For over four decades, Minoru Nomata has dedicated himself to crafting a mesmerizing vocabulary of ethereal architectural and topographical forms, transcending temporal and spatial constraints within his paintings. Born in Tokyo in 1955, Nomata’s artistic journey stands as a testament to his innate ability to create enigmatic, otherworldly realms that seamlessly blend the familiar with the mysterious.

Commencing his artistic odyssey with a foundation in design at the Tokyo University of Arts, Nomata explored advertising before fully immersing himself in painting in 1984. The pivotal moment in his artistic emergence came with a groundbreaking exhibition in 1986 at the Sagacho Exhibit Space, a pioneering alternative arts venue in Koto-ku, Tokyo, marking the onset of a prolific career.

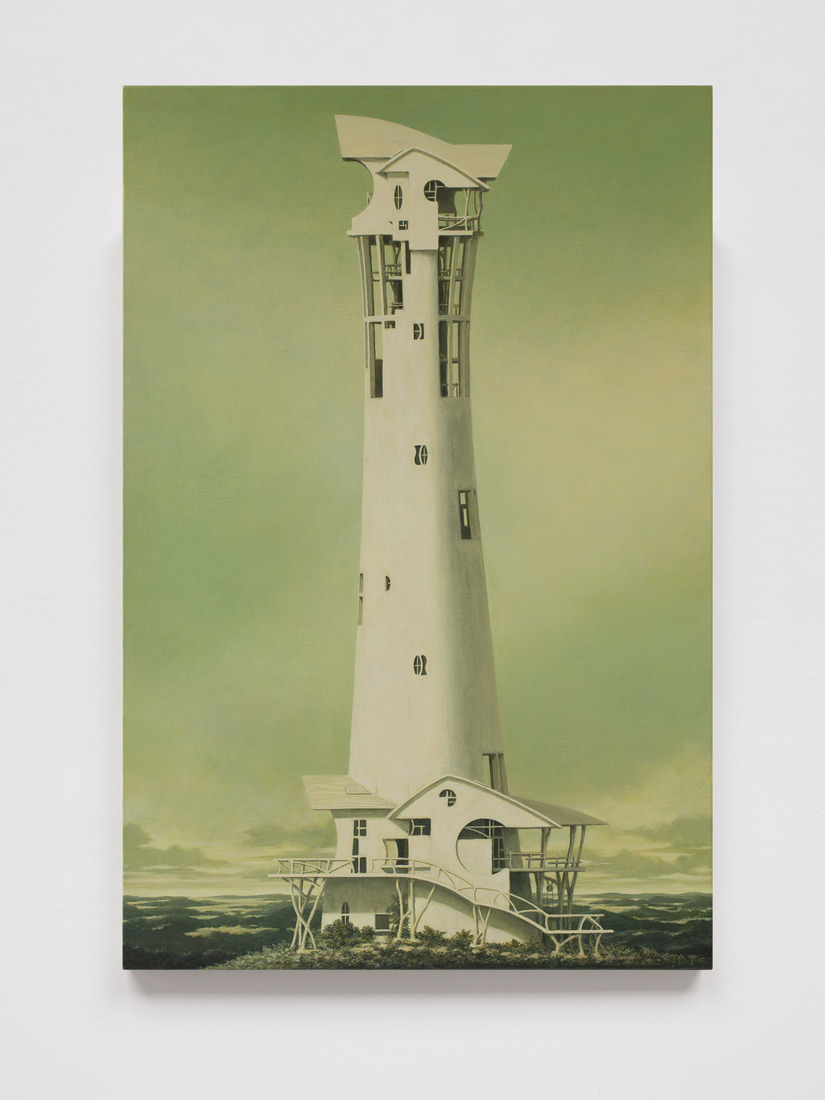

Drawing from a diverse array of influences, Nomata’s early works reflect Greek and Roman architecture, classical ruins, and motifs reminiscent of Medieval and Renaissance paintings. The ‘Decors’ series, originating in 1987, introduced distinctive architectural structures against a backdrop of sky and clouds, creating a surreal stage where narratives linger in the unseen.

Nomata’s artistic DNA intertwines references from various sources, including the ambient atmospheres of Brian Eno and Erik Satie’s music, the surreal paintings of Magritte and de Chirico, and the precisionist aesthetic of Charles Sheeler. Growing up in an industrial area of Meguro, Tokyo, Nomata’s aesthetic vision draws from the transient nature of urban surroundings, mirroring cycles of demolition and rebuilding, reflecting his personal journey.

As Nomata’s artistic narrative unfolds through the decades, his works evolve to incorporate wind turbines, greenhouses, and towering earthen forms. The ‘Bourou’ series from the 1990s emanates an eerie glow, while the ‘Windscape/Perspective’ series in the late 1990s and early 2000s introduces a sense of movement with archaic constructions defying gravity.

Nomata’s oeuvre delves into socio-ecological concerns, culminating in the ‘Light Structures’ and ‘Skyglow’ paintings from the 2000s. These works scrutinize the overabundance of electric light in urban environments, unveiling towering high-rises enveloped in darkness, illuminated by toxic hues. Nomata’s canvases serve as a visual commentary on the ambivalence of urban living and the impending crisis of climate change.

Residing and working in Tokyo, Nomata is influenced by generative electronic music and retro-futuristic science fiction as he creates intricate yet vacant architectonic structures that evoke solitude. Nomata likens his creative process to “daydreaming in an awakened state of reality,” completing paintings over extended periods, imbuing his landscapes with a lingering sense of déjà vu. His works echo a history of urban landscape painting, drawing inspiration from diverse sources such as Charles Sheeler, Lyonel Feininger, Op Art, Symbolism, and Art Deco.

Devoid of identifiable markers, Nomata’s silent landscapes traverse nuclear ruin, cosmic infinitude, industrial glare, and the ever-changing dance of solar energy. His paintings encapsulate the ambitions of human endeavor contending with the boundless mysteries of an unknowable universe, inviting viewers into a realm where past, present, and future coalesce in a symphony of enigmatic beauty.

An Interview with Minoru Nomata

By Carol Real

Can you elaborate on how your childhood surroundings near the Meguro River impacted your aesthetic vision?

I grew up in a town where I had no experience of nature. The Meguro River is now a popular place for cherry blossom picnics, but it was originally designed for drinking water and agricultural irrigation. In my childhood memory, it was a river with a revetment that discharged domestic and industrial wastewater and it was anything but far from beautiful. However, the surroundings shaped my values, which prefer taps to flowers, things to events, and phenomena to feelings.

In terms of aesthetics, I clearly remember the scenes of colorful kimonos and fabrics on many poles flapping in the wind on a sunny day, as my family ran a dye house. Patterns and colors of kimonos were always there in my house daily, and it was related to traditional Japanese paintings. I was not aware of it, and it was the non-Japanese culture that interested me at the time, but now I feel that it planted a foundation of aesthetics in my subconscious.

How has Tokyo, where you live and work, influenced your artistic journey?

Tokyo always surprises me with the speed with which the old buildings are replaced by the new ones. The speed of metabolism and the state of statelessness offers me inspiration for stateless structures. In this sense, urban areas are the places where we can simultaneously project the past, the present, and pioneering visions, providing a sign of the future direction of time.

The design of buildings and cities is not a direct source for my paintings, but it stimulates me enough to inspire creative motivations.

How has your background in design at the Tokyo University of Arts influenced your approach to painting?

My major was formative design, but it was the place where we learned all kinds of art and where we were allowed to create anything, rather than make a specific design. As a result of the school’s emphasis on history, I mainly learned about classical Japanese art and classical patterns from all over the world. Now I find that this exposure has subconsciously nurtured my interest in classical artistic expressions.

You held your debut exhibition at the Sagacho Exhibit Space. How did this alternative gallery define your early career?

It was 1985 when I first met Kazuko Koike, who was the founder and director of the Sagacho Exhibit Space. There were no alternative spaces like Sagacho Exhibit Space and almost no contemporary galleries in Tokyo. I didn’t even know what the word “installation” meant at that time. The alternative space taught me the relationship between the place and the artworks, the importance of installations, and how to erase the boundary between art and design. It had a significant impact on my career, not only in the early days but also today.

Your early works draw on Greek and Roman architecture and classical ruins. Can you explain how these influences have evolved in your art over the years?

While Japan has a wooden culture and suffered from natural disasters, much Greek and Roman architecture is made of stone. It was natural for me to be attracted to the temporal length of time that stone architecture has. Thinking back to my childhood, there was a stone chimney of a public bath, towering over 20 meters high next to my house. I always felt relieved that “my house is under that chimney” by finding the stone beacon from a distant point in the area.

However, as I think of the permanency of materials after making some series, the strength of the impressions or memories began to predominate over the physical strength. It was when I started to make the structures away from the physical volume of matter. This context is still a part of my architecture, and I’m no longer influenced by those stone traditions now.

The architectural elements in your artworks frequently exhibit a blend of familiarity and mystery. Could you provide more insight into the inspiration behind these particular forms?

I always have the following criteria: past (past events, things I liked in the past), present (things that are currently at the center of my consciousness), and future (something curious or troubling). I always try to record them as visual information by making a scrapbook. There are more than 50 scrapbooks that are the main sources of my inspiration. It is difficult to describe in detail what I collect, but there are, for example, images that have strong horizontal, vertical, and deep impressions, vast landscapes, high mountains, and towers. Lack, deficiency, insecurity, isolation, and the unknown–those so-called negative feelings can also be a creative trigger for me to create something.

The absence of human presence is a notable aspect of your paintings. Could you discuss the significance of this decision?

When I think about the significance of drawing humans, I think that the personality of the portrait is unnecessary or might even prevent viewers from imagining who they are. I thought that I should not be the one to decide the age, gender, body shape, clothing, or nationality of the people in the artwork. It is totally up to the viewers who will look into those artworks to place any humans or not to place humans.

I always wonder why people from all over the world have the same question, while there are many postcards of tourist places without people. I think it is quite natural for people to want to be in the front row to see something, whether it is sightseeing or when the curtain goes up on a stage.

You noted that your work is influenced by music, with a specific emphasis on the works of Brian Eno and Erik Satie. Could you elaborate on how you incorporate musical elements into your visual art?

I borrow the ability of certain pieces of music to amplify my imagination. It enables me to imagine something wider, deeper, and more lasting.

I also use guitars and sound equipment to compose the images through sounds. Music is an essential part of my production.

In your early work, the shift in scale and neutral palette recalls artists like René Magritte and Giorgio de Chirico. How have these artistic influences shaped your style?

The paintings of the past tell us how to capture depth, shifting colors, and shadows that are difficult to capture in real-time and space. I have learned from them how I can translate soothing images that make us want to breathe deeply into two-dimensional works. Perhaps I might have touched some kind of unknown memory that their artworks have.

You’ve mentioned that Charles Sheeler, the American precisionist painter, is an influence on your work. How does his machine-age aesthetic connect to your experience growing up in Tokyo?

I was born in 1955, in an industrial area with many small factories. It was a time when various construction projects for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics were taking place all over the cities, starting with the construction of the highway. I studied design at university fascinated by the poster of the Tokyo Olympics which was designed by Yusaku Kamekura, but I had a notion that art and industry were something like water and oil that could never be mixed.

When I saw Sheeler’s paintings for the first time with his art book, I was impressed to know that something industrial, the world that I saw every day, could be an artistic setting that was positively accepted as art. The art that I knew at that time was always related to nature, and I had no idea that industrial landscapes which are made of mass consumption could reach the domain of fine art. Charles Sheeler gave me the idea of the fusion of industrial themes and fine art.

The inception of your paintings frequently involves images sourced from magazines and newspapers. How do these visuals transform into your distinct visual language?

My creation begins by paying attention to daily events including world news and academic TV programs that focus on history, mathematics, astrophysics, and so on. At the same time, I keep visual information from magazines or newspapers in my scrapbooks, then I make sketches by referring to this information and visual images. Various events in society and fragments of images and graphics are accumulated, they emerge as images to be painted on the canvas or watercolor drawings on paper at some point. I do not know which sketches will grow into paintings or drawings. Sometimes it takes several years to sort them out in my mind and be ready for output.

I always try to make something that has polysemic meanings, not having a single meaning or message, and this variety of visual information allows me to realize it. I believe that ambiguity stimulates people’s imagination and provides room for interpretation from multiple viewpoints.

The recurring theme of construction and ruin in your work is noteworthy. What do these themes represent to you personally?

Many people associate my paintings with ruins, but I had never thought of drawing ruins or using the word in my creations. I draw each object while retaining the sense of construction. However, I can say that it might be quite reasonable for viewers to experience the feeling of devastation because I always think of a world in which construction, restoration, and demolition are happening simultaneously.

Here I have to say that I would never willingly explain what it means or what they are. I have avoided answering such questions as much as possible, so as not to prevent people from expanding their imaginations, by giving “’the right answer.” The essence of my artwork is “a question,” and that is exactly what I am asking the audience. It is all about what the viewer perceives, rather than the message the artist conveys.

Wind turbines and greenhouses appear in your art from the 1990s. What is the significance of these elements?

The passage of time brings some change in awareness of problems or interests. My mental state, awareness of problems, and interests generate some kind of form of modeling. I was trying to find a place with a good wind–that was my mental state at the time after overcoming family illness. However, most states of mind cannot be explained and that is why I translate them into visual art.

The “Bourou” or watchtower paintings from the 1990s have a unique, glowing quality. Can you explain the inspiration behind these works?

It was a reflection of my mental condition. I drew mountains more than ever in the “Bourou” series, because my daughter fell seriously ill. It took all my strength away from me and I had no will to resist anything anymore. All I could do was hold on to nature, such as trees, rocks, and mountains.

The “Windscape/Perspective: series explores atmosphere and movement. How do these works relate to your overall artistic vision?

Each piece of my work is correlated and it is quite difficult to cut out the particular series’ relation or effect of each series to another in most cases, as the survey exhibition at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery was titled Continuum.

© the artist. Courtesy White Cube

Your more recent paintings seem to focus on fragility and human vulnerability. What messages are you trying to convey through these works?

I am a painter and what you see on the canvas or paper are my words to output my messages, so I do not have specific words to clarify my message. I do not want the artworks to have clear answers or limitations that prevent people from imagining the possibilities, as I mentioned above. Removing literal or specific meanings is one of the important creative processes.

One thing I always say is that I am trying to depict the things that are not directly expressed on the canvas. That could be the time, layers of the ages, traces of the humans, a background, or sometimes it might be a premonition that something would happen.

Climate change is a global concern, and you incorporate windmills and solar discs into your works. How do these symbols reflect your views on the issue?

I have been drawing wind turbines and solar discs since the 1990s, but now we are living in a world where we cannot even maintain the status quo. I am disappointed that the global environmental efforts have not progressed, as everyone feels.

Your Light Structures and Skyglow paintings address the abundance of electric light in urban areas. Can you explain the social and ecological themes in these works?

I am trying to avoid explaining the theme itself, and clarifying the meaning of my art, but I can talk about the background of the theme. It was before the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima that I created the series focusing on light. I had a kind of discomfort with the amount of energy that has no limit, seeing the thousands and millions of lights in the city area. I intuitively imagined that some kind of balance would eventually collapse if we tried to sustain this lifestyle.

However, it was also true that I was in an ambivalent situation. I found artificial things like quarries beautiful, despite the sense of crisis and guilt. The situation continues even after the problem has become more apparent, and I am disappointed in myself for still using enormous amounts of energy in my daily life.

The Tower of Babel is a recurring theme in your art. What does this symbolize in the context of your paintings?

I was not aware that I had drawn the Tower of Babel so many times. I drew it not because of its importance but because it is necessary for me. It has been quite a while since I last drew the Tower of Babel, but I remember that I started by thinking about nations, centralization of power, class, and the capacity of the world.

Can you discuss the balance between optimism and caution in your portrayal of modern urban environments?

It involves addition, subtraction, and synthesis. It also depends on how I feel at the time. It might be similar to the feeling when we choose the side dishes to make a good lunch plate with a good balance.

Your exhibitions have taken place in various locations, including the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery and De La Warr Pavilion. How does each venue impact the presentation of your art?

I value the land as well as the space. I understand that the place becomes part of the installation, and the installation is part of the artwork. I think of my installations according to my intuition and I cannot explain how it affects them, but it does indeed affect a lot.

For example, the 2022 solo exhibition Windscape was held in a historic building which is located in the coastal area of East Sussex. I intended to make an installation that was reminiscent of the design of a ship’s mast.

As a professor at the Joshibi University of Art and Design, how did teaching influence your artistic practice?

Teaching is a different experience to being an artist when I confine myself in the studio all alone. It stimulated me a lot, but my hands were full of lectures, staff meetings, and a four-hour round-trip commute. I have to say that my creative time halved during this period.

Can you share a pivotal moment or experience that significantly impacted your work?

My family’s health conditions, Japan’s bubble economy in the late 80s and early 90s, the September 11 attacks, the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. My work is influenced by my personal situation as well as global events that mark the turning point in each era.

The images of the Tohoku tsunami engulfing the coastal area shattered my belief in the protective power of architecture. They also drowned out the architecture in my imagination and it took me several years to draw a stable structure again.

How do you manage to evoke a timeless essence in your paintings, and what significance does this hold for you?

I think the sense of timelessness comes from my experience of reading several science fiction novels in my late teens. Philip K. Dick’s work in particular encouraged me to think that adults can also be allowed to conceive of things in the same way as we did in our childhood.

The experience of encountering Brian Eno’s music was also a great influence on my thinking about timeless expressions. I remember being greatly inspired by the statelessness of Eno’s music and the indication of an unknown place or time when I was trying to make a work of art with a chimney in my days as an office worker. His music was something that I could not categorize in any music genres I knew, and I became skeptical of the categories that already existed. He instilled in me the value of thinking without boundaries and emphasized the importance of not constraining my expressions within conventional wisdom.

In what way does your art balance the known and the unknown?

It depends on the particular situation, and where I am in the process. Nothing is standardized and all I can do is try and error.

The relationship between nature and man-made structures is a recurring theme. How do you view this relationship in your paintings?

I imagine that my desire to be close to nature draws nature into artificial structures. I feel like I am making up for something absent. I am not sure of my analysis, but one thing is for sure: nature is what I do not have in my life in the urban area, from my childhood up to the present day.

Can you discuss the role of imagination in your creative process and how it guides your art’s narrative?

Imagination forms a chain of creation. One artwork brings a different story, then a new narrative follows one after another. When one series of work is completed, I have already found many of the points where there is room for improvement. This introspection also becomes the driving force for the next series.

In your opinion, what is the primary purpose of your art, and what do you hope viewers take away from it?

Drawing is my routine and I do not have a particular purpose for drawing something. Each drawing is a result of the projection of my feelings. The thing is that I keep on drawing. It might look like I have a great discipline for that because I have been doing it for nearly four decades.

It is up to the viewers how to perceive my paintings, and I hope they have open interpretations. I intentionally attempt to offer multiple meanings and avoid a single feeling or viewpoint. I am sure that they will be viewed differently by different people, from different countries or with different backgrounds. I am open to my artwork being interpreted in any way, as long as I can keep on drawing as a painter. I might say “It’s a bit different” quietly within my mind if I found any discrepancy in the interpretation, but just that.

What future projects or themes are you excited to explore in your upcoming work?

My artworks are a reaction to something. The change in the environment or the world situation makes different pieces of art, and I am afraid to say that I am not the one who holds the handle to decide the direction. They are natural results of my natural reactions. However, I always want to have a blank page in my mind, in the sense of being ready to accept new scenery in the future.

All images courtesy of Minoru Nomata and White Cube Gallery.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista