Artist’s Biography

Rachel Kneebone is a contemporary British artist whose exquisite porcelain sculptures serve as a profound exploration of the human condition. Her works are an embodiment of the complex interplay between the physical body, renewal, and the ever-shifting dynamics of existence. With a primary focus on sculpture, Kneebone’s chosen medium, porcelain, invites unpredictability and a delicate dance with chance.

Kneebone’s artistic journey commenced around 2002, driven by her fascination with porcelain’s bone-white essence, a symbol of nascent neutrality. She pushes the boundaries of this medium, forging a unique bond between artist and material, embracing both control and the unexpected outcomes of the kiln. This dynamic dialogue results in sculptures that capture the essence of movement, time’s passage etched in cracks and fissures.

Her sculptures inhabit a realm between the conscious and subconscious, offering viewers a glimpse into an alternate reality. Densely worked forms emerge from undulating clay masses, blurring the lines between reality and imagination, between stillness and motion. Illuminated by a clear gloss glaze, her sculptures play with light and shadow, embodying the tension of positive and negative forms, motion and serenity.

Kneebone’s work takes inspiration from the annals of art history, drawing motifs and themes from old master paintings and classical sculptures. She weaves narratives, creating otherworldly spaces and times, exploring emotions such as hope, longing, loss, and suffering. Her ‘Raft of the Medusa’ series, for example, delves into the human experience, juxtaposing hope and despair, birth and death.

Renowned for her sculptural choreography, Kneebone draws parallels between her art and dance, seeing both as parallel universes that explore the essence of inhabiting a body. Her collaboration with choreographer T.C. Howard in ‘The Dance Project’ exemplifies this synergy, where the physicality of dance is echoed in her sculptures.

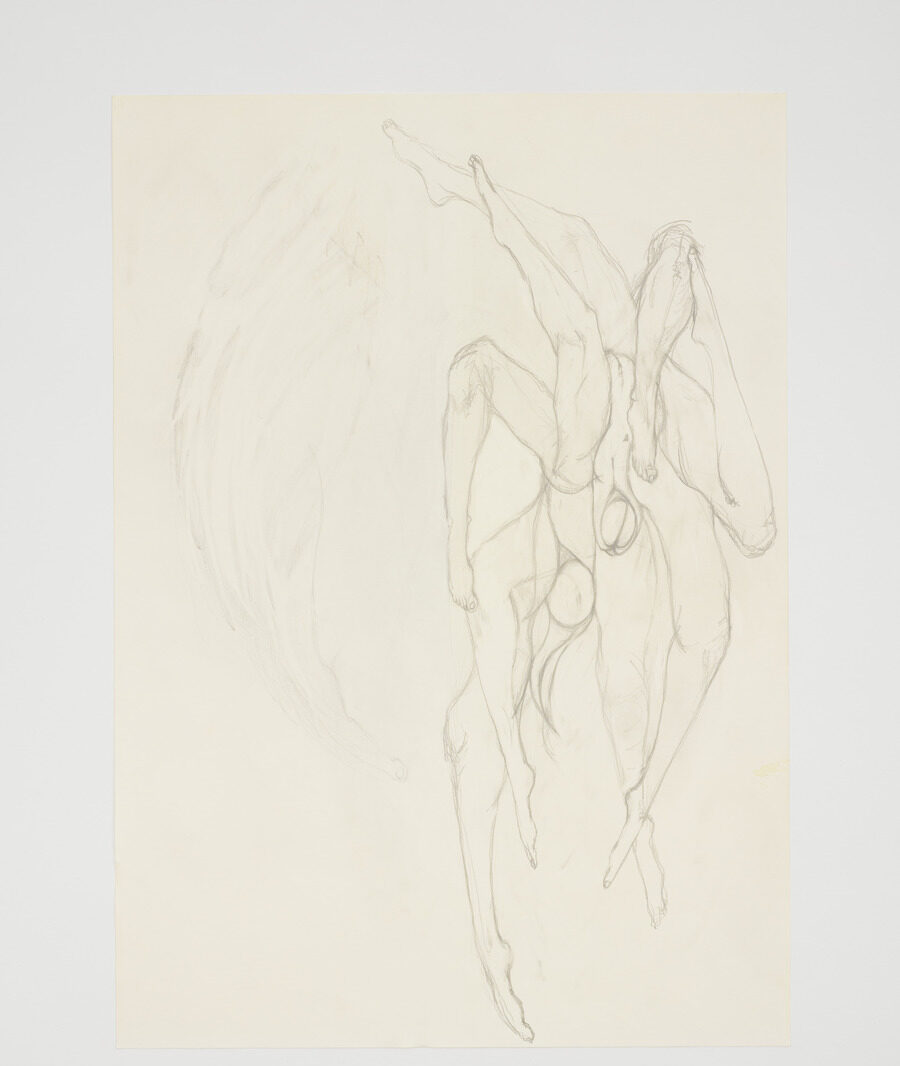

In her drawings, Kneebone continues her exploration of the human condition, creating and erasing partial, interconnected figurative forms that evolve as she rotates the paper. It’s a dynamic process that blurs boundaries and suggests new forms, akin to the fluidity found in her sculptures.

Born in 1973 in Oxfordshire, Rachel Kneebone lives and works in London. Her work has been exhibited in prestigious institutions worldwide, including the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Royal Academy of Arts. Her sculptures invite viewers on a journey through the intricacies of the human experience, offering a unique perspective on life’s perpetual ebb and flow.

An Interview with Rachel Kneebone

By Carol Real

You graduated with a First Class BA degree in 1997 and later pursued an MA in sculpture. Could you please share how your education influenced your artistic journey?

I first began working with clay when I was eleven years old while I was in school, and that marked the beginning of my artistic journey. During my B.A., I learned various clay techniques, including throwing, hand building, glaze mixing, and gained an understanding of ceramic processes. I created a wide range of forms during this time. While I had found my preferred material, I hadn’t yet discovered the right application. It felt like I was in the right area, but on the wrong path.

This is why I decided to pursue an M.A., as I wanted to explore a way of working that felt more natural to me. It was during my M.A. program that I began working with porcelain, and this coincided with the development of my current artistic practice.

How has living and working in London influenced your artistic sensibilities and choices?

London is a great place to live because there are so many things to see and do. Equally, it is a great place to do nothing–you never feel disconnected as you always know everything is continuing outside somewhere.

Do you have any rituals or practices that help you find inspiration when facing creative challenges?

Not really. It is very uncomfortable to experience a creative block. To fully embrace it is to genuinely believe that it’s the end, that you have exhausted all your ideas and there’s nothing left. It’s like a deep-rooted panic–what are you going to do now? Friends may tell you that it will pass and remind you of the last time you felt this way, and look at what you created afterward. Even Though you may resent them for downplaying the struggle, realizing that they don’t perceive how unique it is this time, that’s part of the process. Ultimately, for me, the answer has always been to keep working.

Your work was showcased in The Way We Work exhibition in 2005. How did this early exposure contribute to your artistic development?

That show at Camden Arts Centre was the second group exhibition I was included in after graduating from the Royal College of Art. These early exhibitions were great opportunities to experience the process of exhibiting work in institutions and galleries, as well as offering an exciting platform to show my work and dialogue with other artists. More generally, I guess it marked the beginning of showing my work to an audience.

In your early career, you created a wall sculpture for the Diana, Princess of Wales exhibition. How did this opportunity come about, and what did it mean to you as an artist?

I was invited to create artworks to accompany Mario Testino’s exhibition featuring the photographs he had taken of Princess Diana. The exhibition took place at Kensington Palace in London. I crafted a series of wall sculptures or sconces inspired by the architectural elements found in stately homes. To inform my work, I drew inspiration from Jean Cocteau’s film, “La Belle et la Bête.” These pieces exuded a sense of beauty and vulnerability that harmonized with the overall theme of the exhibition. This was my first commission, providing me with valuable insights and was a real learning experience.

Can you share the moment when you first felt a strong connection to porcelain as your preferred medium?

I started working with porcelain due to its whiteness, a decision based purely on aesthetics. I had no prior knowledge of how it would feel to work with. The connection I have with the material has been made over time; the experience of working with it has created the relationship. There was no one single moment of realization, more like a long and ongoing relationship with all the ups and downs that it suggests.

How do you push the boundaries of porcelain and embrace the unexpected in your creative process?

I create my work through the process of doing, and it leads the way. I don’t believe you can intentionally set out to push boundaries; that’s a byproduct of the ‘thing’ driving the work. The ceramic process has an uncontrollable aspect to it. The material undergoes changes and metamorphoses at each stage. Initially, porcelain is wet and pliable, allowing for hand modeling, but it dries before firing in the kiln. During firing, porcelain shrinks, leading to changes in the work that I cannot fully control. With experience, I can predict certain behaviors and encourage specific responses. This is what I embrace—the element of chance and the unpredictability of the outcome. As a general rule, what I place into the kiln is never exactly what emerges.

Your sculptures often depict the human body in intricate detail. What inspires you to explore the human experience through your art?

I believe that most people share an innate curiosity about what it means to be alive in this world, and we seek to express this experience through various creative outlets. For me, creating my artwork is my most profound way of contemplating and expressing this concept.

In my earlier works, I focused on sculpting legs and feet, drawn to their expressive qualities and their ability to symbolize movement, a recurring theme in all my creations. Movement is an integral part of life itself. In my more recent pieces, I’ve moved away from explicit narratives, and the forms and sculptures I create have become less literal. I believe this shift brings them closer to capturing the essence of the human body. To put it differently, my earlier work felt like an exploration from the outside, whereas my current work delves beneath the surface, seeking to understand what lies beneath the skin.

Could you elaborate on how the themes of transformation and renewal influence your work?

This connection relates to my interest in movement. When we observe movement, particularly the body in motion, we witness change and transformation. Time itself can be seen as a form of movement because over time, our bodies undergo transformation, sometimes even break down, but they still continue to offer us moments of renewal and reappropriation along the way.

Porcelain is typically associated with stillness and fragility, yet your sculptures often exude movement and fluidity. How do you achieve this contrast?

As I mentioned before, movement is inherent to the process of working with porcelain, the movement of the body to make the work, my hands, the movement of the material during the firing process. My interest in transformation and metamorphosis means that the form of the work is often in a state of flux. For example, a finely modeled surface adjacent to a rougher texture and then perhaps a more detailed form overlapping this. These different tensions in the work create movement, and when we look, our eyes travel and our bodies move around, interacting with the piece to explore it, to see as much of it as we can, despite the work being vitrified and still. The contrasting surfaces and form–the sphere, a length of vine, or twisting form–mean that the surface pulsates.

Could you please explain the significance of allowing your porcelain work to rupture and crack, with an emphasis on the relationship between strength and vulnerability?

The ruptures, cracks, and fissures within the work often result from the movement of the work in the kiln and the cooling process. These ruptures and breaks in the porcelain body serve as a form of punctuation; they are also the most intriguing aspects to me. They represent the gaps between things, moments when something is no longer what it was, but not yet what it will become. These tiny spaces are where we find freedom, where we can reinvent, renew, and begin anew. The moments of loss should not be feared; the work carries these breaks inscribed upon it, yet it remains strong and beautiful, much like how our losses and breaks are inscribed upon our human bodies.

Many of your sculptures incorporate recumbent limbs and floral forms. What do these elements symbolize in your art?

The forms in my work often have multiple “meanings” depending on who is looking at the work and what they see. However, as an example, the sphere in the work can be an eye, an egg, the world, a ball, the moon, bubble, mortality, or movement. The rose within the work is a rose, but it can also be seen to represent (in reference to Rilke) a model of life and death, or beauty wrapped around nothing, a void. The vines can be organic; they can also be of the body, umbilical, intestines, a skipping rope, a tether, or a way to come undone.

There is no dictionary of forms and their meaning; meanings are always varied and can and do change over time and, of course, for the individual looking at them.

How does the interplay of light and shadow on your sculptures enhance their meaning and impact?

As well as light and shadow, I think there is a third quality in motion here which is the works’ whiteness. The glossy white surface of the porcelain serves as a surface for light to bounce off and also to dissolve form. The shadows add depth, making the work have a kind of shifting dimensionality as well as serving as signposts toward the hidden unseeable areas within the work.

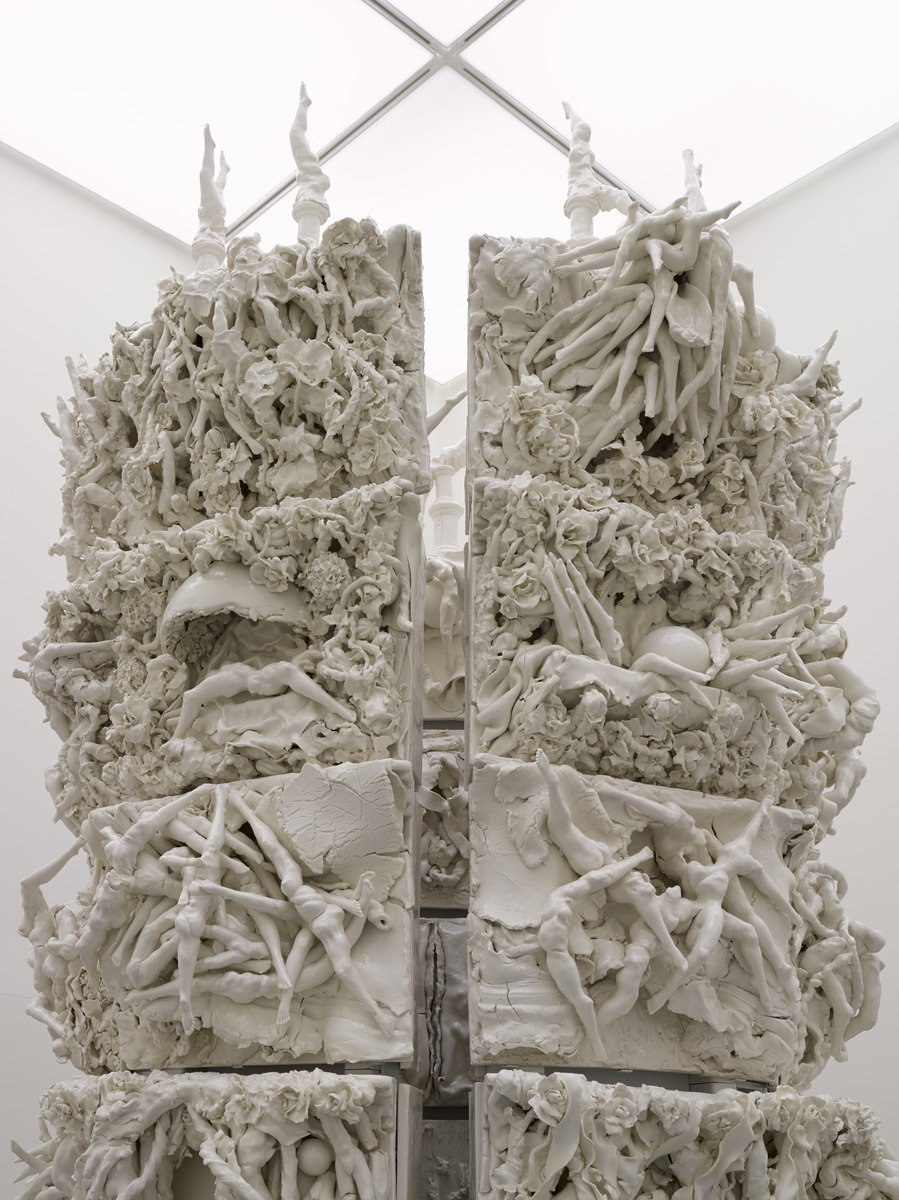

In your “Raft of the Medusa” series you draw inspiration from Théodore Géricault’s painting. How does your work relate to the arc of human life?

I don’t consider my works as interpretations. They are more like a way of entering the same room but through a different door. Géricault’s painting belongs to a specific moment in history, yet it addresses many issues that are still relevant today—feelings of hope and despair, people cast out and lost at sea, which of course evokes today’s refugee crisis. It’s more of a continuation or an attempt at a renewal of what matters: a quest for survival in the bleakest conditions. The series of sculptures also share some structural elements with the painting, in terms of composition and the geometry of horizontals and verticals, the movement of the wind and sea, and the upward thrust of a limb countering the downward slump of forms against the raft-like structure.

Stories and narratives play an essential role in your work. Can you discuss how storytelling influences your art?

All we have are our stories and how we interpret our lives. Stories and myths provide a means to explore different ways of being. They transport us to different times, places, and experiences that we can either relate to or reject. Through stories, we can discover new ways to understand our own lives and find new words to describe feelings we didn’t even know could be expressed in that way, even if the emotions are familiar to us. Stories are a vast resource for living. While we may have only one body, through myth, the world expands, and we can become many different creatures. Stories and myths have the power to transform the world. They serve as a shortcut to accessing various states of being.

Your work has been described as “sculptural choreography.” How do you connect dance and sculpting, and what does it bring to your art?

Creating, much like dancing, is a form of non-verbal communication. I believe it is just as valid as spoken or written forms of expression when it comes to exploring and reflecting on the essence of life. In many ways, it is even closer to our feelings, as it is a more immediate response from the body. Verbal language often confines us to specific meanings, whereas the movement of the body in dance or in the act of creating, as well as within the resulting artwork, possesses a sense of openness. This ambiguity allows for a broader range of interpretations and, consequently, a richer spectrum of meaning.

Works like Rib and Shell appear almost free-form. What motivated you to remove support bases and let the clay act on its own?

Both of the mentioned works have a different relationship with gravity, weight, and weightlessness; they are not located on a plinth and grounded in that way. While Rib is set against a wall, it feels as if it’s moving across it rather than being attached to it. Shell is suspended and carries a different tension; it neither falls nor floats but is suspended in time, like a vapor.

How do you balance control and spontaneity in your sculpting process when creating such dynamic and kinetic pieces?

I believe it’s about the act of creating itself. There’s a certain thoughtlessness that comes into play when relying on other senses to make decisions. Porcelain, in particular, is “time critical” as it hardens when exposed to air for too long, which can be both a challenge and an advantage. Working at a certain pace means you can’t meticulously plan every single detail; you establish the core structure or key components, and the rest is shaped by chance.

The more you observe, the more you discover–different relationships within the work can be perceived depending on your viewpoint and your emotional state at the time. The act of making art also resembles a series of problem-solving moments: as you work, each action uncovers new aspects that need to be addressed and balanced. This is the dynamism of the creative process, embracing the fleeting nature of the moment.

I do have control over the material thanks to my prior experience, allowing me to predict to some extent how it will behave. I understand enough about what will happen during firing in the kiln to shape the form in a way that anticipates how the porcelain will respond. However, there’s still an element of unpredictability and chance. To achieve the right balance, you must have a solid grasp of the material and enough control to be willing to let go and welcome spontaneity into the creative process.

Your drawings are created alongside your sculptures. How do they complement and inform your sculptural work?

The drawing I do is separate from making my sculptures. I do not draw and then use it as any form of a map for the work; that would be too restrictive. When making sculptures, you need to respond to what is happening in that moment rather than trying to copy a drawing. Besides, even if I found it possible, it would not be interesting to do.

There is an overlap in how I make sculpture and how I draw. As you mentioned rotating the paper, I also rotate the sculpture. It is built on a turntable, or I move myself around it to find new forms by looking from different perspectives. I believe that I erase marks in equal proportion to how many I draw, and this, too, is sculptural as it involves cutting off and adding on, the creation of positive and negative spaces. I also overlay forms when drawing and then erase lines to build new forms, composites from the ones before, just as I may leave the trace of a pre-existing mark from its impression on the paper, almost like a ghost of a form or a memory.

How does your broader vision align with your artistic approach that seems to blur boundaries and generate new forms in your drawings?

I believe this concept also resonates with my interest in dance, particularly ensemble dances. When you slightly adjust your focus or squint while observing a group, you can begin to construct novel forms from those in front of you. This act of looking requires active engagement, rather than passivity. We have the ability to seek out and create anew, although I’m not entirely certain whether these are genuinely new ways of perception or simply alternative ones. Nevertheless, this may correspond with “new” methods of artistic work and creation.

You’ve had numerous solo exhibitions worldwide. Is there a particular exhibition that stands out as a pivotal moment in your career?

All the exhibitions I have done have been pivotal in their own distinct ways. In a unifying sense, every time my work is shown in a different context, it changes due to the relationships that are built, whether with other works, group shows, duo shows, or with the architecture of the space or the landscape. The opportunity to exhibit internationally and to experience my work in different cultures with different languages and traditions has also been inspiring. It’s fascinating how we establish connections between “other” styles and spaces and how the work can serve as a bridge to make these connections across time and place. It allows me to perceive my work differently, in ways I could not have envisioned or created on my own. I see opportunities to showcase my work as a form of collaboration with the curators and the public. I have always taken responsibility for my work, but I have never claimed any authority over its meaning. This “openness” of the work creates spaces within it, enabling it to be reinterpreted and continue, rather than being completed, in new situations.

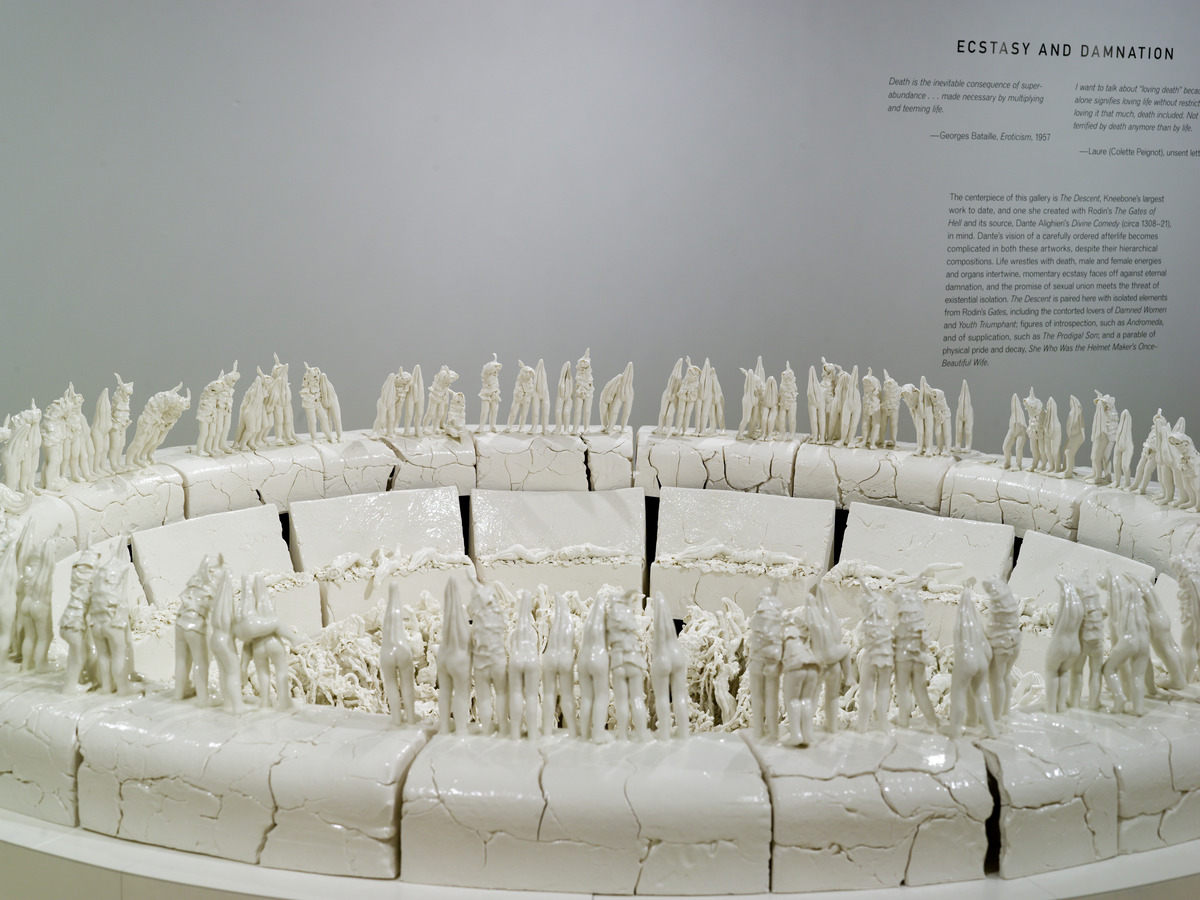

How did the Regarding Rodin exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum influence your perspective on your own work and the legacy of Auguste Rodin?

The Regarding Rodin exhibition was and remains a profoundly significant moment in my career. I will always cherish it. I was honored when Catherine Morris, the brilliant curator, asked me to showcase my works alongside those of Auguste Rodin in 2012, which was relatively early in my career.

Leading up to the exhibition, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of trepidation. I wondered how presenting my work alongside Rodin’s monumental bronzes would impact my own creations. It never crossed my mind that my work could change Rodin’s legacy; it was always about how his presence would influence mine.

One of the intriguing dialogues that Catherine Morris fostered across time in this exhibition centered around the hand—the transition from an initially clay form to a more refined bronze cast. Both our works shared this transformation, adding a new immediacy to the inherent austerity of bronze. The exhibition highlighted the concept of scale, emphasizing that it’s distinct from size. It revealed how artworks can swell and fill the surrounding space.

Moreover, it made me realize that all artists are inherently contemporary; it’s only time that separates us. There are universal human concerns that connect us across different eras. I had the opportunity to spend a couple of days as a guide in the galleries during the show, a new experience for me. It involved answering questions about the works and spontaneously crafting responses. Meeting visitors to the exhibition, engaging in discussions with them, and responding to their queries was a truly amazing experience.

399 Days was displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Could you please share the symbolism and significance of this monumental porcelain tower?

It was a great honor to showcase 399 Days in the Renaissance galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The artwork was positioned in close proximity to figurative sculptures and architectural forms, creating connections through form and scale while also challenging formal comparisons simultaneously. I believe the work was revitalized by its proximity to other pieces. It both resembled them and yet appeared alien in their presence.

The rupture that spans the length of 399 Days also symbolized the absence or fragility of the monumental, always susceptible to collapse and decay.

Porcelain is a delicate material, yet it is used to craft intricate and often powerful sculptures. What challenges and rewards accompany working with porcelain?

Porcelain has a reputation for being employed in fine, detailed wares. However, it is more than these associations; it can also be rough, heavy, unattractive, and substantial. I find these contrasts fascinating. As a material, it is brimming with possibilities. When I first started working with porcelain, I had no prior knowledge of it, so my lack of expertise allowed me the freedom to simply use it without a specific set of expectations. As mentioned earlier, I was drawn to it because of its whiteness. Working with porcelain is a form of collaboration, as it is not passive; within the material, there is resistance and an unwillingness to conform to my will. It is precisely this tension that I can harness and challenge to create my artwork.

Your sculptures are renowned for blending organic forms with human body parts. What motivates your fascination with this fusion?

I think it’s about how things are – simple as that. How we are all in a process of change and transformation. There is very little that is static about a body – at best we pause, but we never stop until death. We stop living, but as a body, we keep moving as we decay, rot, and putrefy.

Can you discuss the erotic and mythological themes present in your art and how they connect with your audience?

I don’t have direct control over how my work resonates with its audience, and I prefer not to try and manipulate that. My creative process draws inspiration from various sources, including mythology, storytelling, paintings, and the aspects of human existence, including our erotic nature, as expressed in dance, TV, films, conversations with friends, gestures, and interactions with the natural world, among others. My role in creating art is to capture those moments when these elements converge, freezing them in time.

The artwork takes on a life of its own during the creative process, influenced by chance and other factors beyond my control. The materials themselves, their response to heat during the kiln process, and the resulting ruptures and fissures all contribute to the audience’s experience. This interaction with the art may touch upon the sensory experience of the human body, but the exact manner and impact are always unpredictable.

Your work has been described as celebrating transgression, beauty, and seduction. How do you hope your art contributes to the contemporary art field?

I don’t have any aspirations in this regard. I create my work, and what matters to me is just to maintain my focus.

What role does art play in addressing complex and timeless themes, such as desire and emotional strength?

I think all art is contemporary–it’s just made at different times. The value of art, whether it’s in the form of sculpture, painting, music, dance, or any other medium, lies in its ability to ask questions and explore what it means to be alive in the world, and this aspect of art is timeless.

How did this installation enhance the narrative and experience of the museum’s Basic Instincts exhibition?

The exhibition was concurrent with the Basic Instincts exhibition, featuring works by Joseph Highmore, a Governor of the Foundling Hospital. These works share a common interest in a woman’s body and her rights over it. Within the context of the Foundling Hospital, these rights are primarily reproductive rights. My series of works addresses issues of anguish and despair in the face of adversity and the hope that emerges from such circumstances. There are clear parallels between the despair and anguish experienced by those in a societal position where they must give up a child, and the hope that the child will be taken care of.

Could you please share any challenges you encountered when creating this series of porcelain sculptures?

One of the challenges was that people often mistook it for a literal translation of a painting.

Is there a specific international exhibition that has left a lasting impression on you or influenced your artistic perspective?

Returning to the discussion about the Rodin show, what stood out to me was the sense of a dialogue across time, and I have carried this with me. Additionally, the exhibition I had at the Serlachius Museum in Finland, titled Punoutua, was equally inspiring and evoked a desire to live under the vast sky.

Looking back at your earlier works and your recent creations, how do you perceive the evolution of your artistic style?

I don’t consider my work to have followed a linear path of evolution. Instead, it undergoes constant change. I believe the most significant shift occurred in 2017 when a piece I was firing collapsed in the kiln and took on a form beyond my control. It was at this moment that I realized I was limiting my art by attempting to exert complete control over every aspect of my creations, imposing a predefined narrative, and over-managing the material.

I came to understand that as a creator, it is far more intriguing to set the stage, release control, and allow the material to respond in its own unique way. However, achieving this level of artistic freedom requires a foundation of knowledge. This knowledge was acquired over time, as I learned how the material interacts with specific tools, how it transforms in the kiln, and the range of possibilities I could explore and create. Once I had this understanding, I was able to step back and become less dominant in the creative process while still being a catalyst for the art’s expression, if that clarifies my approach.

Has your perspective on the role of art in society and culture changed over the years?

No, I believe it’s a human compulsion to create.

Have there been any artists, either from the past or present, who have profoundly influenced your artistic journey?

In 2007, I attended a Louise Bourgeois retrospective at the Tate, and I was struck by the recurrence of her interests throughout her lifetime. Now, it may sound simplistic, but there’s often a fixation on the constant pursuit of new and innovative ideas and this notion of constant evolution and progression. I distinctly remember a moment of clarity when I realized that it’s not necessary to constantly explore a wide range of new and diverse interests. In reality, significant shifts can arise from revisiting and rejuvenating a single theme or motif. There are threads that weave through a lifetime, anchoring us, and in doing so, granting us freedom.

Could you share a memorable encounter or reaction from someone who interacted with your sculptures, one that deeply resonated with you?

It always matters when someone tells you that your work means something to them. However, I have this inbuilt protective device where I never remember what someone says. This doesn’t mean that I’m not grateful for their time spent with my work; it’s more about staying true to the work and not letting other perspectives shape it too much.

Are there any upcoming projects or collaborations that you are excited to share with us?

I am currently working on a commission that has given me the opportunity to explore ideas of suspension, weight/weightlessness, gravity, and the body. I’m really enthusiastic about it.

How do you envision your art evolving in the coming years, both in terms of themes and techniques?

I have no idea. I will keep making and see what comes out.

What advice would you offer emerging artists who aspire to push the boundaries of their chosen medium and make a meaningful impact through their art?

I don’t really feel qualified to provide advice as I’m still exploring my own path, but for me, the key has been to concentrate on the work and remain dedicated to it.

Lastly, what motivates you to continue exploring the possibilities of porcelain and the human form in your art, and where do you envision your artistic journey leading you in the future?

It’s an intriguing phenomenon to consider that the more you engage in a particular activity, especially one as seemingly simple as working with a single material, the narrower the possibilities might appear. One might assume that over time, there would be fewer unexplored avenues. However, my experience has shown me that the opposite is true. The more I delve into this artistic pursuit, the more I discover there is yet to explore. Experience both expands and refines my perspective.

In truth, we never truly arrive at the future; it remains an ongoing journey. My aspiration is to continue creating my work, to persist in this artistic path and keep moving forward.

Photo credit: © Courtesy of the artist, White Cube Gallery, and Brooklyn Museum

Editor: Kristen Evangelista