Sir David Adjaye OM OBE is an award winning Ghanaian-British architect known to infuse his artistic sensibilities and ethos for community-driven projects. His ingenious use of materials, bespoke designs and visionary sensibilities have set him apart as one of the leading architects of his generation. In 2000, David founded his own practice, Adjaye Associates, which today operates globally, with studios in Accra, London, and New York taking on projects that span the globe. The firm’s work ranges from private houses, bespoke furniture collections, product design, exhibitions, and temporary pavilions to major arts centers, civic buildings, and master plans. His largest project to date, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, DC opened on the National Mall in Washington DC in 2016 and was named Cultural Event of the Year by The New York Times.

In 2017, Adjaye was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II and was recognized as one of the 100 most influential people of the year by TIME Magazine. Adjaye is also a recipient of the 2021 RIBA Royal Gold Medal, considered one of the highest honors in British architecture for significant contributions to the field internationally. In 2022, Adjaye was appointed to the Order of Merit, selected by Her Majesty the Queen, in recognition of distinguished service in his field. He is also the recipient of the World Economic Forum’s 27th Annual Crystal Award, which recognizes his “leadership in serving communities, cities and the environment”.

As a young boy born in 1966 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Adjaye’s childhood saw stability in movement as his father Affram was a diplomat whose work took the family all over the world to places such as Kampala, Nairobi, Cairo, Beirut, Accra, and Jeddah. Adjaye was born into a vibrant era of hope where just previously Kwame Nkrumah had won the country independence from the British in 1957 and the spirit of emancipation was one that influenced the family’s mobilities. In his early adulthood, one of the many prolific projects that evolved out of David’s travels is the ‘Adjaye Africa Architecture: A Photographic Survey of Metropolitan Architecture’. The project took place over a ten year period documenting fifty-four major African cities and showcasing a concise urban history, fact file, maps and satellite imagery that come together in a rigorous analysis and reconceptualization of what African architecture is and can truly be.

A formative moment in Adjaye’s childhood was when he realized the inequities that his brother Emmanuel – who was partially paralyzed — faced when visiting his specialized school. Adjaye noted how inefficient, run-down and degrading the actual facility was. During his university education at South Bank he began to think about designing a facility that would provide better care for the handicapped, a moment he describes as changing everything. He came to the understanding that architecture should serve people and as a prevalent force within all our lives it too should take to the realm of egalitarianism.

Bio courtesy of Adjaye Associates.

An Interview with Sir David Frank Adjaye

By Carol Real

Your background encompasses Ghanaian and British heritage. How does your dual identity influence your approach to architecture, and how do you navigate the complexities of cultural identity in your work?

For me, the complexities of cultural identity, as people describe it, are simply the way I operate. I don’t know any other way. I’m constantly negotiating between these influences. I was born in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania before moving to London, and my work there allows me to engage with both cultures.

It ties back to my politics and the principles of architecture are deeply intertwined. I use my background as a foundation for my creativity, and it extends to all aspects of my work, including in the USA.

Much of your work engages with history and memory. In your view, what role does architecture play in shaping collective memory and identity

I think architecture, apart from making beautiful forms, is, for me, another script—a script of civilization. It speaks to how and what we are doing and what we are saying about our civilization at any given time. So, every time we build, there’s a conscious moment to signify what we’re expressing about our society.

For me, history, place, and memory are such powerful narratives, that language, and the way we communicate are not just about our interaction with architecture, but also about our exchange with the environment, how we see ourselves in the world, and what we envision for the future, for future generations. I often say architecture is, in a way, a codification of all the stories we want to tell the future.

Architecture can be a powerful tool for social change. Are there specific projects where you’ve seen your work impact communities in unexpected ways?

At Adjaye Associates, I work to always act as an enabling agent within undervalued or underappreciated scenarios. I’m most inspired by the places where architecture plays an edifying, uplifting role while also providing a service. Many projects come to mind. One that stands out is Sugar Hill in Harlem. Building this housing project gave me immense joy. Seeing homeless people wanting to live in these homes, witnessing the community that formed there, and knowing that these facilities transformed a place of scarcity into something generous for them was incredibly fulfilling.

On the formal end, there’s the Studio Museum, which Adjaye Associates is currently completing, and before that, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Building on the National Mall was a powerful moment, but also one that came with a huge responsibility. After its completion, it was extraordinary seeing the community feel like they finally belonged in a place where they previously felt excluded. People expressed pride in being American, in being part of the American story, and in their roots in Africa as well as the diaspora. It felt like I was able to bridge something profound.

Beyond the excellence of the architecture itself, what’s important to me is the ability of the building to become part of the stories of the people who experience it. Whether it’s a mother telling her daughter or son about something, or a father reflecting on his past or imagining a future, that’s where architecture, at its best, excels. It’s a form of art.

The work you create often blurs the lines between art and architecture. How do you strike a balance between functionality and aesthetics in your designs?

It’s a deeply personal process for me, not just from a work standpoint, but from a perspective that goes beyond the functional aspect of architecture. The toughest question I face is, “What is it?” This question is central to architecture because while the function, program, and client requests can provide answers, the real challenge is understanding why it exists in a particular form. Addressing that question early in the design process is crucial.

For me, that’s where the art of architecture emerges. Yes, you solve the problem, but there’s something deeper that comes with this immense responsibility.

Your designs often challenge conventional notions of space and form. How do you balance innovation with functionality and materials in your architectural concepts?

I’m currently obsessed with new materiality. Right now, I find myself drawn to returning to the earth. In the 20th century, the world became preoccupied with mechanization, tools, and assembling things. Now, I’m very focused on re-engaging with the earth. The earth is the most abundant material on the planet—more abundant than anything else. We often select marbles and rare materials, but the earth’s most plentiful resource, soil, is something we almost overlook.

For me, my practice is now centered on exploring the nature of soils across different geographies and contexts. How do we think about the relationship between our work and the soil? This is the ultimate innovation for me right now. It’s not about the mechanization of industry but reclaiming our connection to the planet through the use of its most abundant material to address one of humanity’s most essential activities—building.

Do you have any favorite materials or textures that you love?

I love earth. It’s really that simple. I’m fascinated by the possibilities of working with it—ramming it, compressing it, stretching it, folding it. I’m just obsessed with it.

Sustainability has become a critical aspect of modern architecture. How do you integrate sustainable design principles into your projects while maintaining your distinctive aesthetic and considering future challenges in architecture?

For me, sustainability is not something you address after everything else; it’s not just about choosing the right energy efficiency measures or formal elements. Those are important, but sustainability is a mindset. It’s a way of thinking about everything—from the social, cultural, and historical context to the energy, material, and planetary context.

Sustainability, for any architect who respects the privilege of creating architecture, involves understanding this holistic system. Without it, you’re not fully embracing the responsibility of making architecture. You need to be able to look at your work and say, “With the resources I was given, I’ve done the best I could.” It’s not about the market; it’s about considering the entire life cycle of a project. I place this responsibility on my team and myself.

Apart from my authorial work, my office includes a large team of researchers—social scientists, gender specialists, political scientists, and sometimes even journalists. I find these perspectives fascinating because they bring a wealth of information that architects don’t typically access. When people visit my studio, they’re often surprised by the diversity of thinkers we engage with. Before I start designing, I always listen to these experts to understand how they view the information. Then we begin a dialogue and discuss how architecture can respond to these perspectives. It’s a long way of talking about sustainability, but it’s all intertwined.

Once you become skilled at your craft, there’s a temptation to simply keep doing what you’re good at. However, that’s not enough. I always ask, “Why are we making this? What is it doing? What information do we need to ensure we’re doing the right thing?”

What are the challenges you encounter most often in your work?

Not enough time. There’s never enough time. Occasionally, there’s time, and that’s beautiful, but often we’re innovating and pushing boundaries. We’re always asking contractors and the construction team to learn things they may not be familiar with. They usually want to stick to what they know, complete the job, and move on with a profit. Meanwhile, we want to try out new ideas and test things.

So we end up driving everyone crazy. At first, they’re frustrated, but by the end of the project, they say, “We love this project.” I go through this cycle every time: at first, I think, “Oh no, here we go, they hate me.” And by the end, they’re saying, “Look at what we achieved,” and “I’m so proud.” I know they’ll tell others how much they enjoyed the process in retrospect, and I’m always glad we’ve shared the experience.

In a way, each project is an evolution of the lessons learned. You get better as you get older—one of the few benefits.

The National Museum of African American History is a landmark project in your career. How did you navigate the complex task of representing such a rich and diverse history through architecture?

Listening. Listening without judgment, being open to the information from both experts and people on the ground, and hearing their stories. Working on this project was as much an education for me as it was a professional endeavor. I have strong opinions about it, but I also learned so much in the process. That, for me, is part of the joy of architecture—when you get it right, it’s transformative. I often think about actors who say, “I took that role, and it taught me so much.” I feel like architecture is similar. You may enter a new country, context, or community with a wealth of skills, but if you truly listen, those experiences expand you. So, it wasn’t complicated; it was a joy to be the vessel, the lens through which these stories were channeled and transformed into this building.

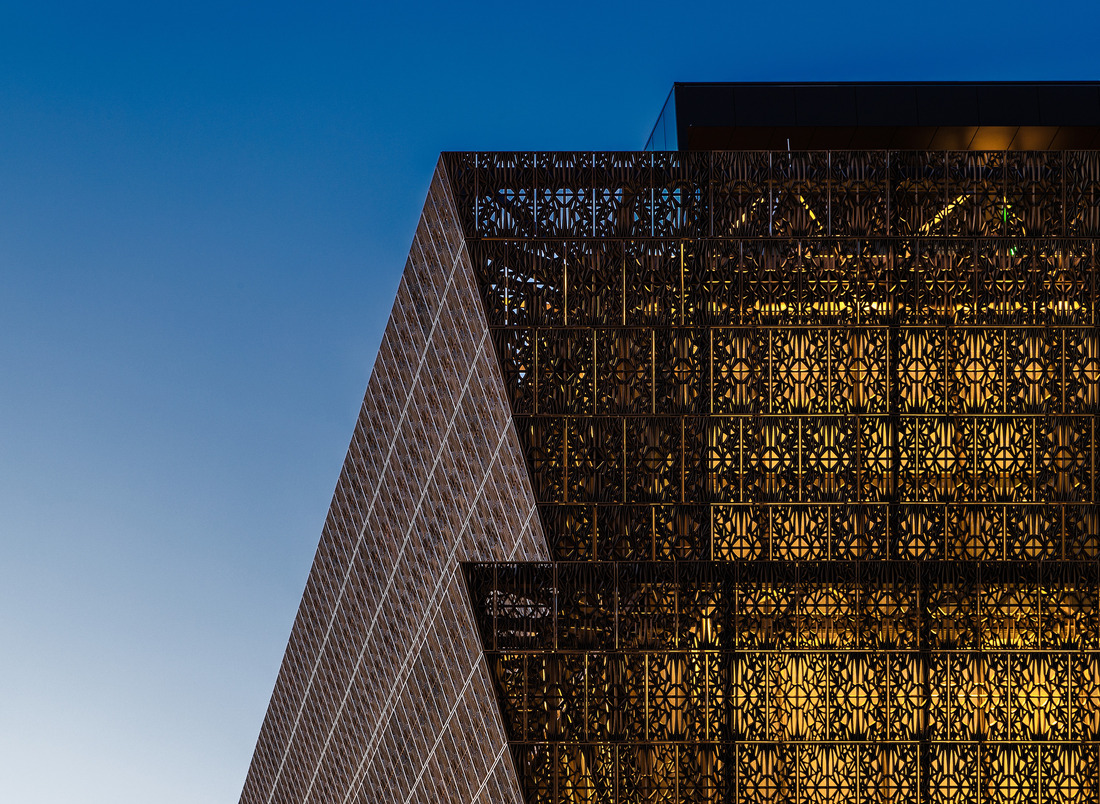

Photographer: Alan Karchmer.

Your designs often challenge conventional notions of space and form. How do you balance innovation with functionality in your architectural concepts?

Innovation and functionality shouldn’t be seen as opposites. For me, innovation is about identifying areas where improvements are necessary, and when done right, it enhances rather than conflicts with functionality. The two work hand in hand. A project succeeds when it innovates because it addresses unresolved issues in the world that need solutions. That process is thrilling—it’s exciting for the team, for the client as they discover something new, and for me, as it contributes, even in small ways, to expanding the understanding and potential of architecture today.

Can you discuss a project that required you to rethink conventional architectural frameworks and push the boundaries of innovation?

A project that Adjaye Associates is completing right now, which is important to me, is the Studio Museum in Harlem. You’re going to hear a lot about it this fall. What I love about it is that we studied what a contemporary art museum can be. In doing so, I realized that much of the process and conditions that make art happen are often lost to the public as the artwork moves from the invisible to the physical. The Studio Museum is a great example of making the artist’s studio more visible within the institution.

At the Studio Museum, we’re not just constructing the final place of presentation; we’re also building studios where children, students, clients, collectors, and patrons can see where the artists are working. These studios are incubated spaces that form relationships with the teaching environments, and these, in turn, connect to the exhibition spaces. Collaborating with Thelma Golden and her team has been incredible, and we’ve developed a way to see the museum as both an experiment and a laboratory.

It’s more like a laboratory where visitors can see the finished work and also trace it back to its origins. In organizing the exhibition spaces, we’ve also rethought the public spaces—there’s no box-like auditorium. Instead, the public areas flow into each other seamlessly. These spaces—where you arrive, meet, wait, listen, hear, experience events, and view art—are all interconnected.

For me, this project is about socializing the museum, turning it into a social condenser where visitors, students, and curious individuals feel comfortable engaging with the space and understanding the experience, not just through text or learning, but through immersion.

The Studio Museum is such an important project for me. It follows my work at the Smithsonian, but it’s the one that represents where I’ve arrived in my journey of socializing and democratizing the museum model. In my work, there’s always a pattern of shifting established models. I choose my projects carefully, only taking on those where I feel I can fully apply my skills. Sometimes we turn down projects because they don’t require what we uniquely offer.

When we take on a project, it’s about fully investing time and innovation. The Studio Museum, opening next fall, is the next big one for Adjaye Associates, and I can’t wait for the world to experience it.

Internationally, your projects span a wide spectrum, from museums to residences. How do you tailor your design approach to accommodate such diverse typologies?

The typologies have been learned carefully and gradually over time. In the early stages of my career, my work was predominantly residential, as that’s typically where young architects begin. However, I was fortunate to quickly transition into educational projects, with libraries becoming some of my first public buildings. From there, I moved into the realm of art and artists’ spaces. Most recently, we’ve ventured into religious architecture, completing the Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi, which includes a mosque, a church, and a synagogue. This was my first experience designing religious buildings.

Each architectural project introduces you to a new world, and if you’re attentive, it teaches you a great deal. My practice has now spanned almost 30 years, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to work across so many typologies. We’re comfortable working with various forms because our experience has been broad and diverse, not confined to one type. This versatility has been developed over decades, allowing us to approach different typologies with confidence and ease. For example, our latest endeavor is our first skyscraper, 130 William, which has introduced us to yet another typology, and we’re excited to explore its possibilities.

Architecture is an inherently political art. How do you navigate the political aspects of your work, especially when designing public buildings?

I’m glad you said that because most people don’t think of architecture as political. For me, architecture is entirely political. I always say architecture outlasts politics. Architecture lives longer than politics. So, for me, it’s more eternal. You work within the politics of your time because politics is where the public lives.

Politics and the public are intertwined, constantly negotiating what will be important. If you’re interested in shaping public spaces, you have to engage with politics. It’s a relationship that can burn you, lift you, celebrate you, or discard you—it’s like riding a bull. You find yourself in a complex situation, but if you want to engage with the public, you don’t have a choice but to be involved. It’s always a challenge. Sometimes a place may seem ideal to work in, and then suddenly, it’s no longer the best place. Another place then becomes a great opportunity.

In those moments, we ask ourselves: Who are the clients? Who are we designing for? That’s what matters—understanding the community that will be the custodians of the project. Whether they are under an oppressive regime or a more liberal one, both systems have their complexities and challenges. While we are political, we’re not here to judge. Our focus is on supporting the communities we work with, understanding their goals, and contributing to the good of their society. For me, the politics of architecture is about gradual change, one step at a time.

It’s not about grand, sweeping transformations. It’s about demonstrating a better world through small, meaningful contributions. When people see it, they might say, “Wow, that’s great. Can we do something like that? Can we use this?” That’s the way I believe we contribute. It requires moving beyond the immediate circumstances while staying aware of them.

Is there any dream project you’re still eager to pursue? Do you feel like you’ve done everything?

I’m very interested in infrastructure, which I wasn’t before. Right now, we’re working on a railway station, and I’m enjoying it because it’s the first time I’ve had such a project. I fly all the time, but no one has ever asked me to design an airport. I’m probably an expert on airports with all the traveling I do! I’d love to take on some infrastructure projects. I think that’s the next big challenge.