Within the walls of a home that exudes artistry from every corner, I had the privilege of sitting down with Robert Storr in his Brooklyn abode, a luminary in the world of art and criticism.

Art adorned the space, and books sprawled in every direction, their well-worn pages filling the air with the comforting scent of knowledge. It was a haven for creativity, a sanctuary of ideas.

As both a painter and curator, Robert’s influence on the art world has been immeasurable. His latest curated show, “Retinal Hysteria,” has become a must-see in New York City’s art scene, promising to captivate and provoke, offering a glimpse into the disorienting intensity that defines our contemporary world.

Robert Storr’s contributions to the art world extend far beyond the walls of galleries and museums. His journey has taken him from Swarthmore College to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and, later, to the prestigious Museum of Modern Art, where he curated groundbreaking exhibitions and made a mark that still resonates today. His role as a professor and dean at various institutions has nurtured the next generation of artistic minds, shaping the future of art and criticism.

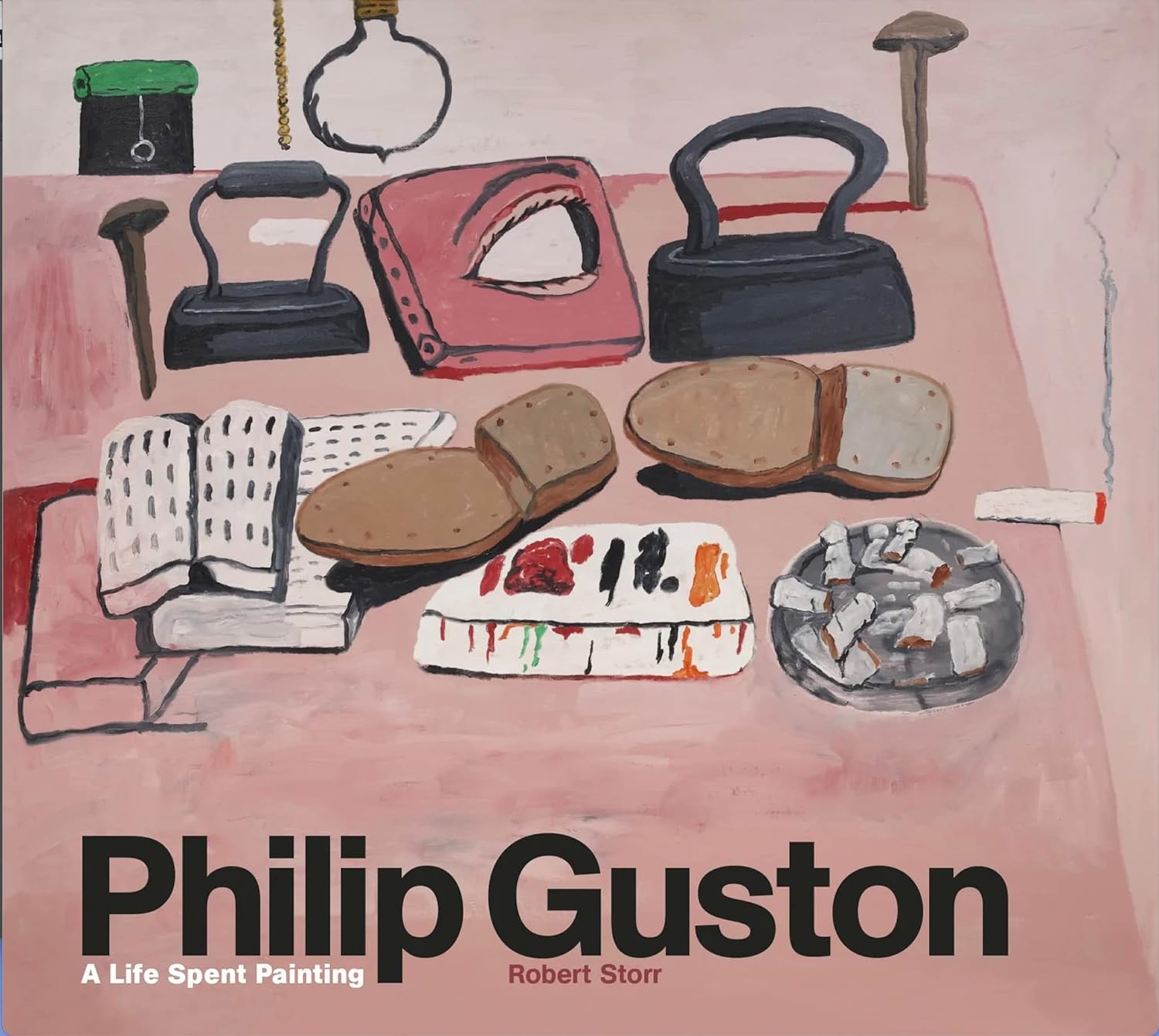

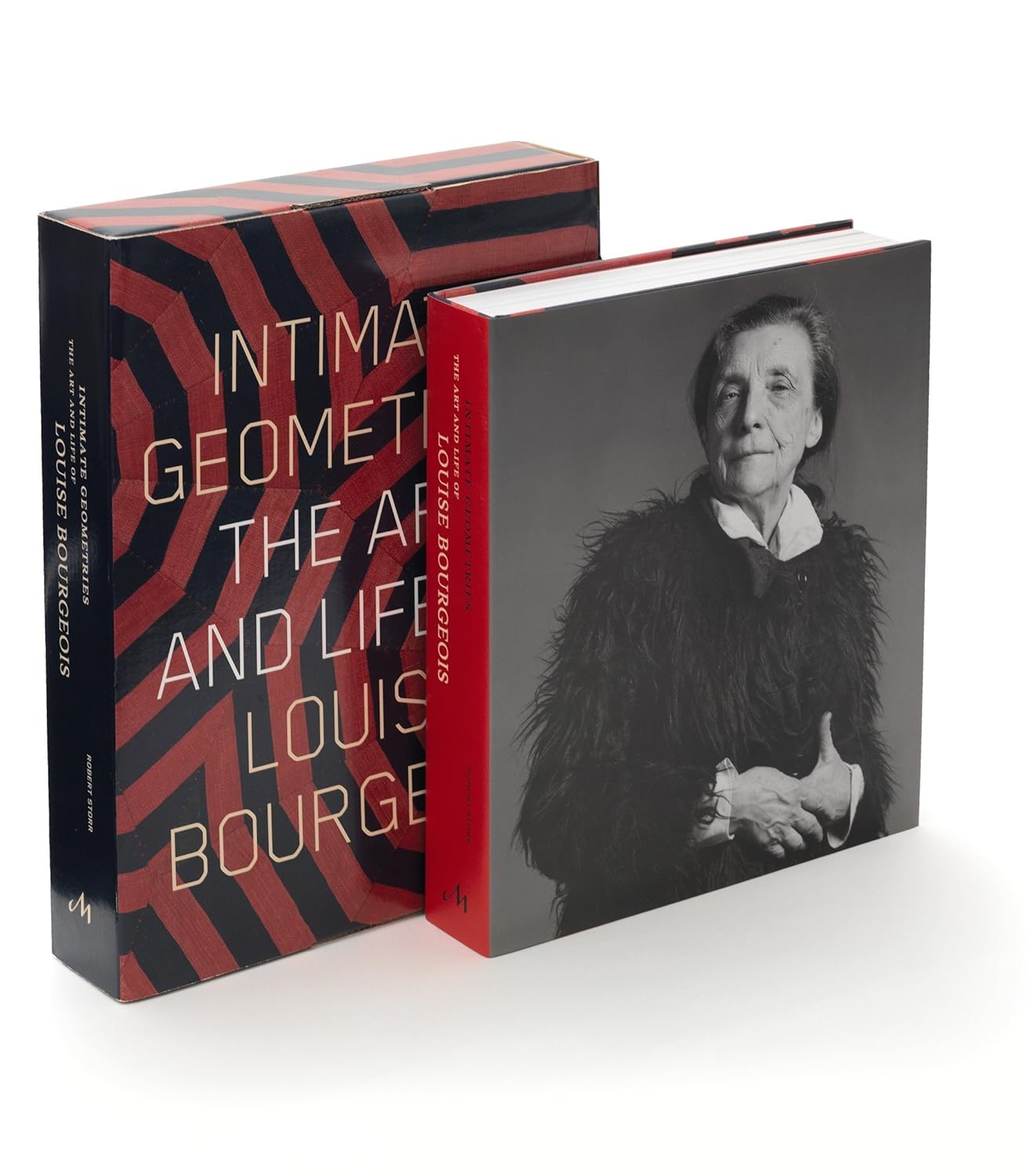

As a writer, Robert Storr’s words have graced the pages of renowned publications like Artforum, Art in America, and Frieze, showcasing his insightful perspective and deep understanding of art. His extensive catalog of books and essays, including “Intimate Geometries: The Art and Life of Louise Bourgeois,” attests to his dedication to the craft of art criticism.

The accolades bestowed upon Robert Storr are a testament to his indelible impact on the art world, from grants and awards to honorary doctorates and curatorial distinctions. He served as the visual arts director of the Venice Biennale, the first American to hold such a prestigious position, solidifying his global influence on the arts.

Today, as he continues to push boundaries and challenge conventions in the art world, Robert Storr remains a true legend in the cultural landscape of New York City and beyond.

By Carolina Real

Let’s start with your early life and education. Can you share some insights into your early life and educational experiences at Swarthmore College and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago?

Swarthmore had a very limited, in fact, no studio art program, but it had a decent art history program. So I took two art history courses there. That’s all the art history I ever took. However, I had two exceptional teachers in this area, and I learned a lot. It was a formative experience for me. One of them had been a painter on the WPA program. And I was very struck by his ability to separate his personal preferences from teaching us about artists he felt we should know. “I hate Courbet’s work,” he announced, “but I’m not going to teach you why I hate it. I’m going to teach you what I know about him.” That left a strong impression on me. It made me realize that you don’t have to like something to engage with it seriously. The other professor taught the history of printmaking. He introduced me to artists like Schongauer, Durer, and Rembrandt. I learned a lot from him as well.

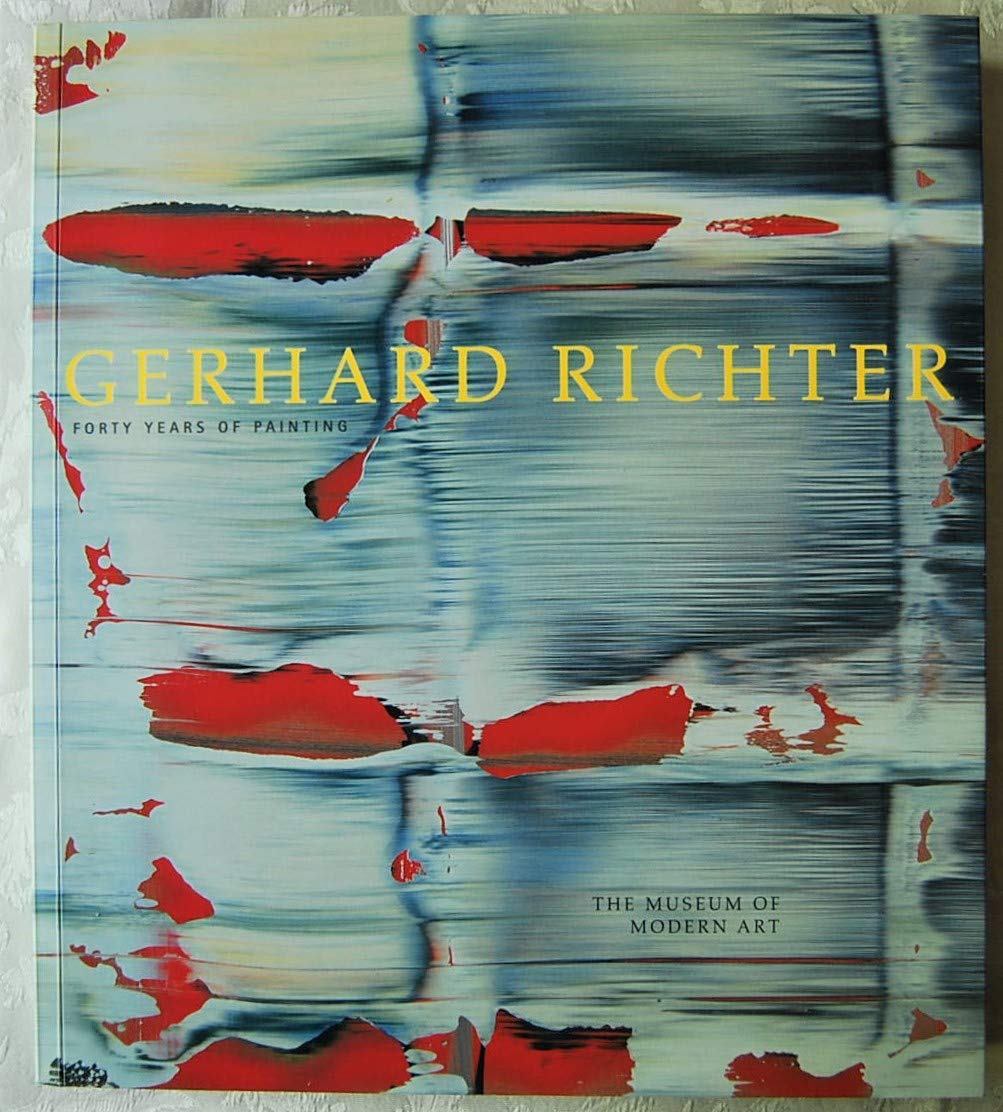

As a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, you organized exhibitions that brought artists like Elizabeth Murray, Gerhard Richter, and Tony Smith into the public eye. Can you tell us about your approach to curating and the impact these exhibitions had on the art world?

Certainly. All three of the artists you mentioned were not as well known at the time as they are today. Richter, in particular, was just starting to gain wider recognition when I decided to feature him in an exhibition, which took nearly six years to schedule. However, when it finally happened, it had a significant impact. Simultaneously, I acquired Richter’s Baader-Meinhof inspired October cycle for the museum. It was a major acquisition and it was a lengthy process, as I had to secure the necessary funding and reassure Richter that this acquisition was not an attempt to take his work away from Germany but to place it in the history of painting.

Tony Smith was also an artist who deserved more attention, and I organized an exhibition that extended beyond the museum’s galleries, including outdoor installations on the streets of New York. Elizabeth Murray, although not widely recognized by the art world, was a bold and dynamic painter who didn’t conform to conventional tastes. I promised her an exhibition at the Venice Biennale, and I delivered on that promise. Although she was very ill, she had a wonderful experience, and her work gained international exposure.

You also had a show at Francine Seder’s gallery. Can you tell us about your work and what you aim to convey with it?

The exhibition at Francine’s gallery was unexpected. My friend, Denzel Hurley, a painter, had an exhibition with extra space, and he asked if I’d like to fill it with my work. I accepted the invitation, and it turned out to be a positive experience. Denzel became a close friend, and the show featured abstract paintings of mine that rhymed with his. These paintings explore subtle shifts in placement and execution, focusing on fine distinctions that challenge viewers to examine the artwork closely without trying to look past what is directly in front of them in search of “deeper” symbolic meaning. The act of seeing is crucial in my work, and I assume that viewers approach it with curiosity and a willingness to engage.

Do you see any relationship between your curatorial work and your artistic endeavors? How do you balance these two aspects of your career?

The main challenge is finding a balance between curatorial work and creating art. They compete for my time and focus. I’ve never felt the need to develop a grand theory about my art or insist that it’s of utmost importance to humanity. I approach it with humility and a desire to see where it leads. My art is important to me, but I don’t elevate it above other aspects of life. I take it as seriously as it deserves to be taken, adapting my approach based on the project at hand. While I don’t follow a consistent formula, I rely on fairly constant variables, using them differently each time to continually learn and evolve as an intuitive painter.

You’ve been described as a “vital link between the museum world and academia.” How do you balance these two worlds in your career?

The idea that I’m a link between the academic world and the museum world is more of a perception held by others than a self-perception. I have never really considered myself a part of the academic world, although I am familiar with it and have taught in various academic settings. My true affinity lies with the world of practicing artists, and I see myself as a bridge between that world and the museum realm. During the recent opening of the exhibition, you could observe many artists who participated, and they might not have had the opportunity to showcase their work in such a context or alongside each other without this bridge. Serving as this link is a mixed blessing, but it’s worthwhile if it benefits the people I connect. I believe I’ve been able to facilitate this connection effectively. Regarding the current academic world, it often uses an opaque vocabulary that can be incomprehensible even to its users. My approach has been to write clearly and directly, much like a traditional critic or historian, while engaging with contemporary art. I’ve aimed to counteract the trendiness and the proliferation of various “-isms” as well as postmodernist jargon by speaking straightforwardly to the ordinary viewer, respecting their intelligence while providing them with the information and artworks they need and probably do not have in order to think for themselves.

Your role at the Venice Biennale, serving as the first American Director of Visual Arts in 2007, must have been a unique experience. How did this role influence your perspective on international contemporary art?

The Venice Biennale is a unique entity, unlike anything else in the art world. While there are many exhibitions referred to as “biennales,” none compare to the Venice Biennale. The closest counterpart, Documenta, is not another biennale but rather an omnibus exhibition taking place every five years that encompasses a wide range of art from around the world. During my time at the Biennale, I grappled with the challenge of limited funding, which made it difficult to realize the event properly. However, I had a clear vision—I aimed to make the Biennale as genuinely international as possible, going beyond just the major cities and countries to include art from places that were often overlooked. I was the first American curator to visit an African biennale and bring art from Africa directly to Venice. This was an important step in addressing issues of racial division, something that resonated with my experiences growing up in Chicago. My goal was to break down barriers and work towards a more inclusive art world. The Biennale was an extraordinary experience for my entire family, as we lived in Venice for six months, immersing ourselves in Italian culture and daily life. I was committed to making each exhibition in the city unique and tailored to its spaces while actively participating in its cultural and social life.

Your book, “Intimate Geometries: The Art and Life of Louise Bourgeois,” received the FILAF D’OR. What inspired you to write about Louise Bourgeois, and what message did you aim to convey through this work?

Louise Bourgeois was a significant figure in both the art world and my life. I had known her for years before joining the Museum of Modern Art, and I had the privilege of visiting her home, exploring her archives, and witnessing her studio firsthand. Our close relationship allowed me to speak authoritatively about her work once I was at the Museum of Modern Art. However, my connection with Louise went beyond professional collaboration—I had been deeply moved by her work since my student days at the Art Institute of Chicago. Over the years, her art continually resonated with me and left a lasting impact on my mind. Meeting her in person and engaging in direct conversations with her was an invaluable experience. My book on Louise Bourgeois was a project that I worked on for 30 years, representing a significant commitment. It was a labor of love.

Regarding the most important lesson I learned from her, it’s challenging to pinpoint a single aspect. However, if I were to distill it down, it would be not to have specific expectations of others but to approach life with an open mind and to assert your will on circumstances as much as possible. It’s about making your intentions clear and doing your work, irrespective of others’ opinions. This mindset is crucial in any situation, not just in relation to Louise Bourgeois but in life in general.

Can you share some insights into your creative process as both a writer and a visual artist?

As a visual artist, I seek to explore visual ideas and propositions intuitively rather than through systematic or logical methods. I am not a minimalist or a strict systems artist. Instead, I draw inspiration from artists like Robert Ryman, Sol LeWitt, and Mondrian, not by imitating their styles, but by embodying the spirit in which they worked. My goal is to find my own unique way to express that spirit.

When it comes to writing, I am not “a natural.” My early struggles with dyslexia made me approach writing differently. I learned to articulate my thoughts by transcribing my inner dialogues onto paper. I avoid writing in a manner that is overly complex or obscure. Instead, I aim to communicate clearly and directly, making my content accessible to a wide audience. My belief is that writing should serve the purpose of conveying information and ideas effectively to others, rather than alienating or confusing them. This approach stems from a sense of responsibility to share knowledge and insights with those who may have less access to information.

In summary, my creative process in both art and writing revolves around intuitive exploration and clear communication, allowing me to express my ideas and engage with others effectively.

What is the significance of giving back to the art community, and how has your involvement in committees and foundations benefited both you and the community itself in terms of fostering the growth of challenging art and artists?

OK. it’s my view that there is an “art world” and then there is an “art community.” And the art world is mostly what we know it to be – museums, galleries, etc. The art community is composed of people who devote themselves to this activity, in whatever way they choose. They could be artists, writers, curators, collectors. I believe I owe a lot to the art community. From which I’ve benefited greatly, and I think I should give back if I can by offering something useful to other people, to help ease the way for challenging art and artists to flourish. So, I’ve volunteered to be a member of numerous committees and foundations, advising people, often without pay, to contribute to these institutions and individuals. I also learn a lot in the process because I meet people I otherwise wouldn’t, exchanging ideas with those who have entirely different perspectives. Giving back is very important in this context.

How do you think the digital age has influenced the art world, from creation to curation to criticism?

Well, you’re speaking to someone who identifies as “Paleo-digital.” I’m not comfortable or familiar with this world, and it’s beyond my grasp. I’ve been advised that I could figure it out, but I honestly don’t think I can. Nor do I wish to invest the time it would require. I accept my limitations when it comes to new media and communication systems. I can barely handle emails and text messages, and that’s about it. As for those who can navigate this digital landscape with ease, more power to them, but it’s not my forte. I find traditional forms of reading and writing on paper more suitable for my work. However, I acknowledge that we’re experiencing a profound shift in human consciousness driven by technological changes. I’m not against it, but I don’t personally find it appealing or practical.

I do have a young artist friend Asher Liftin who uses artificial intelligence as a tool in his work. He creates unique pieces by inputting specific instructions into his computer, generating numerous combinations, and then selecting the ones that resonate with him. While I admire his approach, it’s not something I can do myself. So, I am interested in these developments, but they are not for me.

Regarding digital art, I think it’s essential to differentiate between using digital means for idea development and using digital technology for execution. Personally, I find more resonance in hand-made images derived from digital forms. It adds a dimension to the work that machine-made art lacks. This act of translating machine-made imagery into something handmade brings it closer to my comfort zone, though it’s not a requirement for all artists.

How has the global art landscape changed over the years, and what role do you see American artists and institutions playing in it?

I’m uncomfortable with the term “global” because it tends to homogenize diverse cultures and experiences. Even commercial products like Coca-Cola have different recipes to cater to various tastes worldwide. The art world can’t truly be “global” because every culture has its unique perspectives and expressions. I find the differences between cultures more interesting than the similarities. Ideas evolve differently in different environments, and that’s what fascinates me. I believe Portuguese philosopher Miquel Torga put it well when he said, “The universal is the local without walls.” Everything we experience happens within our personal world’s smallness. When it transcends those boundaries, it becomes universal. You can’t set out to create a universally much less globally appealing work of art; it’s not possible. “Globalization” is best left to the economic or military spheres. It may be a trendy term in art, but it oversimplifies the complexity of human culture.

As both an artist and a curator, you have a unique perspective on the art world. How do you personally define success for an artist, and what are the key factors that contribute to an artist’s success in your view? Can you share your insights into what makes an artist’s work stand out and gain recognition in the competitive art scene?

Success for an artist is defined by his or her ability to pursue a specific artistic vision and control the creative process to the extent possible. There is no one-size-fits-all definition of success. Some artists may aim for Hollywood-style fame, while others have different aspirations. Picasso and Gerhard Richter, for example, achieved remarkable success in their careers, but they represent different paths and ambitions. It’s important to acknowledge that artists’ success is specific to their individual talents, circumstances, and the resources available to them. Success shouldn’t solely be defined by competition; instead, it should be about creating meaningful art that aligns with an artist’s true intentions.

Success can take many forms. For instance, Gerhard Richter may be considered one of the most successful artists by some measures such as high prices and widespread recognition. Still, not all artists aspire to or can achieve this level of fame and commercial success much less thrive under the burdens entailed. Picasso faced similar challenges with the sheer volume of his work. Success should align with an artist’s goals and the unique path they choose. Was Morandi “successful” by such standards, or Etel Adnan?

Can you predict a successful career for an artist? How can you assess the trajectory of someone’s exceptional career over time?

By the standards of my generation, I am considered a successful curator. However, I couldn’t have predicted it, and I certainly didn’t plan on becoming a curator. It’s challenging to predict success for an artist or anyone in the arts. I believe you can only evaluate an artist’s success by how they use and develop their talents while maintaining control over their creative process. Success varies greatly based on individual ambition, circumstances, and available resources. I didn’t receive formal training, excel academically, possess a clear career goal, or have an assertive personality. Still, I refused to accept second best, and that determination led me to where I am today.

I don’t believe it’s possible to predict an artist’s career. Often, we don’t know an artist’s weaknesses, and under pressure, those weaknesses can become more apparent, potentially leading to the premature end of their creativity. Success is highly individual and depends on factors like ambition, personal circumstances, and available resources. While some artists may seem destined for success, it’s not a guarantee, and unexpected challenges can arise. Success is never defined by rigid criteria, and neither should it be solely defined by competition but rather by an artist’s singular journey and contribution.

Over the years, you’ve received numerous awards and honors in the art world. Could you share your thoughts on how recognition and accolades affect an artist’s career trajectory, and do you believe they are indicative of future success?

I have received many awards that others would desire. However, I don’t dwell on them because I never expected them in the first place, and their surprise factor hasn’t worn off. I do occasionally ponder the ones I didn’t receive, and I have friends who’ve garnered much praise and prestigious prizes. It makes me wonder at times, not in terms of envy but curiosity, about what might be lacking in my work. Yet, in the long run, all of these accolades don’t hold much significance. What truly matters are the artworks I create, the books I publish, and the exhibitions I curate. These endure and define my legacy. My mother once said she’d be content if she created just one beautiful textile. Similarly, I aim to produce a few exceptional paintings that, while they may not find a place in art history, will be a testament to my individual vision. I hope they endure and bring value to those who appreciate them.

You just mentioned your mom, who was not an artist. How did she influence you as an artist?

My mother was a modest and reserved person, and her influence on me was substantial. Her quiet demeanor likely contributed to my own reserved nature and lack of self-promotion. While I believe she may have suffered from not being more assertive, it was characteristic of her generation of women. Nonetheless, I’m grateful for the lessons I learned from her and those around me who valued modesty. Being modest helps one avoid some obvious pitfalls and, in the grand scheme of things, keeps life relatively simple. We are but a small fraction in the vast universe, and our existence is fleeting. What remains are the works we create, and that’s what truly matters to me.

As someone who has written for various art publications and received awards for your contributions to art criticism, what are some common errors artists make when presenting their work in writing, and how can they effectively communicate their artistic intentions and concepts?

One common mistake is trying to create a showstopping presentation, especially in venues like biennials. Despite appearances, these events are not well-suited for dramatic productions. What truly stands out are clear, memorable contributions. Attempting grandiose spectacles often leads to failure due to technical and economic challenges. Additionally, it’s not the best approach to engage the audience. Spectacle can disempower viewers, making them passive recipients rather than active participants in the art. I believe in avoiding spectacle.

Regarding writing about one’s own work, artists should be cautious about chasing trendy vocabularies, making exaggerated claims, or trying too hard to cater to specific audiences. The goal should not be to please the audience but to present oneself honestly and straightforwardly. While some artists may naturally adopt a more elusive approach, most artists should aim for clarity in their communication. Words can complement art by clarifying intentions rather than detracting from it.

Artists may disappear into their work for various reasons, such as shyness or the complexity of their stories. However, if artists can express simple ideas plainly and gradually delve into complexity, it can enhance understanding and connection with the audience.

In this era of canceled culture, what are your thoughts on it?

I view canceled culture as a disaster. While it’s one thing to knowingly cause offense, having a hair-trigger response to any misstep in speech or expression is unreasonable. If we value the potential for art to provoke and challenge, we must accept that it will sometimes stir controversy. Artists should take risks in discussing touchy subjects. I personally have spoken on topics that some might find offensive, but I do so without malice. Offending with humor or by exposing absurdity is not the same as doing so with harmful intent. We must preserve the freedom to explore and express diverse perspectives.

You’re also a writer. Can you share some writers who have influenced you, or any words or works that have left a lasting impact on you?

Jorge Luis Borges, Gertrude Stein, and Charles Baudelaire have had a profound influence on me. I often revisit their works. For example, Borges’ “The Secret Miracle” has left a lasting impression. It tells the story of a man arrested by the Nazis while composing a verse drama. Facing execution, he experiences a pause in time, during which he desperately tries to complete his work. When the moment ends, the firing squad executes him. This story resonates with me, as it reflects the notion that one may never finish one’s work, yet we must strive relentlessly for that “secret miracle.”

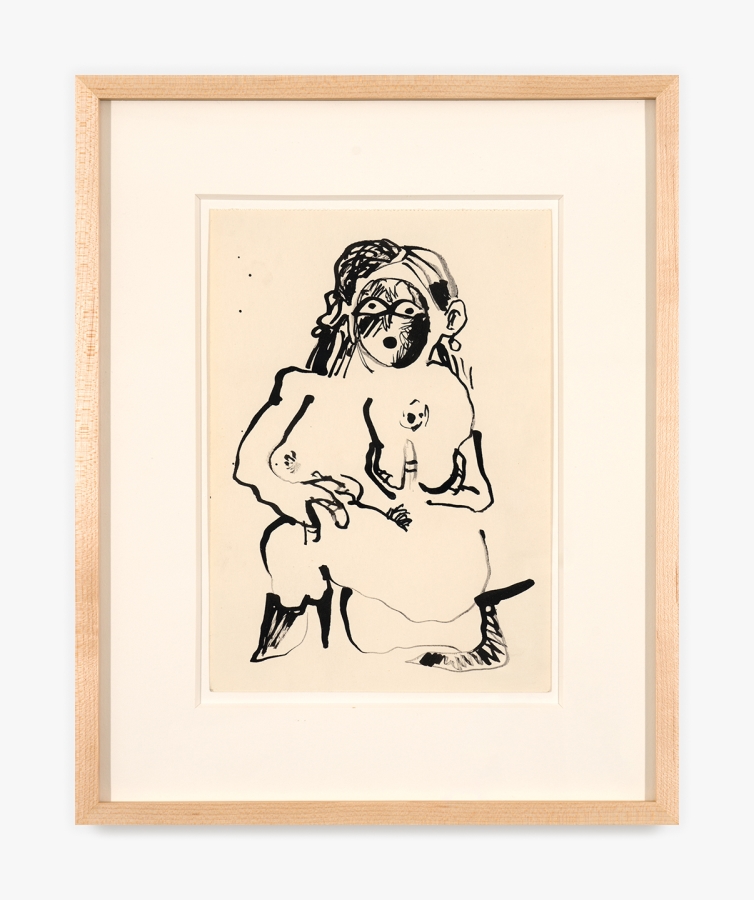

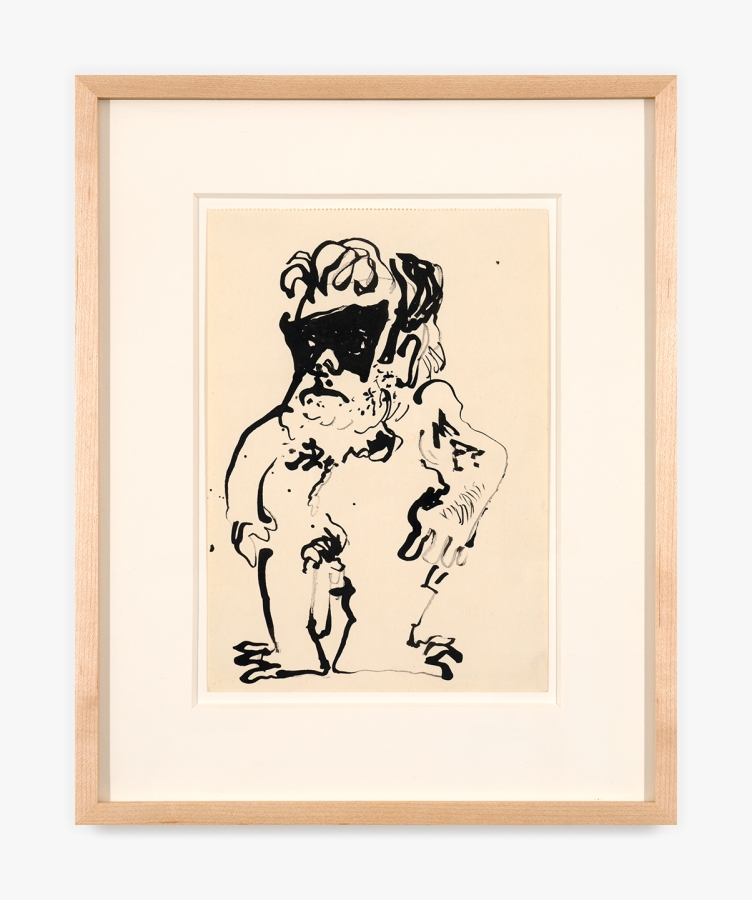

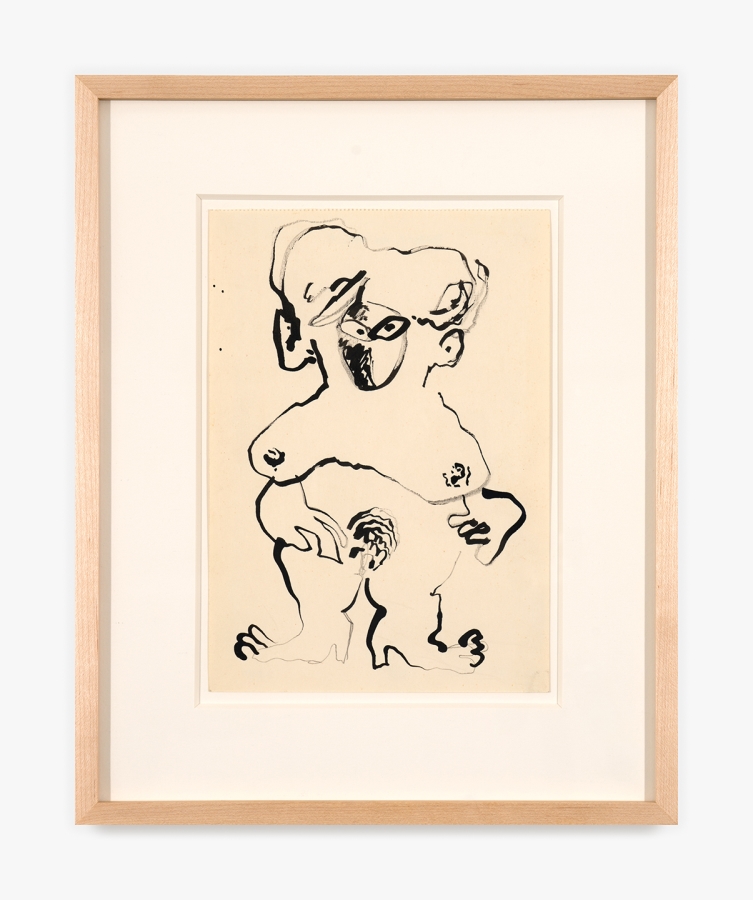

Can you tell us about “Retinal Hysteria,” the exhibition you curated at Venus Over Manhattan, inspired by “Eye Infection”?

The exhibition “Retinal Hysteria” was suggested by the gallery due to my prior work on the “Eye Infection” catalog and my familiarity with the represented artists. I agreed to curate it under the condition that I had complete creative control, free from commercial constraints. It took me a couple of years to put the exhibition together. Despite the limited space, the response from artists and viewers was remarkable. This show allowed me to present something unconventional, which wouldn’t have been possible at larger institutions like the Museum of Modern Art, given the constraints of such venues.

Are there any upcoming projects or books you’d like to share with us?

Well, I have a memoir that I’m supposed to be writing, but I haven’t made much progress on it lately. I need to get back to it. My primary focus now is on my studio work. Additionally, I have two upcoming exhibitions. One will be in New York and it features the work of a friend, Eyal Danieli, who died young. I promised him before his death that I would create a show from the pieces in his studio. Someone is coming tomorrow to assist me with that. The other exhibition is with an Israeli photographer who has captured images of Philip Johnson’s buildings from the time after he was associated with the Nazis, as well as the reactor he designed as penance in Israel. So it’s centered on a fundamental paradox or question: can a bad man make good art? Those are the only exhibitions on my schedule.

What are your guiding principles or your personal mantra?

I do have some guiding principles, with the foremost being “first do no harm.” This is somewhat akin to the Hippocratic Oath for doctors – it means not making matters worse than they already are. Another principle is not to use others to achieve your own goals; instead, you should do what is necessary to attain what you want. I have several other smaller rules I follow, but the core of it is to maintain a personal code. This code has served me well because it has made it easier for me to decline situations that might have tempted me had I not adhered to these basic principles. While my career may not have been as high-profile as some of the individuals we’ve discussed, like Harry Szeemann, I’m content with the interesting life I’ve had. I’m grateful for the opportunities and experiences I’ve encountered along the way.