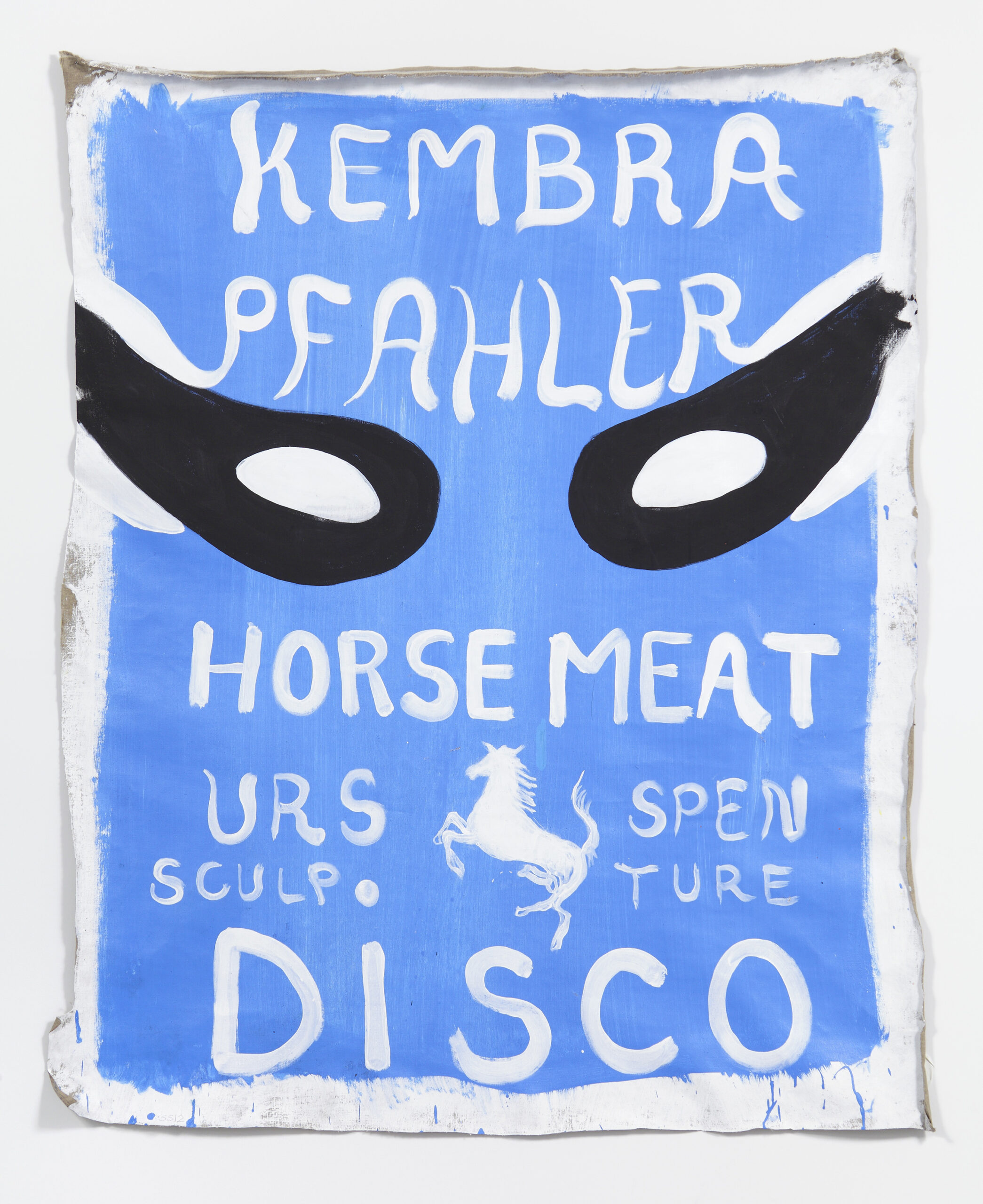

Collaboration is at the core of Sweeney’s practice. His collaborations with fellow artists—such as Kembra Pfahler, Peter Doig, Korakrit Arunanondchai, and Urs Fischer—often debuted at his nightclub Santos, bringing the energy of nightlife into his creative process. This collaborative ethos extends to his exhibitions, where unusual and informal displays challenge traditional gallery spaces, creating a vital energy for his work.

Sweeney’s psychologically rich figurative paintings defy easy categorization. The artist’s ability to seamlessly shift styles and draw from vastly different references adds to the dynamic nature of his work.

In 2015, a 500-page book titled “Spencer Sweeney” was published, capturing conversations between the artist and inspirations from cinema, literature, music, New York nightlife, and contemporary art. The book reflects Sweeney’s fundamental investment in context and open exchange.

Continuing to push boundaries, Sweeney’s painting and drawing salon, Headz—a collaboration with Urs Fischer and Brendan Dugan—hosts performances by experimental jazz musicians and has received international acclaim in cities like Berlin, Mexico City, and Paris.

Spencer Sweeney’s impact extends beyond the canvas, influencing the cultural landscape of New York City for over two decades. With exhibitions at esteemed institutions like MoMA PS1 and the Whitney Biennial, representation by prestigious galleries, and a commitment to constant innovation, Sweeney remains a dynamic force in the contemporary art world.

An Interview with Spencer Sweeney

By Carol Real

As a prominent figure in the Downtown Renaissance of New York, how do you navigate the intersections between visual art, music, and performance in your versatile practice? How has your multifaceted approach contributed to the evolving cultural landscape of the city?

The social leg of any creative community is an important thing to look after. The idea of starting a nightclub greatly facilitated this kind of social structure for the creative community, specifically in New York City, Brooklyn, and the neighboring boroughs. The social aspect has to be present in a creative community. That’s where a lot of cross-pollination, exchange of ideas, and the synthesis of new ideas occur. That was very significant to me. At one point, I decided to take it into my own hands to create such an environment. That became the project of the nightclub, which was a challenging experience of being involved in the ownership of a nightclub. I had already been working as a visual artist for a while beforehand. At one point, it was an idea that I had cooked up with my friend Andrew W.K., a performer and an artist in his own right. Once the idea was born, there was no turning back. We started on it probably in 2006 and then were able to open the nightclub around 2009. Action and social activity in real-time from person to person are important parts of life and creative expression.

However, before the nightclub idea happened, I started collaborating with some friends in 1998 to form a performance art group, and we called it Actress. My collaborators were Lizzi Bougatsos, Sadie Laska, Amy Gartrell (who are now working in visual arts, painting, sculpture, and installation), Jess Holzworth, and Hilary Small. So, we all started this band; it was kind of a conceptual art damage noise band. It had several different aspects where we were creating props to interact with during our performances. The announcements for the performances became this kind of multi-pronged multimedia art project. That was part of creating this performance and action in real life and real-time while bringing that into the gallery scene in New York City. At first, we only performed at galleries; that was part of our decision of where to put our energy. It felt like we were filling a void, and that was part of the motivation to initiate and create it. That became the meeting point between the art world, the world of visual arts, and that of performance and social activity.

How has your experience as a drummer shaped or influenced your approach to visual art?

I grew up in a musical family, and I’ve played drums, guitar, and some piano since I was a child. I would tour with bands playing drums. I did many tours with Will Oldham or Bonnie “Prince” Billy, playing drums. In the group, Actress, I played a lot of drums too. Sometimes I play with this band called IUD, which includes Lizzi Bougatsos and Sadie, who were both part of Actress. We still play, and I’ll play drums or guitar in that too.

Your work spans various mediums, including painting, drawing, collage, and performance. Do you have any preference among these mediums?

I have no preference; it all calls upon the same sensitivities and headspace to create, whether it’s painting, playing music, composing music, writing, or cooking. I see similar decision-making processes across these different forms of expression. To me, there’s no favorite, just a continuum.

Can you elaborate on how your multimedia environments, transforming gallery spaces into open workshops and performance stages, expose the private world of the artist’s studio to the public?

The Actress project often took place in gallery spaces. Then, there was one particular project I did with Gavin Brown at his gallery. It was a more rigorous endeavor where I lived in the space and brought the studio into Gavin’s gallery. Additionally, I started working on a piece of amateur experimental theater akin to a rock opera. Thus, the space became a theater workshop as well as a studio for painting, sculpture, and other activities. At the end of the month-and-a-half-long project, we presented the rock opera that we had been working on along with the collaborators. We had a good crew, including Kembra Pfahler and Danny McDonald, who helped write the script. Danny also performed and is a great visual artist. He served as the narrator for the opera. Additionally, the bands TV Baby and Endless Boogie, and the choreographer Maria Hassabi were part of the crew. While I’m omitting some people, these were four important parts of the performance and its participants.

Could you delve into how collaboration has influenced your practice, from forming relationships at your nightclub to experimenting with them in gallery spaces? How does this enhance the energy of your work?

There are different facets of my work, some of which involve community, some involve collaboration, and some are solitary. One project that opened up and became more of a communal experiment was the Headz project, where I opened my studio every Sunday night for nine months. During that time, there was live improvisational music, painting, and drawing with materials available for everyone. Being open to the public took the whole collaborative experience to the next level. I collaborated on that with Urs Fischer and Brendan Dugan from Karma Gallery. We all pitched in to make that happen, and it turned into something spectacular. We published a set of 18 books of all the artwork that happened there including photo documentation of the interior and the music. It was a great thing. All of these major jazz players started showing up to play because it was an environment where you could play truly improvisational music. So, all these major players such as Daniel Carter, Wallace Roney, Craig Harris, and Al MacDowell, participated. It just grew into this wild thing, and the place was covered floor to ceiling with artwork. When I look back at it, I wonder, “Wow, how the hell did that happen?” That was another form of collaboration. The improvisational music and art-making party was called Headz. I have just set up an archive. We’ve gathered all of these images, and we’re starting to post them regularly on Instagram. In the spring, I think we’ll host an event where we invite the participants and then distribute the books.

How does your 500-page book of conversations, published in 2015, demonstrate your deep interest in context and open dialogue, drawing inspiration from cinema, literature, music, and contemporary art?

It is a combination of reproductions of my artworks and recorded conversations with a real mix of artists, musicians, actors, and others. I didn’t set out to formally make a catalogue raisonne, but it turned out that way. Since I came across the first painting I ever made and a drawing of some early works, it is organized chronologically. It seemed interesting and logical to include recorded conversations with people whose work I admired or thought would be intriguing to talk to, and might reveal fascinating ideas and stories. Some of the people interviewed in the book are Glenn O’Brien, who had the great project TV Party, which I was greatly inspired by. The whole social leg of the work TV Party, which was a public access show in New York City from the late seventies through the early eighties, was Glenn O’Brien’s creation. Once a week, they would take over this public access TV studio, attracting notable artists and creative figures from downtown such as Debbie Harry and Jean-Michel Basquiat. I’d seen some of that footage while in art school, and that inspired me to move to New York City, get involved, and create projects that echoed the kind of activity that Glenn was engaged in. Talking about the people whom I interviewed, there are some other interviews with Natasha Lyonne, Abel Ferrara, Nona Hendryx, Jennifer Herrema, Harmony Korine, and lots of other good people.

What qualities do you consider when you truly admire someone’s work or career, or when you use them as an inspiration?

It’s more about the existing qualities that somebody may have, and then how I react to them. So, it varies greatly case by case, and I can’t say, “I like this about people, and I like that about people.” It’s more like people do what they do, and I either appreciate it or not. There are things that I’m attracted to. I follow and observe certain qualities or aspects of people’s work or ideas, and I find myself drawn to some things that resonate with me.

Could you elaborate on the influences of jazz and popular culture in your work, and how they are reflected in your paintings, drawings, and collages?

It happened a long time ago. I found a watercolor painting from when I was a young child, and it depicted the word “jazz” with a fellow below it playing a trombone. Maybe it all started there. I listened to music, and somehow, all about messaging, painting, and creating pictures. When I was young, a big part of my inspiration was the punk rock flyers announcing punk rock shows around Philadelphia. Artists like Raymond Pettibon and Pushead were making art for punk bands to promote concerts and performances. I started collecting these flyers from street light posts, bulletin boards at universities, and wherever I saw them around the city. I was always drawing and painting for as long as I could remember. At some point, a promoter, a fellow who was organizing punk rock shows in downtown Philadelphia, asked me if I would like to start drawing some flyers and advertisements. I got involved in that. Then, when I opened the nightclub, I started doing paintings to announce the parties and the different performances, including musical performances. Musicians and people playing music have consistently been the subjects of my paintings and drawings. It relates in many ways. For me, I see the sensitivities that you use when painting, drawing, or organizing a visual composition as being synonymous with the sensitivities used when playing music or writing a piece of music. Often when I’m painting and working through a composition, trying to make a picture work, I treat it like a piece of music. You need different qualities of mark-making to express different activities, frequencies, and energies. When you gather an array of different marks and can explain the scenario to your satisfaction, feeling that you’ve sufficiently captured the diversity of life, you can present it. It’s like Beethoven. Beethoven has created an entire universe in each of his musical pieces, where an entire universe is explained, in all of its complexity down to the atom. I feel that music, painting, drawing, or any type of visual art pretty much works in the same way and calls upon very similar sensitivities.

Could you discuss the role of improvisation in your performances, particularly those featuring experimental jazz musicians?

Improvisation is a very important concept to me and something that I continuously explore. The Actress project took improvisation to an extreme because it differs; you can improvise alone in the studio. That requires a certain amount of courage and strength, to improvise in a room full of people with absolutely zero scripting. This idea of improvisation is so important that even the greatest failure you can imagine is justified because of the value and significance of the act of improvisation; it’s like the unknown outcome. When I’m painting, I try to find ways to remove my hand and decision-making process from the work. However, it becomes a delicate balance because you want to spend time in these dark waters of the unknown, into this black void. Inevitably, you’re going to step outside to organize and orchestrate things. It’s like a weird dichotomy where you are constantly dipping into the loss of control and then wrangling it in, regaining control, and then losing it again. It’s this weird cycle.

How do you approach the portrayal of psychological themes in your work, and what draws you to explore these aspects?

I’m interested in the human experience, particularly in the various emotional and psychological landscapes that human beings inhabit. I might work in a portrait format, perhaps painting a face or head, or sometimes in self-portraits where I don’t have a plan. I dive into a face, and it might start with a texture, color field, line, or shape. I’m trying to create these different ways of expressing emotional or psychological states that our physical existence may not allow us to articulate fully. I seek new ways to express various emotional and psychological states by rendering these faces.

“Availablism” is a term closely associated with your work. How do you interpret this concept in the context of your art-making process?

That’s an idea from Kembra Pfahler, the great performance artist who created the voluptuous horror of Karen Black. She created that word and introduced me to the whole concept. After Kembra had turned me on to it, I started seeing that there were a lot of parallels and different ideas of availability in different approaches to my work. Then, the most literal sense was my series of self-portraits. That is a very obvious approach because what you have available to you at all times is yourself.

How does your art capture a casual yet rebellious spirit in portraiture, and how do you keep the tradition of painting alive while breaking the rules?

Not all of the time, but a significant amount of innovation in any field is achieved through breaking the existing rules and norms and taking chances. It becomes this back-and-forth between knowing history and understanding the existing processes. Breaking down the rules is the way that innovation happens or the synthesis of new approaches emerges. You are going back to what’s happened and to what you’ve learned throughout your experience within a given medium. Then comes the time to destroy that and see where that leads as a creation. Breaking rules or destroying something can be the starting point of creation.

All images courtesy of the artist.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista