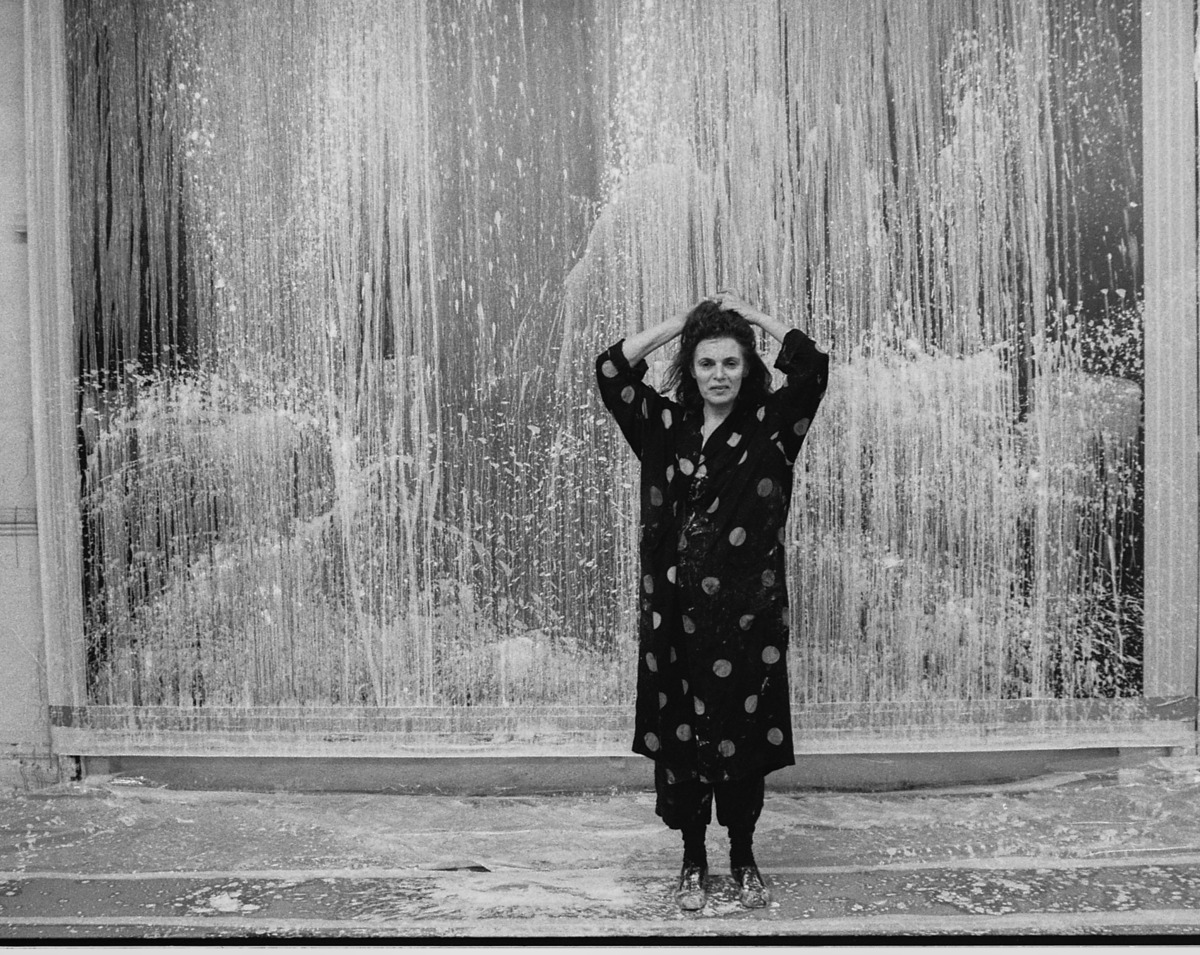

Among the great innovators of contemporary painting, Pat Steir first came to prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s for her iconographic canvases and immersive wall drawings. By the late 1980s, her inventive approach to painting—the rigorous pouring technique seen in her Waterfall works, in which she harnessed the forces of gravity and gesture to achieve works of astonishing lyricism—attracted substantial critical acclaim. Informed by a deep engagement with art history and Eastern philosophy, and a passion for artistic advocacy in the both the visual and literary realms, Steir’s storied five-decade career continues to reach new heights through an intrepid commitment to material exploration and experimentation.

Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1938, Steir attended New York’s Pratt Institute from 1956-58, where she took painting classes from Richard Linder and Philip Guston. Steir transferred to Boston University College of Fine Arts where she studied art and philosophy from 1958-60, before returning to Pratt, where she received her BFA in 1962. It was during her days as a student that she first became acquainted with many of the most influential conceptual and minimalist artists of the day, figures that would become Steir’s lifelong friends such as Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden and Lawrence Weiner. Shortly after graduating, Steir was invited to participate in her first group exhibition at The High Museum in Atlanta and only a year later was featured in group shows at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and The Museum of Modern Art, New York. These shows helped position her among the first group of women artists to gain recognition in the male dominated art scene of the time, paving the way for numerous long-term relationships with well-respected international galleries. In the mid-1960s, Steir worked as a freelance illustrator before being offered the role of Art Director at Harper and Row Publishing Company in New York. In the early 1970s she taught illustration at Parsons the New School for Design and then painting at the California Institute of the Arts where Ross Bleckner and David Salle were among her students. Steir simultaneously worked as an editor for Semiotext(e) magazine and was a founding board member of both the Printed Matter bookshop and the landmark feminist journal Heresies.

Steir also became friends with artists Mary Heilmann and Joan Jonas in the early 1970s, participating in an early improvisational film by Jonas and joining Heilmann and artist Joan Snyder in a three-person exhibition at the Paley & Lowe gallery. It was also during this time, at the invitation of Douglas Crimp, that Steir first travelled to New Mexico to visit artist Agnes Martin, a trip she would continue to make over many years until Martin’s death in 2004.

In the mid-1970s Steir showed her first iconic and critically acclaimed series of works—paintings of roses that were then completely crossed out, transcending the divide between figuration and abstraction. She also began to make site-specific wall drawings and room-sized installations. These installations transformed her paintings into a three-dimensional experience formed by light and line, allowing the viewer to step out of their reality and into an illusionary world connected to both nature and the progression of time. As Steir has said, ‘Installation allows the artist to paint out of the painting and into space and the viewer to move from space into a painting—the space where the act of painting takes place is in the imagination of the viewer.’

In the late 1970s, after traveling extensively both in the United States and in Europe, Steir and composer John Cage became good friends while working together at Crown Point Press. His embrace of chaos or randomness and non-intention in creative activity became especially influential on her practice, inspiring her to see new potential for accident and chance in artmaking. In the early 1980s, Steir made her first trip to Japan where she became fascinated by Japanese woodcuts and Chinese literati landscape painting, particularly ancient Chinese Shan shui (mountain water), which evoked nature rather than trying to replicate it. By the late 1980s, Steir began experimenting with the technique that has since come to define her oeuvre, no longer strictly using a brush which allowed her to take herself out of the picture. Subject to the influence of time, the finished work is what gravity and the weight of the paint has made. They are not paintings of landscapes but landscapes in and of themselves, an image that both evokes a waterfall and is a waterfall. As much as Steir’s process embraces chance, she retains complete command over the basic parameters. It is a harmonious collaboration between control and chaos, ‘chance within limitations.’ A remarkable synthesis of conceptualism, minimalism, and abstraction that challenges the postwar American canon, Steir’s practice remains limitless.

Source: Hauser & Wirth

An Interview with Pat Steir

By Carol Real

Can you share your earliest memories and reflect on the evolution of your work that has brought you to where you are today?

Well, my evolution took many, many steps. In the beginning, there were other women who started out with me, some are still working. However, for me, being one of the few women, and sometimes the only woman, among a predominantly male-dominated group, I viewed the challenges I faced as disturbances, something to brush aside rather than a central focus. Life presents many inconveniences. I noticed that the art world had a ratio of 120 men to one woman, and I regarded it as an inconvenience rather than the central issue.

Perhaps I miss out on some important aspects of life by perceiving significant things as inconveniences, but in another sense, I gain a lot by seeing things this way. Anyway, it’s my nature. It’s not a deliberate choice. It’s my natural tendency to view anything that interrupts my work as an inconvenience. Ever since I was a young child, I wanted to be an artist. That’s been my aspiration since I was five years old.

Five?

Yes, very early. I must’ve had the flu or something. My father brought me a little paint set, oil paints, and I painted the tree that I saw outside my window time and time again. And as I became an artist, painting the tree in the field.

Were they supportive of your decision to become an artist?

They were very worried. And they could see other things they would like me to be besides an artist, but I wanted to be an artist.

Your work has evolved significantly over the decades, from iconic canvases to your innovative pouring technique in the “Waterfall” series. Could you share your insights into the transformation of your artistic approach and the role of gravity and gesture in your later works?

The “Waterfall” paintings are easy to see, and not many take this approach. As you’ve pointed out, I transformed from abstract painting to creating a tangible image, from the abstract to the physical. This was my main objective. Unfortunately, not many people prioritize viewing the whole picture in this way, as our education system, especially in America, tends to neglect holistic thinking. It’s a shame to say, but our education is lacking, and individuals are not encouraged to incorporate the past into their thought processes.

And well, abstract painting is still ongoing, although I think it shouldn’t continue, not because it’s bad, it’s good, but is it speaking for this time? Something else needs to speak for this time.

Not my work either. My work represents the time that came before, creating the possibility of making abstract art tangible. That was my lifelong goal, and I achieved it. But now, something non-technical should happen, not created on computers or the internet. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? There is a whole generation of young artists searching for it. Some promising developments are occurring, along with some not-so-promising ones. And certainly, the political situation in this country is dire. Moreover, the political situation all over Europe and the Middle East feels like an end game, very frightening.

Do you think that art can help open hearts, improve communication, and bring about transformation?

It can, but there needs to be an audience ready for it. It can only achieve this with an audience. For instance, I was just speaking with my friend, the poet Anne Waldman, before you arrived. She strives to achieve that through her work and has a dedicated following.However, not everyone is educated enough to comprehend it. It requires a willingness to learn and understand.

Probably critical thinking is what is lacking in our society. We don’t always engage in genuine thinking; sometimes, we merely echo what others want us to believe, or we mindlessly follow the crowd.

The fact that so many people just follow is a result of the culture they’re brought up in, not their fault. They follow like good prisoners or good people.

John Cage’s embrace of randomness and non-intention influenced your practice. Could you share specific instances of how Cage’s ideas have shaped your artwork and creative process?

A lot. Very much. Well, I appreciate the idea of chaos in the creative process and letting go. As an example, I once mentioned to John, “I have two clocks, one my brother made and one I got at the store, and they each beat the minute, but they’re out of sync. They don’t beat it at the same time. And I would like to send you a recording of that.” And John responded, “I have that. I already have that.”

Control is exerted when you apply it to the canvas. Putting it on the canvas is the act of control. However, once it starts dripping or pouring down, I lose control because you can’t halt the flow of a pour and change its direction. You must allow it to follow its natural course, as you can’t reverse a pour once it has begun.

So, control is present in the initial brushstroke application. I learned that from John, and I also learned that John did some editing of his work. It wasn’t purely spontaneous. Sometimes it happened accidentally. My friend Veronica Gonzalez made a film featuring me, and she included some footage of John. He was making noise by clanging pots and pans on a TV show, and a teakettle went off. He wanted to shock and surprise everyone with his sounds. In a way, he didn’t fully control it, but he did have control in choosing the specific pots and pans to create the noise. Anyway, I was greatly influenced by him, and I admired his thinking. He was also influenced by Eastern philosophy.

Your interest in Japanese woodcuts and Chinese landscape painting played a significant role in your work. How did these artistic traditions resonate with you, and what aspects of them do you incorporate into your own practice?

Well, with Japanese woodcuts, it’s about control and releasing control, where the two aspects become one in the image they create. I find this aspect of control and letting go fascinating and it resonates with me. As for Chinese landscape painting, it’s a much deeper interest for me, and it’s challenging to explain my fascination with the poetry and painting from the Literati and Song dynasty period. There isn’t a historical relationship between me and these historical and spiritual traditions, but somehow I feel a close connection to them.

Your work frequently blurs the line between figuration and abstraction. How do you reconcile these two opposites?

It’s not that I don’t need to differentiate. I’m trying to show that the connection exists. Abstraction theoretically emerged in the ’50s, and we were proud to move away from the image. My painting, however, suggests that by simply using the iconic symbol of the dripping brushstroke, I can create an image. So, it’s meant to demonstrate the strong connection between the two.

Scaling a ladder and carefully pouring the paints can pose a considerable challenge, making your task inherently difficult.

No, I don’t. I have a lift, a cherry picker. I used to enjoy climbing up the ladder and standing on the ladder, but I don’t have to do that anymore. I enjoyed the fact that I could do it.

How do you approach the transformation of two-dimensional paintings into immersive three-dimensional pieces in your work? Could you discuss the relationship between the spatial aspects of your paintings and the way they engage the viewer’s imagination within these installations? It’s fascinating to observe your paintings taking on a new dimension.

Certainly. It’s almost indescribable. The three-dimensional aspect of my work, which gives the impression of marks moving away from the wall, has a profound connection to my painting. Elements like eyes, noses, and mouths are all borrowed from ancient drawings, specifically from Roman academics. These pieces reflect more of my interest in history rather than my interest in art, even though they are beautifully drawn. They are all created by talented young artists, typically recruited from local universities or museums wherever I happen to be.

What were the toughest challenges you had to face in establishing your place in the art world, and how did you overcome them?

I overcame them by ignoring them. I viewed them as inconveniences that needed to be overcome. I kept moving forward, like a little tractor mowing the grass. In the beginning, no one saw art as a career, and neither did I. I saw it more as a vocation than a career or a hobby.

The challenge was that I was searching for something that wasn’t in sync with my time, and it was difficult to pursue. However, that challenge began to reveal a clear path when I created the large Brueghel painting and conducted extensive research into the artistic practices of many artists. It was a turning point for me, granting me a sense of freedom. Through that painting and the research involved, I gained clarity on where to proceed.

That’s very significant, whether pursued as a vocation or a career. It’s likely the key to success because you genuinely love what you do.

Yes, exactly. And not only that, but it was the only thing I could do. It’s what I wanted to do. It’s what I could focus on. Often in my career, my work wasn’t beautiful or even desirable, but I went through stages like research, unsuccessful research, and unsuccessful research like that. I approached it more like a researcher and, in a way, more like a scientist than an artist. However, I wasn’t a scientist because I didn’t incorporate outside information.

What motivates you to keep working and continues to inspire you to experiment with and explore new materials?

Well, there’s always something else to ponder. My new paintings are inherently connected to the political world, responding to the ongoing wars and external events. They provide a subtle response to the outside world and offer unspoken answers. While I don’t explicitly address it in my work by saying, “This is about the terrible wars going on right now,” the impact of these events is undeniable, both on me and my work. I could attribute the work to specific themes, but I prefer to let it communicate silently.

Could you reflect on the impact you have had in promoting diversity and inclusivity in the art world?

I’m not entirely sure about the extent of my impact, but I can certainly share my perspective.

I don’t know what it is, but diversity and inclusivity are certainly a part of my life story. I’m not sure if my work promotes diversity in any way, but as a woman who has managed to thrive in the art world for 60 years, I believe I have contributed to the promotion of the good aspects of the art world that embrace diversity in all its forms. This isn’t about self-promotion; it’s a genuine belief.

Can you share any memories or experiences from your time as a teacher with some of your students, or perhaps something significant that you have learned from them, or that they have learned from you, given that you have been very influential to other people?

Yes. There are some students that I remember very well and still have friendships with. I always mention Ross Bleckner and David Salle as two who stand out. Another one is a woman, Kathleen McShane, who worked for me. Amy Sillman was a student and a studio assistant for me as well. So those people stand out in my memory. Some people I still see who were students of mine, but I don’t think of them as students. I think of them as very developed artists. Amy Sillman, in particular, stands out as a developed artist.

And then David Salle, he made a lot of inventions himself while learning from the inventions of others from the older generation. One can learn a lot by looking at his paintings.

You also formed very strong friendships with other prominent figures in the art world, such as Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, and Lawrence Weiner, right? Do you recall any experiences from those days?

Well, I met Brice when we were students, so I’ve known him for 62 years. I’m deeply saddened by his passing.

One experience from those days that I recall is one time I got in a little car and tried to drive from Boston to New York, but I ended up in Albany. I just remember that Brice enjoyed that. He enjoyed the news of me ending up in Albany. I also met Lawrence Weiner and his wife, Alice, in my early days in New York, and similarly, I met Sol early on in New York.

In the first years that I knew my husband, I used to visit Lawrence and Alice along with their daughter Kirsten on their boat frequently. There are two things Lawrence said that have stayed with me. He would always say, “Let’s go to the beach on Wednesday.” I would then make my way to their boat so I could ride with them to the beach. Every time we went, it was raining in Holland, and it was no different at the beach. We would buy French fries, which they called Belgian fries, and enjoy them in the car. I once asked Lawrence, “Why do you always invite me to the beach when it’s raining?” He replied, “I didn’t say we were going to swim. We had potatoes.” So, that was Lawrence.

When reflecting on individuals who have achieved notable careers like yours, what do you perceive as the shared characteristics that contribute to their success? Is it their personality traits, their unwavering determination, or something else entirely?

In Lawrence, it was a combination of a good idea and perseverance. Sol, on the other hand, was quite different. He was ahead of his art generation by about 10 years. He initially pursued abstract painting, but realized it wasn’t working for him. He then came up with the concept of conceptual art, and that idea worked perfectly for him and lasted his entire lifetime. It’s still influential even though he passed away about 12 years ago.

What advice do you have for emerging artists looking to make their mark in the art world?

Just cross your fingers and go ahead and work. Hope for the best.

You have received numerous awards and distinctions, like the International Medal of Art from the United States Department of State in 2017.

Well, it’s a pleasure. It was an unexpected pleasure.

Can you tell us more about your current project or upcoming exhibit?

I have a show opening in Los Angeles on the 28th of February at Hauser & Wirth Gallery.

That sounds exciting! Can you provide some details about what visitors can expect to see in your upcoming show?

There’s a model right here, along with new paintings. I’m pushing the boundaries of my existing work, and the model with the paintings is right behind me.

How do you envision the role of arts in society and culture in the years to come?

It’s a mystery because we now have AI, artificial intelligence, which worries me greatly. What it can do is simplify everything. Artificial intelligence can reduce poetry to meaninglessness and turn art into something ordinary. It might make art something you typically encounter, rather than something that genuinely surprises you.

If you were to reflect on your life and your career, would you change anything, or would you do everything exactly the same way you did it?

Well, given that I have no opportunity to change anything, I would do it just as I did it.

I believe that if you were given a second life, you wouldn’t remember this one; you would simply have a new life. So, you wouldn’t be able to make that decision again. You’d never have the chance to make that decision, whether to do things the same way or not. You’re either blessed or cursed to always do it the same way.

What are the things for which you feel grateful in life?

Oh, everything. I’m grateful to still be alive, for one. I’m thankful for everything I’ve learned, the people I’ve learned it from, and some who have learned alongside me. There’s a beautiful poem, “Ithaca,” by the poet Constantine Cavafy, which is about gratitude. It essentially conveys, “It’s not about what you acquire, but what you gain on the journey.”

But on the journey of life.

All images courtesy of the artist © Pat Steir Studio and Hauser & Wirth.

Interview conducted in January 2024 at the artist’s New York City studio.

Interviewer: Carol Real

Editor: Kristen Evangelista