Shirin Neshat is an Iranian-born artist and filmmaker living in New York. Neshat works and continues to experiment with the mediums of photography, video, and film, which she imbues with highly poetic and politically charged images and narratives that question issues of power, religion, race, gender, and the relationship between the past and present, East and West, individual and collective, through the lens of her personal experiences as an Iranian woman living in exile.

Neshat has held numerous solo exhibitions at museums internationally, including the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; The Broad, Los Angeles; Museo Correr, Venice, Italy; Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C.; and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Neshat has directed three feature-length films: “Women Without Men” (2009), which received the Silver Lion Award for Best Director at the 66th Venice International Film Festival; “Looking For Oum Kulthum” (2017); and most recently, “Land of Dreams,” which premiered at the Venice Film Festival (2021).

Neshat directed her first opera, Verdi’s “Aida,” at the Salzburg Festival in 2017 and 2022, which will be restaged at the Paris Opera House in 2025.

Neshat was awarded the Golden Lion Award, the First International Prize at the 48th Biennale di Venezia (1999), the Hiroshima Freedom Prize (2005), the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (2006), and in 2017, she received the prestigious Praemium Imperiale Award in Tokyo.

She is represented by Gladstone Gallery in New York and Goodman Gallery in London.

An Interview with Shirin Neshat

By Carol Real

Throughout your career, you’ve overcome significant personal and political hurdles, including your experiences during the Iranian Revolution and your battles with anorexia. How have these experiences shaped your artistic voice and vision?

My body has always been directly impacted by any emotional or psychological issues that I’ve faced. The first instance of anorexia came when I was sent to a boarding school in Iran. Leaving home to stay in a Catholic dormitory, and being far away from my loving family was very painful. My body reacted so severely that I eventually had to be sent back home.

Later this battle resurfaced when I came to the US, and the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution severed my connection to Iran and prevented me from seeing my family for a long time. It was quite devastating for me as a young woman living in America alone.

So it seems like my physical problems and anorexia have always been tied to my struggles with the experience of displacement and abandonment. This may explain why the core of my ideas and narratives are so often focused on women’s bodies in relation to emotional, psychological, and political trauma.

Your work articulates the struggles of marginalized women globally. How do you navigate the emotional intensity of these themes, and what personal rituals or practices do you find most therapeutic in managing this impact on your mental health?

I never intended, nor do I believe, that my work serves as a voice for marginalized women, especially in a country where I no longer live. Therefore it would be inaccurate for me to claim that my work specifically addresses the plight of oppressed women in Iran, globally, or anything of that scale.

What I do incorporate into my work however are the struggles that I face personally as a woman and as a human being. And often, my personal experiences reflect those of other women who are also marginalized or belong to minority groups, or who, like me, have been exiled or have lived under oppressive cultures.

Therefore, while my work is first and foremost deeply rooted in my own experiences as a woman, it is not intended to be a definitive statement about the situations of other women, nor do I presume to know their experiences better than they do. However, there is a sense of identification with the plight and circumstances of other women, particularly those from my region.

In your exploration of themes like shame, guilt, and sin within the context of the female body in Islamic culture, what have been the most challenging aspects of translating these complex emotions into visual art?

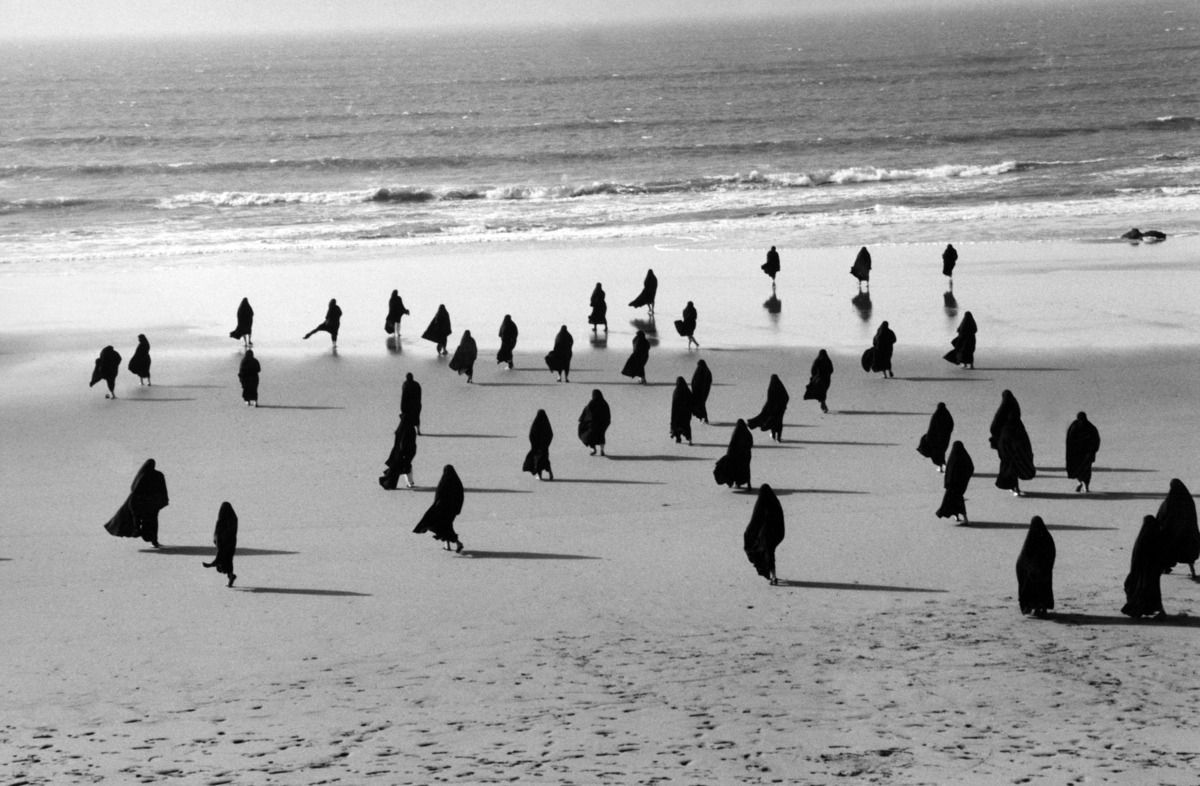

The most challenging aspect has been the internalization of shame imposed by societal regulations, which are often driven by male perspectives. For many years, my focus was on the concept of veiling in Islamic cultures like Iran, where women are told they must cover their bodies to prevent any sexual provocation and temptation in the public arena. This seemed problematic to me—why do women have to conceal their bodies because men can’t control their sexuality?

Growing up in Iran, I remember how many women of my generation lived with a lot of anxiety about their bodies—as if there was something inherently wrong and shameful about their bodies, all of this of course reinforced by religious rhetoric.

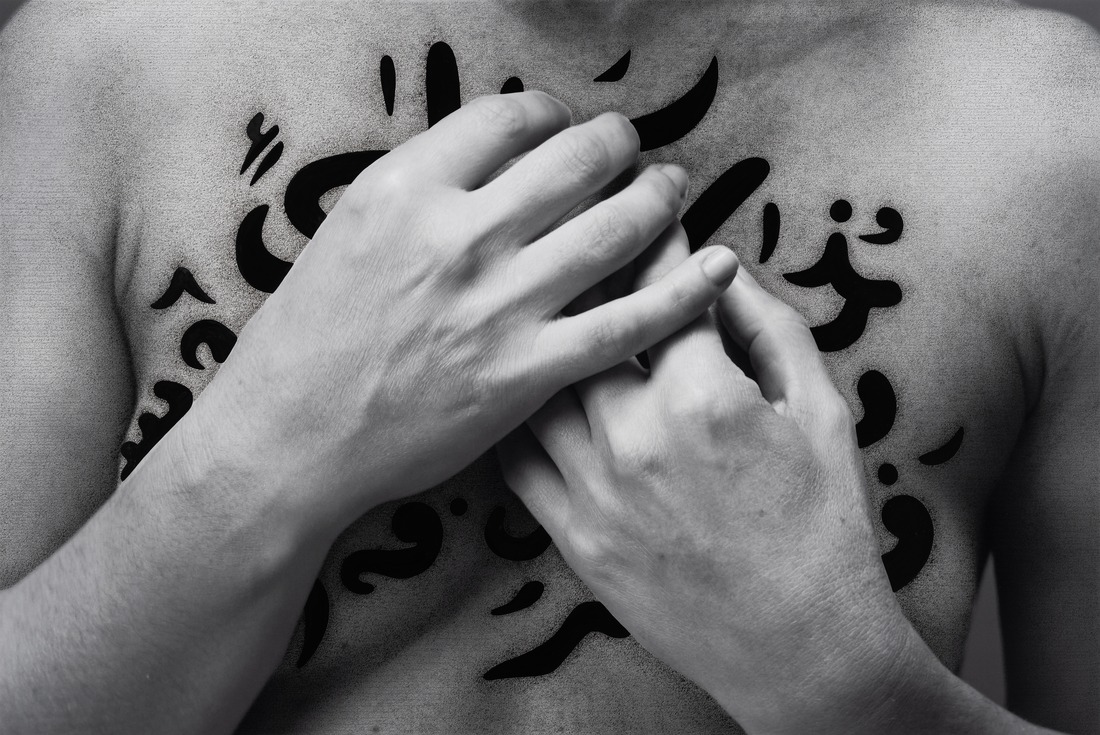

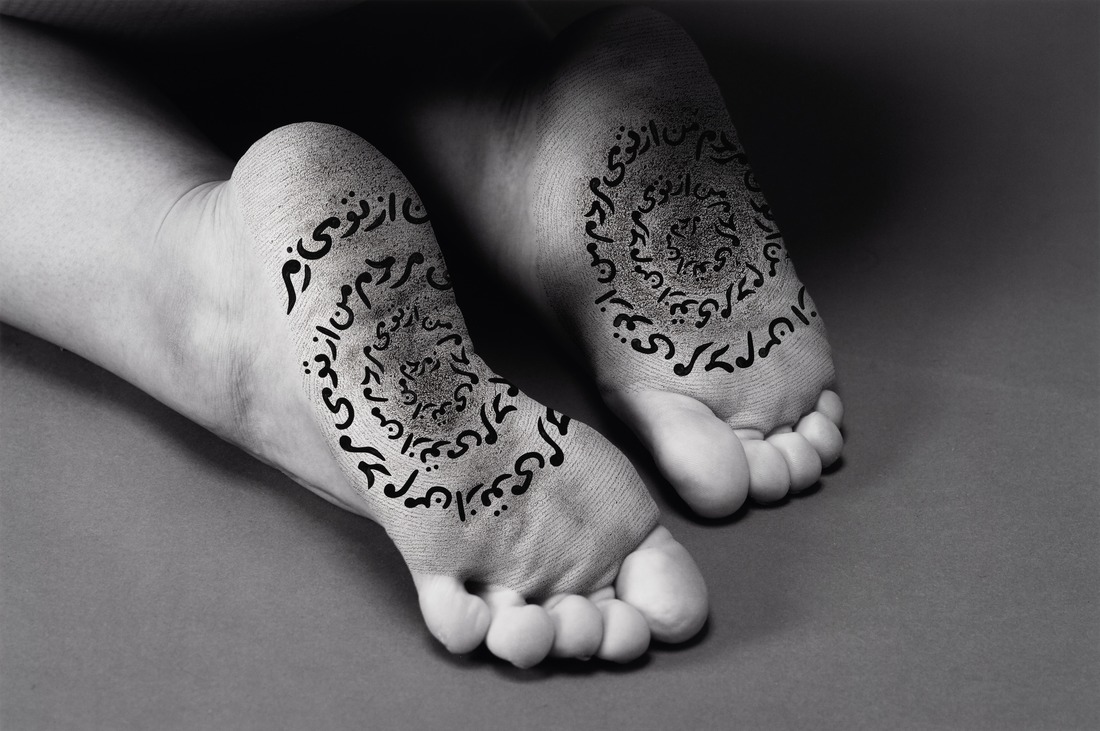

Many of my photographic series have revolved around the female body and the psychological state of women living in oppressive cultures. The “Unveiling” series framed the body as a place of desire, sexuality yet shame and sin; while the “Women of Allah,” series raised the issue of the woman’s body as a battleground for men’s political and religious rhetoric and ideologies. I often incorporated poetry by Iranian women poets, whose text directly expressed such views as Forough Farrokhzad who relentlessly tackled the female experience in Iran within religious and traditional taboos.

In the latest work, the video “The Fury,” I explore the subject of the female body as an object of desire and violence, and more specifically the sexual exploitation of women in the prison system. Despite being a victim, many women prisoners go on to feel ashamed of their bodies, and many never recover psychologically from such trauma.

Your art has been described as both politically charged and deeply poetic. How do you balance these elements in your artwork?

It’s a pertinent question about my work, as the interplay between politics and poetry fundamentally characterizes Iranian culture. Iranians are a people of ancient mystics and poets, possessing a rich heritage of poetry. Yet, concurrently, we have endured one of the darkest chapters of modern history. Internationally, we are recognized through the prism of fanaticism that is associated with the Islamic Republic of Iran. Consequently, our identity is torn between a lyrical culture with a profoundly rich history, and four decades of an oppressive dictatorship and Mullahs.

My work navigates this dichotomy, exploring the political reality alongside the cultural, intellectual, and emotional life in Iran, not just in ancient but in modern and contemporary times. Iran continues to produce remarkable poets, writers, filmmakers, and artists yet its identity in the world often conflicts with who we truly are. So I would say this identity conflict, especially that of “Persians” versus “Muslims” is at the very core of who I am as an Iranian, and inherent in my concepts and narratives.

You’ve depicted the severe mental traumas experienced by women subjected to extreme violence. In preparing for these roles, how do you ensure that your portrayal is sensitive and respectful to these women’s experiences?

Although I live outside Iran, I feel deeply connected to the Iranian community and I am acutely aware of the price Iranian women pay for their freedom and artistic expression—or the lack thereof. Much of my inspiration comes from Iranian women, especially authors and poets who have not only explicitly written about the female experience in Iran but have themselves lived very difficult lives.

One of my most important experiences came when I adapted a book into a film called “Women Without Men,” written by the respected Iranian author, Shahrnush Parsipur, whose book has been banned and was imprisoned. I value the time I spent with Shahrnush in developing the film, which was eventually completed in 2009, learning about her challenges as a prisoner and as someone who has been battling with mental illness, yet she remains a historical figure in our literary culture.

What tools do you think can help a woman overcome such a hurdle?

I am not sure how to answer this question. I believe that most women, to varying degrees, have experienced sexual assault at some point in their lives. However, some depending on the extent of their experience, can prevail and overcome, and some don’t. In the case where women are repeatedly sexually exploited in prison, I don’t see how a complete recovery is possible.

Art as a form of rebellion is a significant theme in your work. Can you discuss a specific artwork where you felt your artistic expression was especially crucial in challenging societal norms or sparking dialogue?

I view art as a tool for communication, creating dialogue, to make people think and feel in ways they normally wouldn’t. In my opinion, the most effective art is the kind that allows the public to derive their own interpretations.

In my case, the act of making art itself almost takes an activist’s position, as each concept or narrative tends to frame a critical and at times controversial socio-political or religious issue. I see art and being an artist as a gift, as it allows me to have a voice, to express my views, and to create dialogue. Each work takes a different direction and explores a new theme.

To discuss one specific work, I would mention my video Turbulent, which focused on the absence of Iranian women in Iran’s music industry and how they are deprived of any rights to perform publicly. Yet, ironically we face a female singer who explodes with her powerful voice, breaking all traditional, classical rules of music and delivering the most passionate, innovative, and radical performance.

There’s a pronounced sense of melancholy that permeates your art. Can you share how this emotional tone serves the narratives you choose to depict, and why you believe it resonates so strongly with your audiences?

For a long time, I didn’t fully understand the source of this melancholy in my work, but now I do. It must mainly stem from the rich culture and tradition of mysticism within Iranian culture. For us Iranians, melancholy is not depression but a form of reflection, a way to simultaneously acknowledge the world’s pain and beauty, which hold equal weight. We are accustomed to listening to melancholic music that, while it may bring us to tears, it also invigorates us.

In essence, melancholy is rooted in our poetic tradition—deeply heartfelt and transcendent in everyday life. I view melancholy as a means to reflect and comprehend both personal and universal pain, yet also appreciate beauty. And finally, I feel like infusing poetic qualities into my work helps to neutralize some of the politically charged nature of my subjects, and allows the audience to emotionally engage in the work.

Considering the unpredictability in both your life and work, how do you approach the creative process? Does this unpredictability fuel your creativity, or do you find it more challenging to work within such a dynamic?

Living as a nomad, the notion of impermanence seems to be central to my life and artistic practice. I seem to intuitively thrive on the idea of unpredictability, always embracing new environments, new chapters, new encounters, and new challenges. And that may explain why I keep moving from one medium to another. I like new beginnings and not knowing exactly where I’m heading. Of course, the risk could be a failure, but I rather take that risk than stay in the same spot and repeat myself.

As much as I like to feel safe and secure, there’s something wonderful about embracing the unknown and reinventing yourself. I see how each time I’m taken out of my comfort zone I discover new tendencies that I never knew I had.

Collaboration has played a significant role in your career. How do you develop collaboration, and what value do you think it adds to your artistic process?

Collaboration is not easy, it requires a lot of patience and respect but can be quite wonderful and stimulating. You cannot effectively collaborate if you constantly try to enforce your own opinions. I do my best to stay open, and patient, and give space to others to present their ideas before making any decisions.

In recent years, I have especially welcomed collaborating with people from other fields than my own. These days, I’m working a lot in cinema, so I often find myself working with scriptwriters, producers, actors, and most recently I’m quite occupied with opera, so I’m in close collaboration with a dramaturgist, singers, conductors, stage designers, and choreographers. Each one of these people demands a very different kind of artistic attention from me, which I find both nerve-wracking but incredibly invigorating and creative.

Looking ahead, what new themes or challenges are you excited to explore in your art? Do you have any specific projects or collaborations that could help highlight the issues you care about?

In the last few years, my work has been set in the US, but always with an Iranian woman as the protagonist. Inspired by my own experiences and my lens into America, these new works mostly touch on the kind of cultural and political dualities that I see as an immigrant. The new work tentatively called “Do U Dare!” is a short video that is intended to turn into a trilogy. The first episode will be a low-budget video to be shot in a few weeks, in Bushwick, Brooklyn where I live, with a predominantly Hispanic immigrant community.

In a very stylized and somewhat surrealistic approach, the theme of this new work will address the nature of men in positions of power, whether political, religious, or corporate, whose deceptive rhetoric is often targeted toward the most vulnerable and economically deprived citizens.

Is there any question that you wish you had been asked in an interview that no one has asked you before?

Probably the question that nobody has asked me before is whether I would have been an artist if I hadn’t lived the life that I have. Of course, all artists’ work is personal and reflects their experiences in this world to some degree. However, in my case, it’s more extreme as I chose to abandon being an artist. And how my return to art was not a career move but integral to my personal life circumstances. Art became an urge, a tool to reconnect with my past that I had lost contact with, including my family and country which I desperately wanted to engage with, even if from a distance.

Where do you think you would be if you were not an artist? Perhaps in another profession?

I am not sure, but I do tend to feel comfortable with being of service to others. I worked at a non-profit organization for ten years. I could see myself as a human rights activist, supporting good causes.

All images courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista