Remy Jungerman, born in 1959, resides and works in Amsterdam. Initially, he pursued his education at the Academy for Higher Arts and Cultural Studies in Paramaribo, Surinam, and later continued his studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam.

Jungerman’s artistic exploration delves into the convergence of patterns and symbols within Surinamese Maroon culture, the broader African diaspora, and 20th-century Modernism. By juxtaposing fragments of Maroon textiles and materials from the African diaspora, such as kaolin clay and nails used in Nkisi Nkondi power sculptures, with elements from more conventional art traditions, Jungerman offers a peripheral perspective that enriches our understanding of art history.

In 2022, Jungerman was honored with the A.H. Heineken Prize for Art, the most prestigious visual art award in the Netherlands. His career was showcased in a retrospective exhibition titled “Remy Jungerman: Behind the Forest” at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, from November 20, 2021, to April 10, 2022. In 2019, he represented the Netherlands at the 58th Venice Biennale and was nominated for the Black Achievement Award in The Netherlands in 2017.

Acknowledged for his contributions, Jungerman received the Fritschy Culture Award from the Museum het Domein, Sittard, The Netherlands, in 2008. Additionally, he co-founded and curates the Wakaman Project, which aims to examine the position of visual artists of Surinamese origin and elevate their international profile.

Jungerman’s works have been exhibited globally, including at renowned institutions such as the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; 58th Venice Biennial; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Kunstmuseum, The Hague; and many others. His art has been featured in numerous publications and acquired by institutions and private collectors worldwide. His first book, “Remy Jungerman: Where the River Runs,” published in 2019, received accolades, including the 2019 50books | 50covers design award from the AIGA in the US. His second book, “Remy Jungerman: Behind the Forest,” accompanies his solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

An Interview with Remy Jungerman

Edited for Remy Jungerman’s studio by Sara Carder.

How do your Surinamese roots influence both your artistic process and the themes you explore in your work?”

My work has always been influenced by the aesthetics that I saw all around me in Suriname. In Suriname, no museums showcased contemporary European or American Art–there still aren’t today. I saw these works only in books, but what I saw in real life in the arts and crafts of Suriname informs my practice, especially the geometric patterns in the textiles of the Maroon people. There are seven Maroon tribes in Suriname. My mother was from the seventh tribe called the Bakabisi, the “People Behind the Forest.” The Bakabusi, along with other Maroon peoples, escaped Dutch plantations in Suriname to develop independent communities in the rainforest of Suriname. These people brought rich aesthetic traditions from Africa that changed and deepened in Suriname.

When I left Suriname in 1989 to attend the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam, I carried with me the form and pattern I had absorbed all my life in Suriname. Over the past thirty-five years, my practice as an artist has involved, in many ways, returning again and again to my roots in Suriname and exploring more deeply how the visual language of my home country echoes the form and pattern seen in textiles and other art forms throughout Africa, e.g. Kente and Kuba cloth as well as, of course, 20th-century Modernism.

Can you describe a specific moment or experience that significantly impacted your artistic journey?

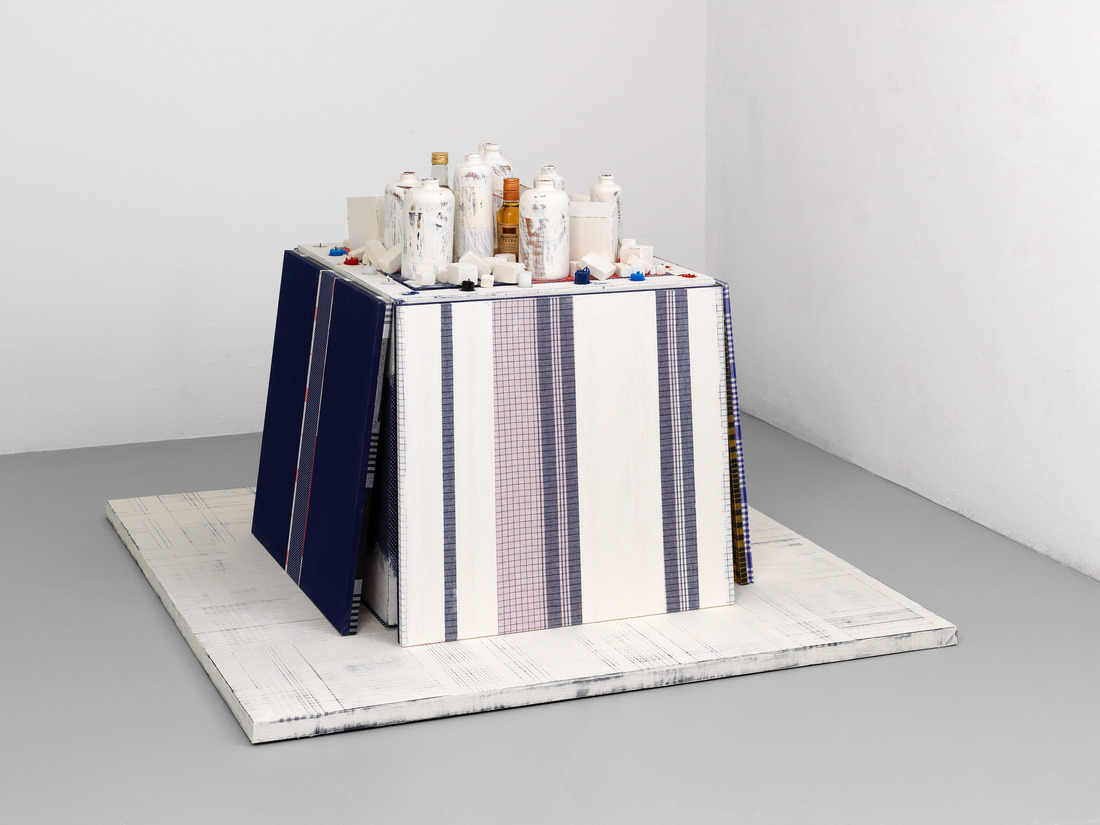

Looking back, it was a wall painting that I did at the Academy of Art and Cultural Studies in Paramaribo, Suriname, in 1988. At that moment, I was not aware of the impact it would have on my artistic journey. For this project, I was inspired by the geometric pattern from the shoulder capes of the Surinamese Maroons from the early 20th century. I began to see connections between these patterns and the 20th-century Modernism that I was learning about at art school in Suriname. It was on a return visit to Suriname in 2005, after living and working in Amsterdam for many years, that I made a conscious choice to engage with my cultural heritage. I had been making sculptures for years that didn’t have any real connection to this heritage. On this particular trip, I attended an ancestral ritual with my family that had a lasting impact. Seeing the materials used in the ritual—the textiles worn by the ritual participants, the white mineral kaolin clay they rubbed on their bodies to purify themselves, the ritual altar featuring bottles of liquid, food offerings, and other objects—I felt I had found a new language that I wanted to incorporate into my work.

You frequently integrate a variety of materials into your work. How do you decide on the materials you use, and what significance do they have in communicating your message?

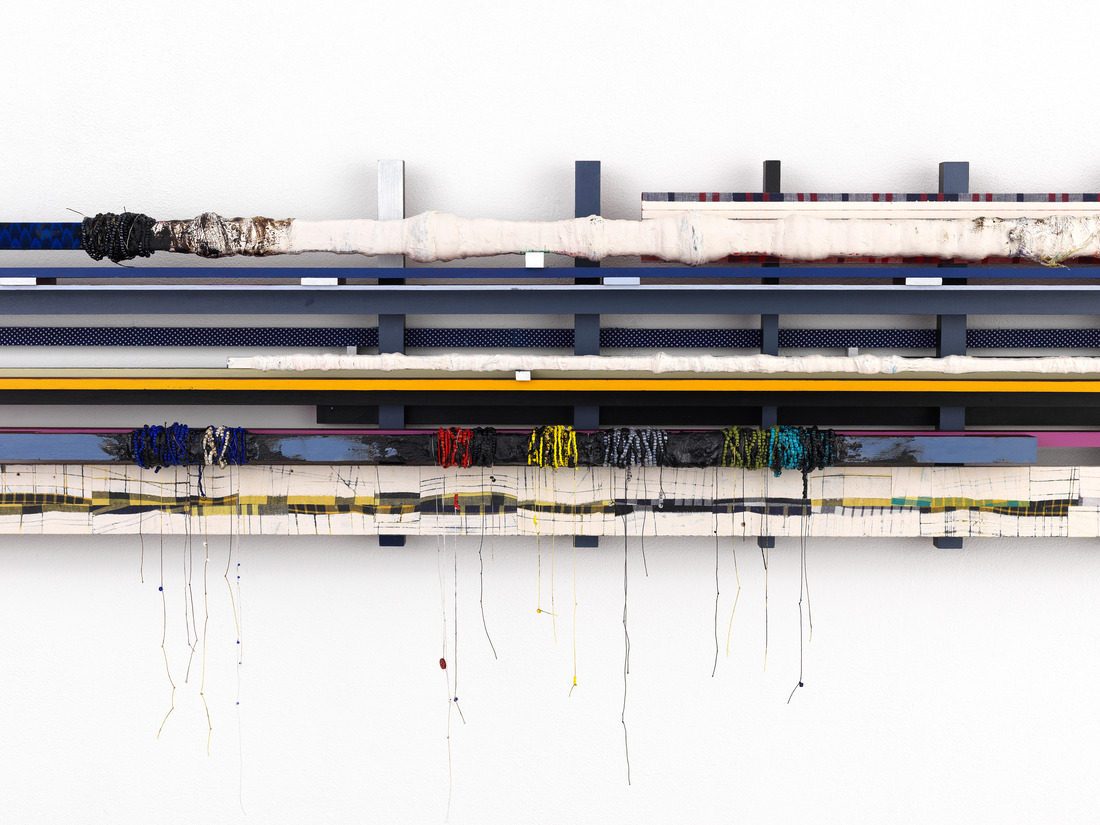

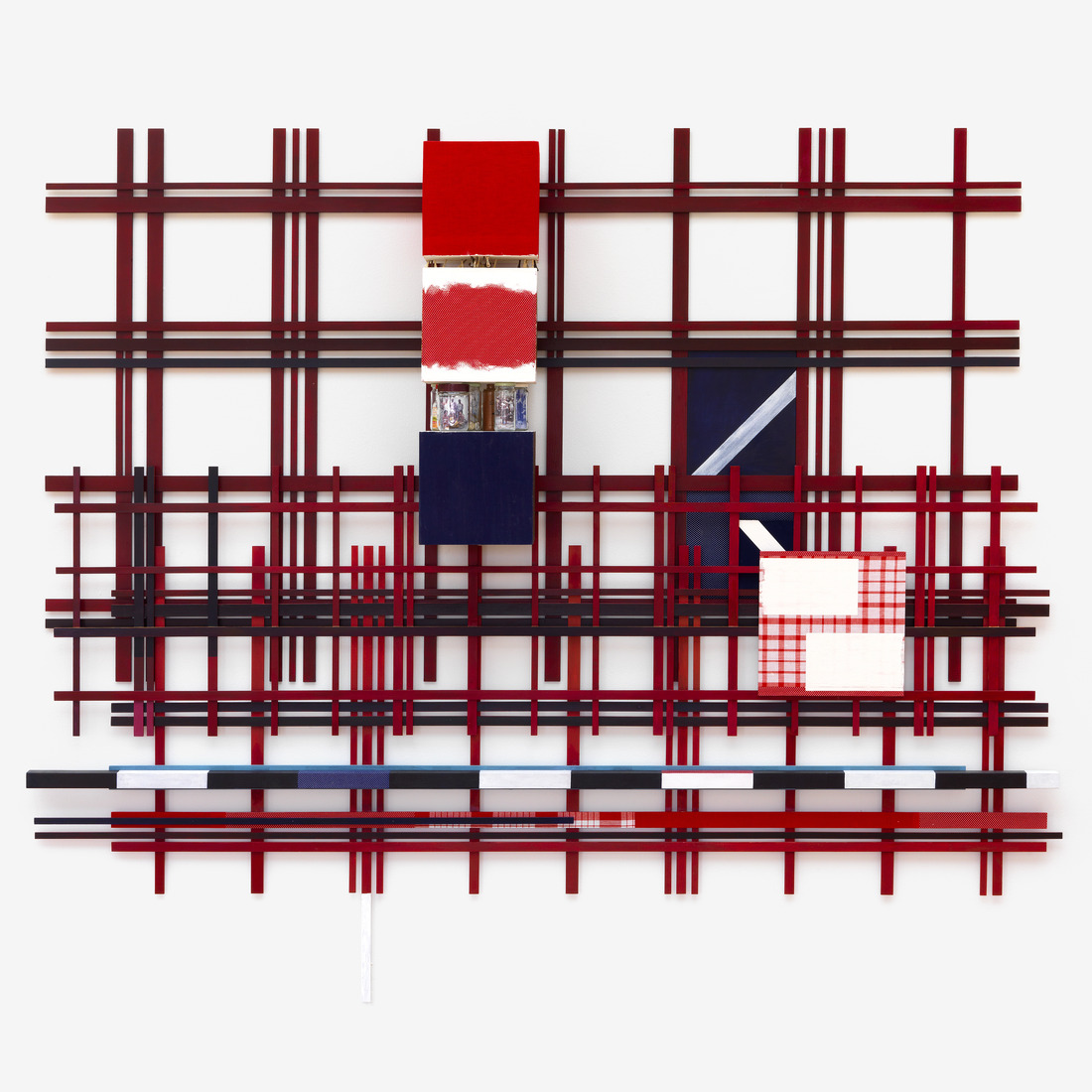

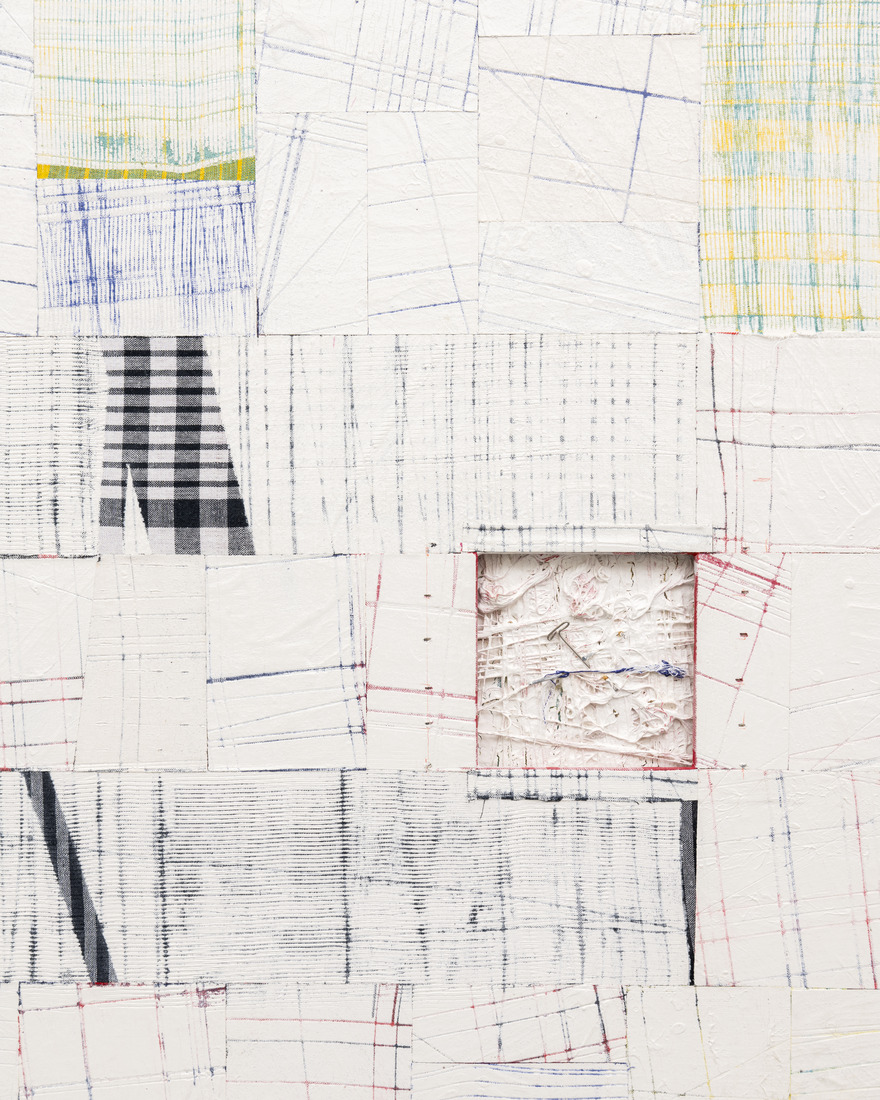

The materials in my work are related to those used in the ritual practices of the Afro-Surinamese religion, Winti. My main materials are textiles and mineral clay, kaolin. These gridded textiles are worn during Winti rituals to signify four different pantheons: water, air, forest, and earth. For example, the blue and white gridded textile represents air, and the yellow and black textile represents the forest.

By using these materials, the act in the studio becomes a ritual act—the artworks, in a sense, exist as “leftovers” from the ritual act.

The intersection of different art forms is a recurring theme in your work. How do you interpret the dynamic interplay, especially when it comes to the relationship between painting and sculpture?

It’s interesting because people often refer to my panels as “paintings.” One of the things I love about Siddhartha Mitter’s New York Times review of my solo show at Fridman Gallery in New York City in 2021 is his bold statement:

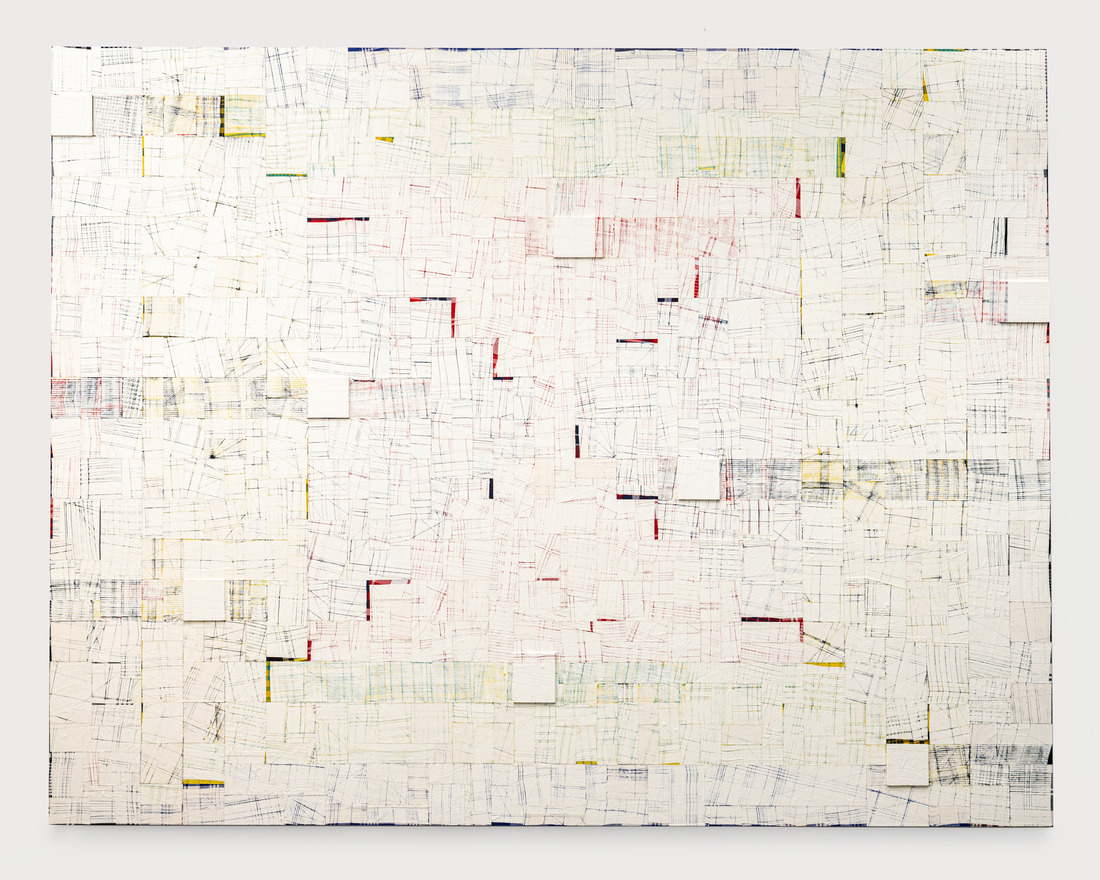

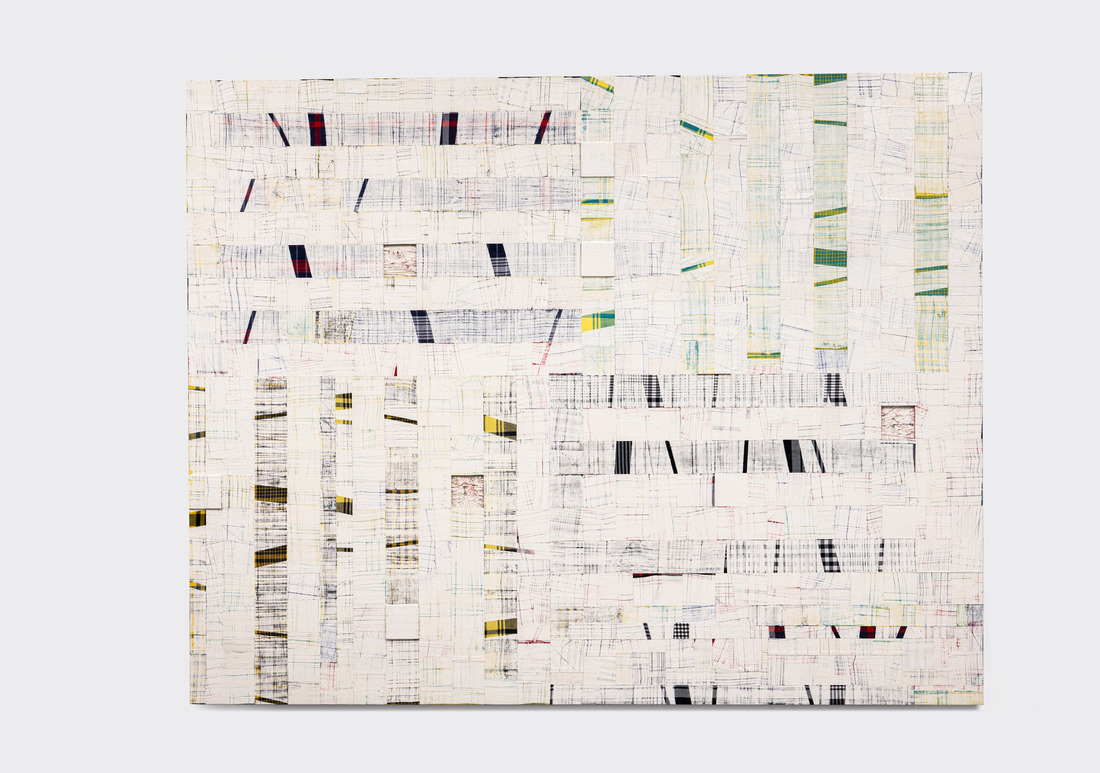

“Jungerman’s approach is now almost painterly—except that the panels on view in Brilliant Corners are not paintings; instead, they involve humble, plaid-like fabric that the artist glues to a wood board, then coats with white kaolin clay before cutting lines that reveal slices of the color beneath.”

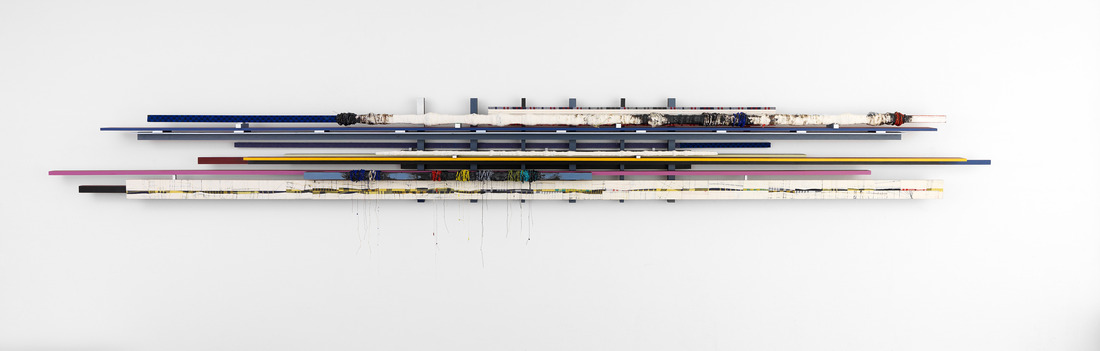

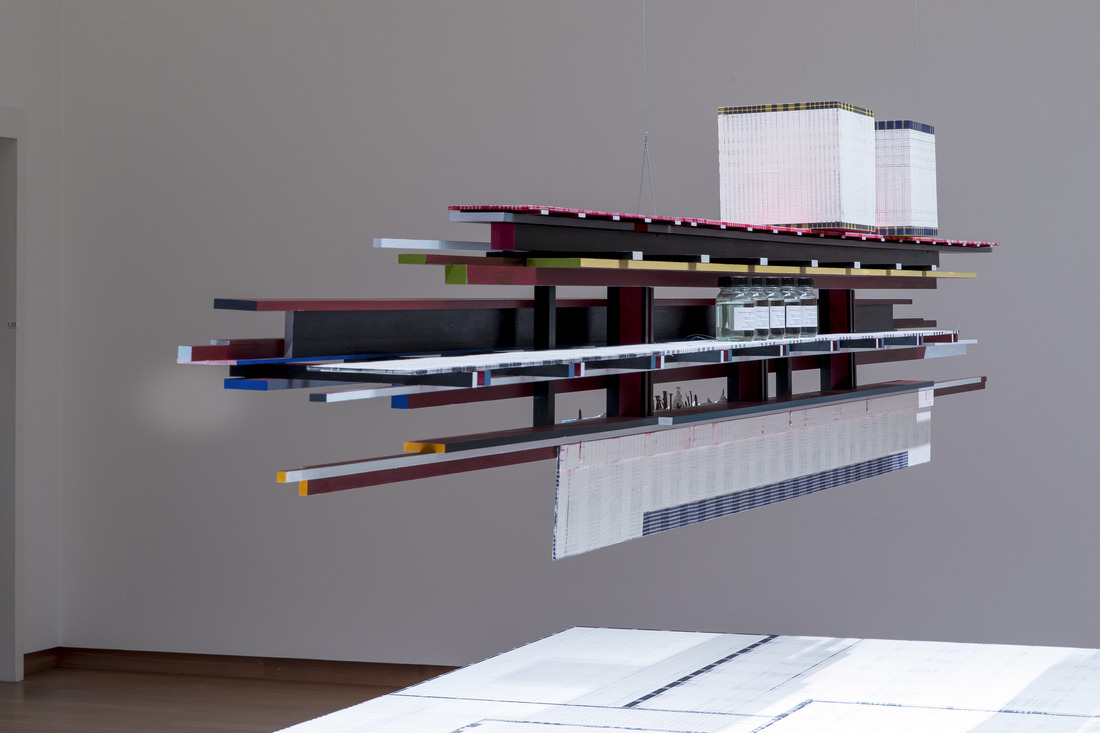

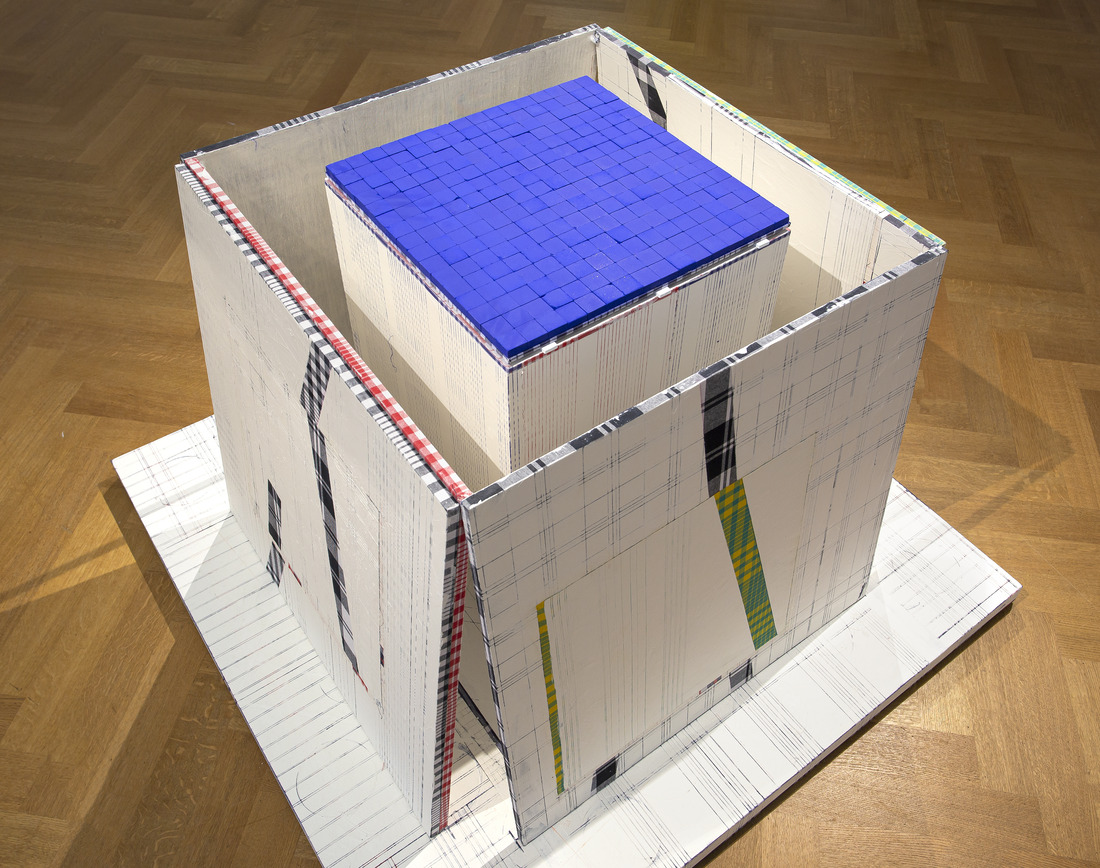

Indeed, the wall panels I create are not paintings. They have more of a sculptural approach. Yet, they blur the lines. I am “painterly,” except I use clay instead of paint. I apply textile. The way that I then carve lines into the surface, creating layers, can be seen as sculptural. As for my 3-D works—the floor pieces, often composed of cubes, and the horizontal and vertical wall pieces I create with pieces of wood and textiles, sometimes adding bottles, beads, and nails—are hung on the wall, but they are also quite sculptural. So, I see my work as continuously blurring the lines between “painting” and “sculpture.”

Your work addresses issues of migration and diaspora. How do you use art as a means to comment on the contemporary global migration crisis?

In my art, I don’t attempt to comment directly on the contemporary global migration crisis. However, I explore throughout history how the migration of people has ultimately enriched the world. If we examine the development of art in different movements in the past, it all traces back to the movement of people. The migration of people from one place to another has enriched cultures worldwide. The diaspora of African people began tragically with the transatlantic slave trade, but it has contributed immensely to the world in terms of important art and culture. Despite the tragedy, a dialogue between disparate cultures was formed and has endured.

As an example of how I have commented on migration, a large-scale installation I created for the Dutch Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019, titled Visiting Deities, quite literally establishes a space—a table—where different groups of people, including ancestors from the Netherlands, Suriname, Indonesia, and other groups impacted by the Dutch slave trade, can sit together and converge their stories. The table rests upon a dry seabed, a space where the untold stories of those who did not survive their journeys still rest on the ocean floor.

Could you elaborate on the significance of borders and boundaries in your art and how they relate to societal divisions?

Regarding borders and boundaries, the grid has always played a prominent role in my work, but its significance has shifted and evolved over the years. As a Surinamese Dutch artist, the obvious connection to Mondrian and De Stijl is present, considering I have lived in Amsterdam for more than half of my life, where I’ve absorbed its rich history. The grid conveys borders and boundaries, but its meaning can vary depending on the context. The way I have come to approach the grid has, in a sense, brought me full circle in my life and as an artist.

In recent years, I have been exploring how the grid has been used to map and restrict the movement of people and culture. For instance, plantations in Suriname and around the world were designed on a grid, enabling plantation owners to restrict the movement of people, and control and manage their creativity, culture, and spirit. Despite these restrictions, these people managed to maintain their culture in underground ways—a rich tradition that is still very much alive today.

Many artists struggle with evolving their style while staying true to their core vision. How do you manage to innovate your work while maintaining your unique artistic voice?

Maintaining your unique artistic voice takes time and patience. It’s a slow process! The pressures of earning a living can be a real obstacle. You see artists struggling and rushing into the creation of a style with commercial considerations in mind, but in my experience, this often fails. You need to slowly build the layers of your practice, always staying true to your core vision. There is a famous David Hammons quote that I try to live by: “I listened to rhythm and blues for many years to understand the abstraction in it. You can’t understand these things just because it’s hip; it took me a long time to understand free jazz, a very long time, and it was life, the process.”

How do you approach the relationship between art and spirituality in your work, particularly in the pieces you refer to as “Altars”?

I consider my artistic forebears to be my ancestors. They are constantly whispering forms and attitudes in my ear, encouraging me to explore and rhythmically interweave their collective knowledge into my artworks. By using materials related to ritual practices from my Afro-Surinamese religion, Winti, the works function as altars. Altars are interactive spaces that invite people to participate in the artwork. As I create these pieces in the studio—tearing textiles into small pieces, rubbing clay over the textile, pouring layers of liquid kaolin, and carving on the surface of the clay—I am establishing spaces that I hope viewers will engage with on a spiritual level, feeling the hands that made the works—the hands of both myself and my ancestors.

Can you describe the emotional and intellectual response you hope viewers experience when engaging with your art?

I was moved by the very personal responses to my solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from 2021 to 2022. I felt a genuine engagement with the idea of culture as something that can travel and stay with you, even as you absorb cultures not your own. When I arrived at the museum to install the works, there were security guards of Surinamese descent who worked at the museum, and they were very happy and proud to see my work on display. Throughout the installation process, they would stop by to ask me questions and share their impressions. A woman wrote a lovely note that particularly stays with me: “Thank you for the great exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum. Being a half-Surinamese, half-Dutch person born in the Netherlands, [the exhibition] has irrevocably unleashed something in me. Your film inspired a lot of healing in me. Your art has given me a deeper insight into an inner conflict I was unaware of. I feel that I now understand my culture better, and I feel more connected to it.” These reactions to my work–I hear versions of them in many countries and from different people who have experienced migration and or just the shifting sands of cultural identity–inspire me. It gives me hope that beyond all the “othering” in the world, there is some kind of shared language. This is what I hope to create in my work: a shared language.

Are there any upcoming projects or exhibitions that you’re particularly excited about and would like to share with your audience?

This year, I will have my first solo show on the African continent. Still Waters opens on May 2, 2024, at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, South Africa. I see this moment as an opportunity to connect to my source as a member of the African Diaspora, and to express gratitude for visual traditions that have enriched my practice so deeply.

In September 2024, I will have a solo exhibition at Galerie Ron Mandos in Amsterdam, where I will also launch a book titled Tracing the Lines. In this book, I tell the story of how the patterns and shapes seen in Surinamese Maroon shoulder capes and the Gee’s Bend quilts of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, mirror my work, as well as the larger narrative of how these patterns and shapes traveled from Africa to the Americas in the transatlantic slave trade. A major focus of the book will be on how I use quilt-making in my work as a literal process to unite disparate elements from the African diaspora.

Photo credit: © Remy Jungerman studio

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

More images: