Artist’s Biography

Luis Felipe Noé was born in Buenos Aires in 1933. He initially studied at Horacio Butler’s workshop and later continued his artistic training as a self-taught artist. From 1956 to 1961, he worked as a journalist for the newspaper El Mundo, where he wrote art reviews. He has lived in both Paris and New York.

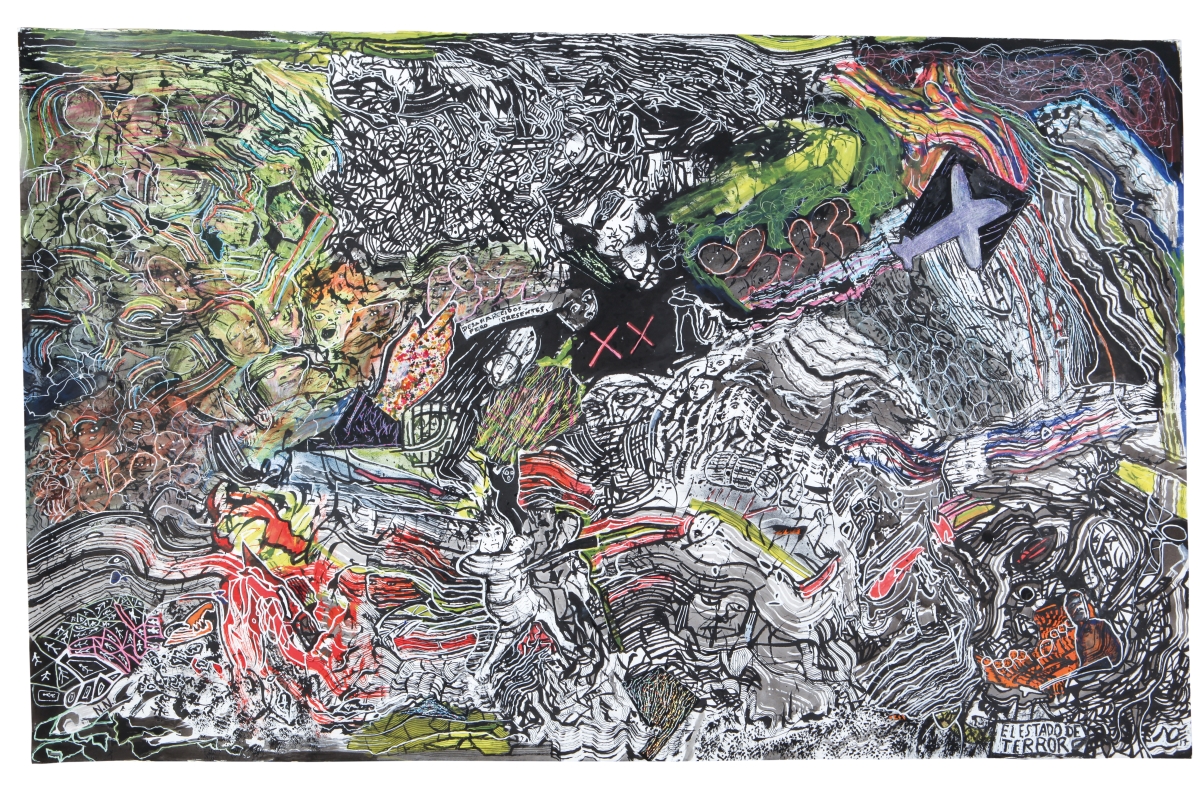

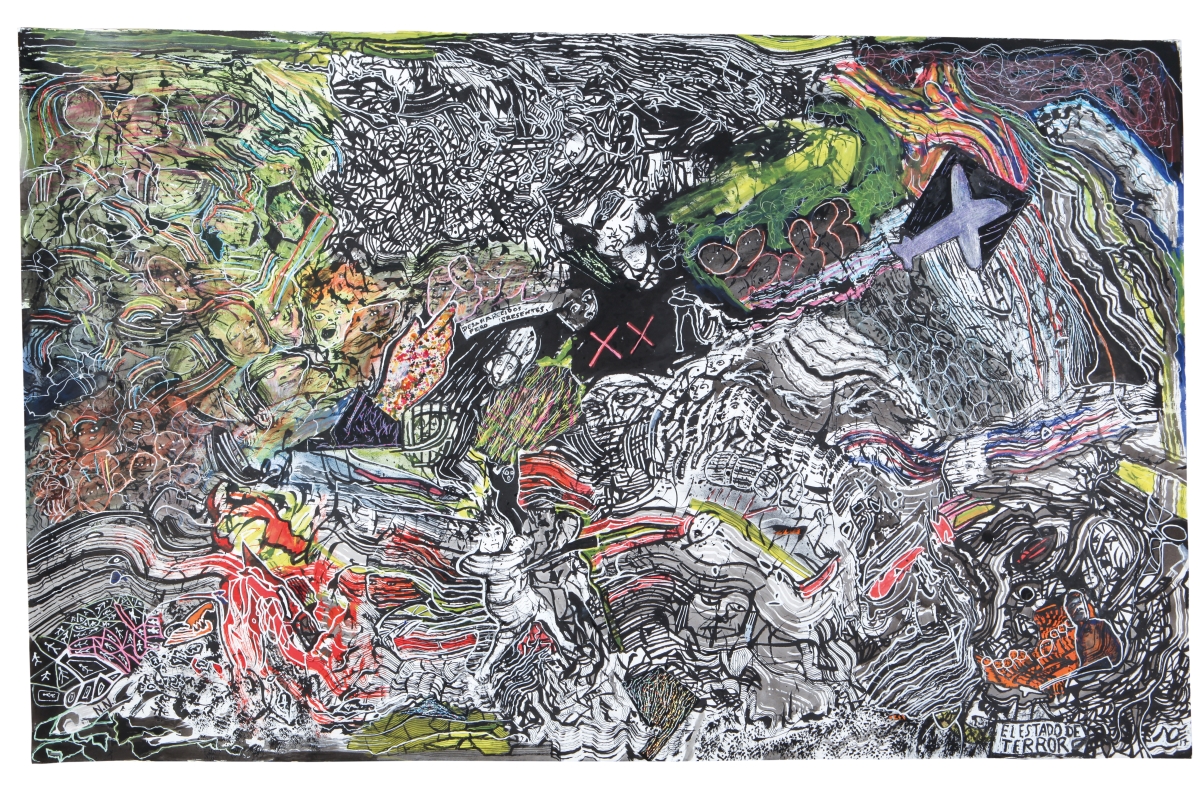

Between 1961 and 1965, Noé was a member of the group known as New Argentine Figurative Art or Other Figurativism, alongside Ernesto Deira, Rómulo Macció, and Jorge de la Vega. The group was invited to participate in the Guggenheim International Prize in 1964 and received honors in the historical section of the São Paulo Biennial in 1985, at the Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires in 1991, and at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in 2010 with the retrospective exhibition “El estallido de la pintura” (“The Burst of Painting”).

Since 1959, he has held over one hundred solo exhibitions. Notable retrospective exhibitions of his work have been held at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires (1995), the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (1996), and the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (2010). In 2009, he represented Argentina at the 53rd International Art Exhibition in Venice and was a guest of honor at the XX International Biennial of Curitiba in 2013. In 2017, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes dedicated an exhibition called “Noé: Mirada prospectiva” to him, which showcased his practice of chaos theory.

Noé has published numerous books, including “Antiestética” (Van Riel, 1965; De la Flor, 1988, 2015), “Una sociedad colonial avanzada” (De la Flor, 1971), “Códice rompecabezas con recontrapoder sobre cajón desastre” (De la Flor, 1974; Fundación Luis Felipe Noé, 2021), “A Oriente por Occidente” (Dos Gráfico, Bogotá, 1992), “El arte en cuestión” (Adriana Hidalgo, 2000) with Horacio Zabala, “Las aventuras de recontrapoder” (De la Flor, 2003) with Nahuel Rando, “Wittgenstein ese es el caso” (Ediciones Malvario and Albatros, 2005), “Noescritos, sobre eso que se llama arte” (Adriana Hidalgo, 2008), “En el nombre de Noé” (Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, 2009) with Noé Jitrik, “Mi viaje – Cuaderno de bitácora” (El Ateneo, 2015), “El caos que constituimos” (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2017), “En terapia” (Galería Rubbers, 2018), and “El arte entre la tecnología y la rebelión” (Argonauta, 2020).

Throughout his career, Noé has received several awards and honors, including the Premio Nacional Di Tella (1963), grants from the French government (1961) and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (1965 and 1966). He has been awarded the Gran Premio de Honor del Fondo Nacional de las Artes (1997) and the Konex Brillante a las Artes Visuales

Bio source: https://www.luisfelipenoe.com/

Social media

instagram:@yuyonoe

facebook @noeyuyonoe

Interview

By Carol Real

How has the concept of the avant-garde evolved from its origin to the present day, and what is the current state of creativity and innovation in contemporary art?

The avant-garde is a very particular phenomenon that emerged at the beginning of the last century, after the crisis of the 1930s. At the end of World War II, the United States felt the need to culturally promote its image against the Soviet Union and proposed New York as its great flagship.

However, after that moment, the promotion of artists became an individual pursuit. Artists went their own way. Then, Pop Art was promoted as a distinctive representation of the current society. Subsequently, Minimalism arrived, which marked the end of the avant-garde.

Since then, the avant-garde has become individualistic, and what I call the “art cocktail” emerged worldwide. “Art cocktail” consists of everyone drawing upon all the past movements, including those predating the emergence of the avant-garde by several centuries, as well as the past avant-garde movements, each artist following their own path.

Currently, some artists have a truly avant-garde spirit, proposing new things, while others adopt a more reactionary attitude or lack creativity. I believe this is somewhat happening today.

In addition to being a teacher, painter, and writer, you have been an art critic for many years. What does an artist need to achieve excellence? And what characteristics should an avant-garde artist have?

The concept is simple but at the same time broad. What I want to express is that an artist must have a creative proposal that arises from the artist’s own spirit. What do I mean by this? Artists must go beyond themselves, understand and absorb the world around them, be moved by it, and structure a proposal in the face of the constant change that surrounds us. When I mention chaos, I’m not referring to disorder but to the permanent transformation that occurs in time and in general.

You mention that chaos is a kind of eternity and that time is part of that chaotic scenario. How do you perceive the relationship between chaos and time?

I just finished writing a book called Assumption: Embracing Chaos. I am about to publish it, and it is over 700 pages.

When faced with the chaos that surrounds us, one of the ways to be oneself—because I believe we all integrate chaos—is through the possibilities of artistic development. I’m not saying it’s the only way, but it is the most prominent in a certain sense. In that regard, I think materializing our work with a certain proposal is a way of facing and embracing the chaos that surrounds us. It is a proposal to the society we inhabit.

Yes, how do you see chaos? It’s not like before. In the early avant-garde of the last century, the avant-garde was a rupture of prejudices. Now, all prejudices are broken. Avant-garde at this moment is something else. It is being able to propose, to be the owner of your freedom, right?

How does chaos relate to freedom and determinism? Can we genuinely consider ourselves free in a chaotic world?

Freedom consists of embracing oneself amid general confusion and being able to structure oneself. I don’t think chaos should be associated with disorder because order and disorder are static elements. In contrast, chaos is like time, it is experiential within the concept of time. It is in constant flux; the very concept of order is just a footnote within the general chaos. Even in moments of apparent tranquility and order in society, new changes and things are forming. We may not perceive it overtly, but then we realize that it has been latent, and everything has changed. At 90 years old, I have perceived radical changes in customs and human society that are much more significant. I am referring to small cultural revolutions like feminism and all behaviors related to gender and the ability to choose one’s gender—things that were unthinkable when I was young.

Changing the structure of language to understand that the word “man” is now something else; when we say “man,” we are referring to humanity. Now, that word cannot be used in the same way. The word “man” has become obsolete. It is simply a gender.

These changes are closely linked to technological advancements, especially in recent years. Fifty years ago, you wrote a book that took you three years to complete and another 50 years to be published. What was the public’s response to the work titled, Art Between Technology and Rebellion?

For me, having published it 50 years after its creation, it still addressed very current topics. I didn’t publish it when I conceived it in the United States because of what was happening in the 1960s. Between my book and the works of Marshall McLuhan and Herbert Marcuse, there were very different paths, but a shared appreciation for how technology was changing.

The concept of the aesthetic generation in art itself. When I came to Argentina that was what predominated. Although it may seem unbelievable, that was very confrontational because it led to political action, and at that time, the situation here was very harsh. So, I thought it was wiser not to publish it. When I finally did publish it, I felt that the situation had changed somewhat. Some people encouraged me to do it, but it’s evident that it was a book for that moment, not for the present, due to the significant changes that have occurred.

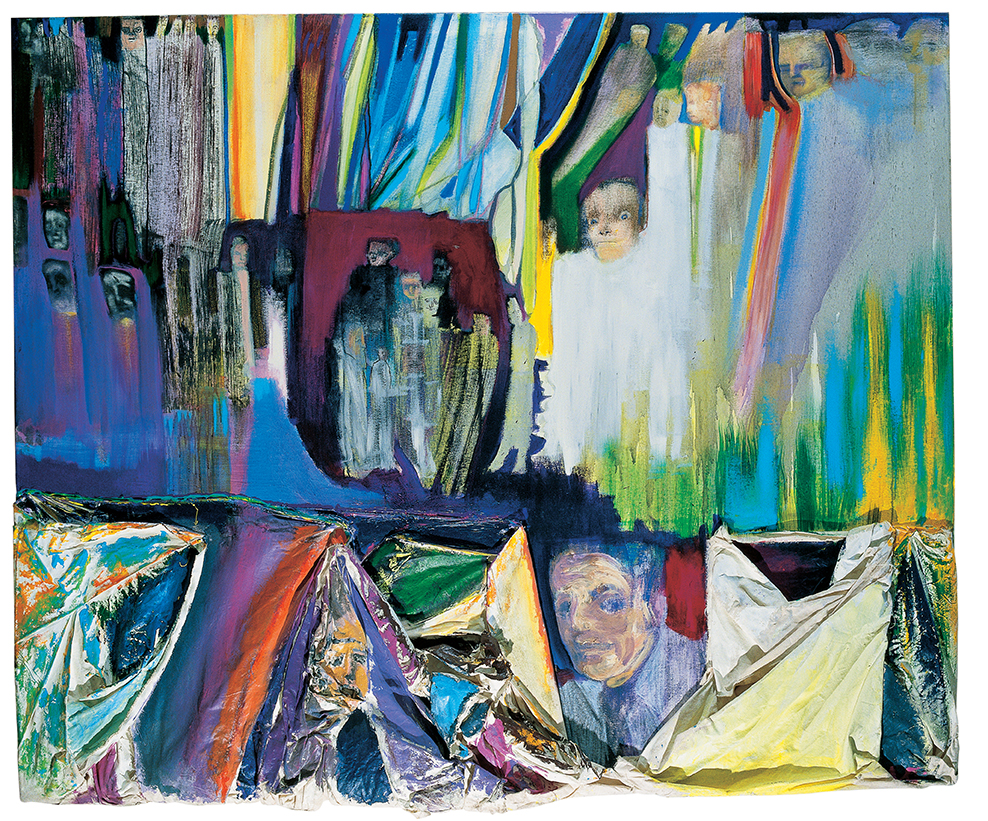

You are 90 years old, and I can imagine that your approach to work has evolved since your beginnings. You studied with Horacio Butler for a brief period of a year and a half, but then you chose self-teaching, exploring different artistic techniques and styles. Throughout your career, you have experimented with both acrylics and oils, although I understand you temporarily abandoned the use of the latter medium.

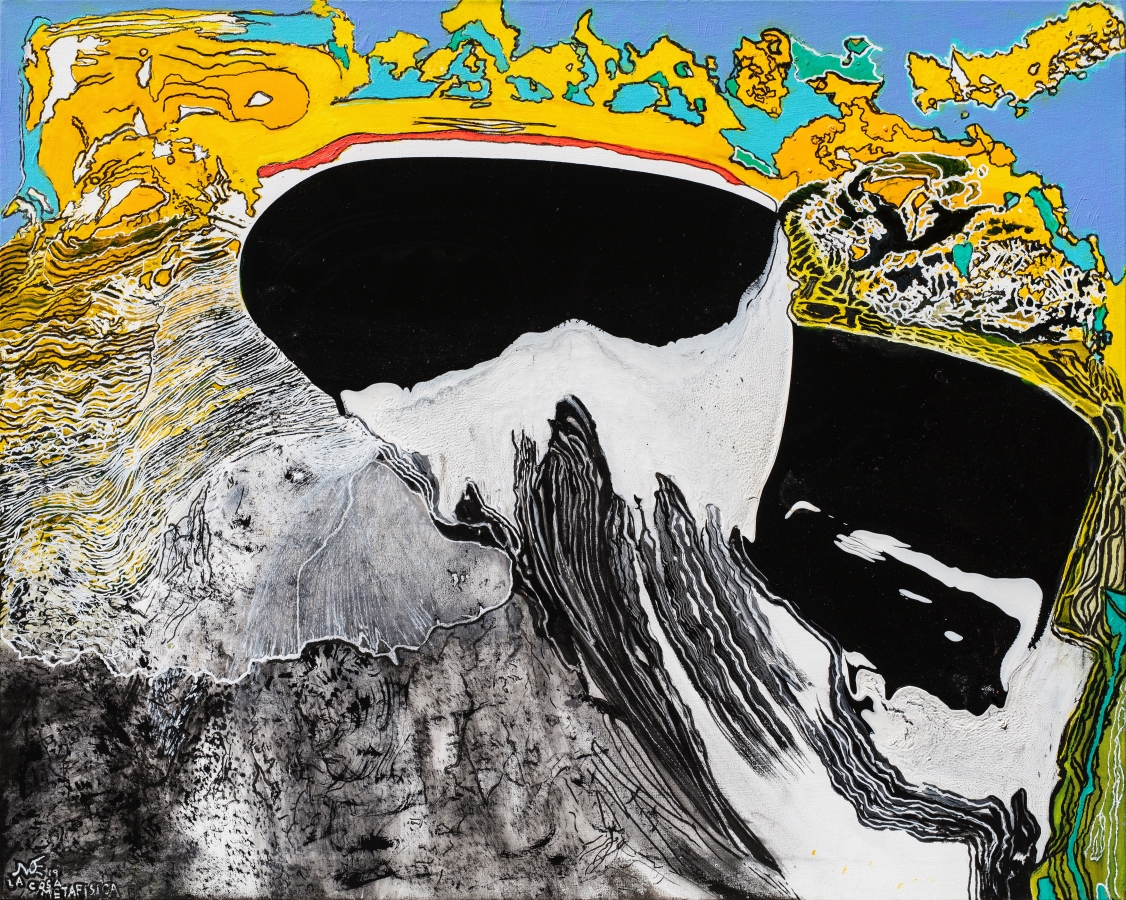

What happened is that when I started painting acrylic didn’t exist. I used enamel paint, the same one used to paint walls or furniture. I also used different Indian inks. Now, I especially use Indian ink and acrylic. That’s what I currently use, although sometimes I feel nostalgic for working with oil. They are different ways of approaching color and material. And there’s something I don’t like: repeating myself.

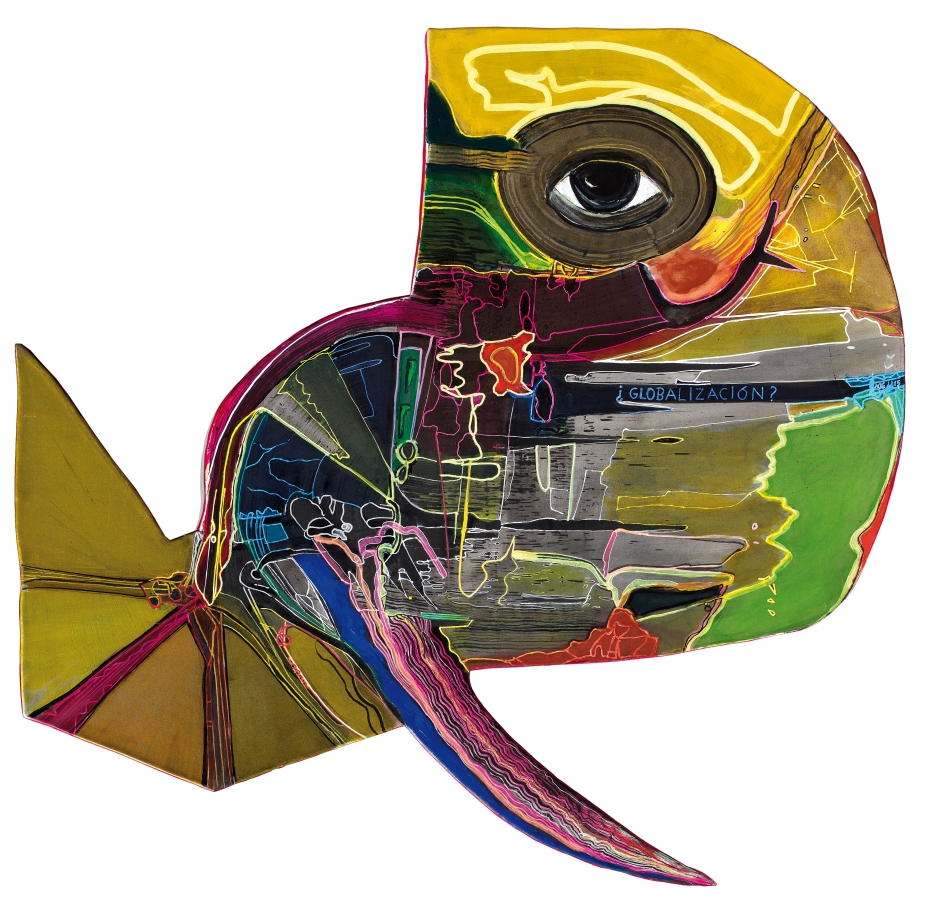

I have one notion, which is to overcome the difference between figuration and abstraction. It seems ridiculous, right? Yet, I pursue it in different ways, sometimes being more figurative, other times more abstract. At the moment, I’m more inclined towards the abstract. However, in language itself, when we speak, we use more words with abstract content than figurative. For example, when we say, “This table is beautiful,” we are already in the realm of abstraction. It may be beautiful to some, but not to others. And what does beautiful mean?

People argue and are capable of defining very different ideologies; even going to war. And generally, this happens because of abstract matters and concepts. This is not something figurative; it is the abstract that dominates us. Philosophy would not exist if it weren’t so.

I think that is the great difference between scientific thinking, which is concrete and figurative, and philosophical thinking, which is fundamentally abstract.

When discussing your self-portraits, you mention that you merge landscape with abstraction. What does that mean to you, and how is it reflected in your art?

In a way, every work by an artist is a self-portrait. Now there are two ways of experiencing painting; many say that painting is already finished and such, and I fully believe in that because it is a fundamental way of projecting the individual spirit, right? Some things cannot die.

Painting cannot die. It’s fashionable to say that painting is dead and to conceive of art in ways other than painting. But why don’t they say that music is dead? Why don’t they say that literature is dead? They focus solely on painting. They are not right, to tell the truth; there is no valid argument. It’s just snobbery, among other things. For me, painting is my language, it’s my way of being, and I conceive it in the same way that music is conceived. The elements to compose something musically have their equivalents in painting. Some believe that after photography, painting has lost its meaning.

However, painting is beyond that. It’s like music— an inherently abstract combination. The spirit of painting is abstract, even when it appears very figurative. For example, when we talk about chiaroscuro in classical painting or in works by great masters like Rembrandt, what is it if not abstraction?

Additionally, I like the material that you have used in many of your works: mirrors. Do you still work with them?

This idea of mirrors also arose in the United States when I saw a business selling bendable plastic mirrors. I created an installation with mirrors where everything was reflected and visually changed as a distortion. It was a long process and remained incomplete, although I did something similar in Venezuela in May 1968.

During an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Caracas, the material they provided me was not reflective enough and of poor quality. It was an experience. Sometimes I have worked with this material, but it remains unresolved. Many of my explorations have ended with ellipses. I feel that my life is an ellipsis, and one fills in those dots as one lives. Yet, when a situation has passed, the past also remains with ellipses.

What are your thoughts regarding technology and how it affects the presentation and execution of artworks? Nowadays, it’s possible to create a painting simply by pressing a button. Many people consider it a work of art, while others argue that it is not the result of a genuine artistic process. Is a machine creating artwork? How can we truly define a work of art in itself?

It has to do with an evaluation of what technology, at one point, seemed to propose more changes. Now, there’s talk about the possibility of creating a man, a human being, in the same way that animals are created, although ethically it is discouraged. I believe that currently, there is a fear that technology may surpass true creative human thought. However, I think that there will always be a human behind all of that, the man who challenges himself. In a way, it is man who ultimately accomplishes all of this, creating his own enemy if you will. But above all, I believe in the human spirit.

Also, the Internet has allowed real-time dissemination of artworks, such as paintings, sculptures, and other media. Today, it is possible to exhibit or sell these works without the need for a physical place like a museum or a major gallery. This tangible presentation has now taken a back seat, and museums are no longer considered the main institutions people want to visit.

What happens is that nowadays, the economic evaluation is mixed with all of this. So, the market is different now, but when I talk about art, I forget about that, right? I mean, some people revolve around art, but they’re not thinking about the creative aspect—rather, the social phenomenon of art. They give value to the market, to all of this. For me, it is just an anecdote. The only thing that exists as artistic matter is the artistic matter.

What I mean by that is the human spirit projecting itself onto the work. That’s it. Everything else is noise. It’s surrounding noise.

What keeps you active and occupied with projects, painting, and writing at present? What keeps you so alive, so young at 90 years old?

I don’t know; I don’t get bored. The only thing I can boast about is that I don’t know what boredom is. I can be alone, alone, alone and I make jokes to myself. I constantly talk to myself. I feel like I’m populated by a world that is the projection of everyone and it’s within me. I think it’s because I’m a Gemini. And with all the signs of Gemini, I feel, not two, but already a collective full of people. This is a very Argentine collective, a bus full of people… the problem is who’s driving it. Sometimes, I’m a person driving my own bus. Other times it’s someone else driving my own bus or a person within myself. I can be several people at the same time, but that’s not very original.

I read that Rilke thought the same. At some point, the most creative thing one can be is the enunciation of something new, of oneself.

You have lived in New York and Paris, you have traveled, and have the doors of the whole world open to you. Your works and your career are phenomenal. What made you decide to return to live in Argentina?

It’s because I’m deeply from here. In New York in the early 60s, I fell in love with everything that was happening. But I think present-day New York is very different from that time. Anyway, I can’t talk much about New York now because I haven’t visited in many years. It’s the impression I have from afar. And France? What attracts me the most about France is that my children are there, and there are also people whom I love very much. Every time I go to France, I’m interested in seeing them.

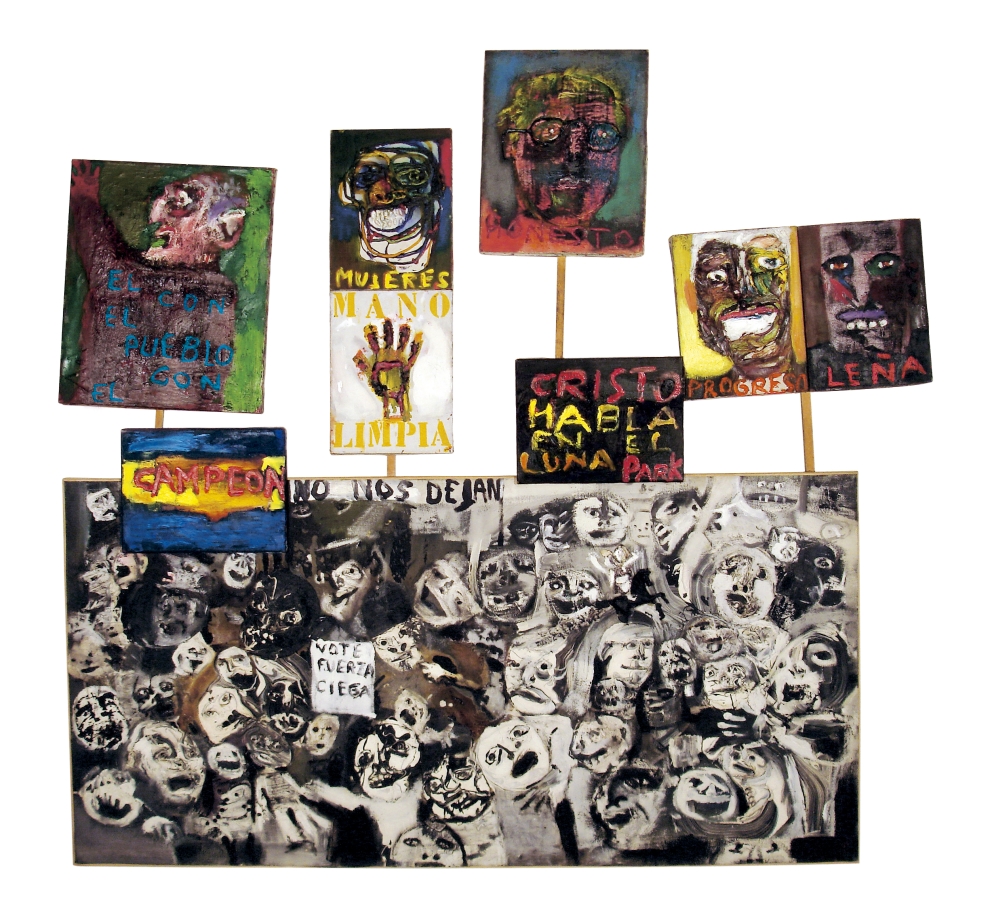

Yet, in itself, France is good as a cultural entity. There are books because I think that culturally the most alive thing in France is all its thinkers. That’s it. Even so, I always think that it’s better to read the French intellectual than to know them personally. Well, here I feel in my place, I don’t know, but I simply feel it. I feel Argentina with all its disorder, with all its things, but it’s the place because it invites me to think about chaos, in a way. Still, I don’t think it’s exclusive to my country. I think it’s something from the whole world, but here it’s clearer. We don’t claim, although some people claim that we are what we are not. I believe that, in general, here we have to accept that as a society we are not yet fully formed. And that’s interesting.

Now, if I define myself at the level of consciousness, above all, I feel Latin American because I think all of Latin America must define itself, and in that sense, there are many different forms. Each country contributes with its own identity. Precisely because of those different ways of being, a very particular vitality is defined. And that’s what interests me. I think it’s crucial for the concept of empowerment and for being able to exist in the world. Why? Because the truth is that both in Europe and in the United States, there is a certain disdain towards Latin America, but I think that if we affirm our power, that disdain can be reversed.

You have forged friendships throughout your career with artists like Ernesto Deira, Rómulo Macció, Jorge de la Vega, and Greco. Most of them have been painters. Is there any anecdote you can share about them? Something you remember at this moment in your artistic career?

León Ferrari, was a very good friend of mine and same with Ricardo Carpani. Yes, I have had great and important friends in the art world, including some with whom I have shared significant phases, such as Luis Camnitzer and Liliana Porter, who live in the United States.

At my age, I no longer need as much support from another person to be myself. Yet, a friend who was very significant to me was Jorge de la Vega. I can also say that Alberto Greco was important, although our friendship was short-lived due to his suicide and the difficulty of maintaining a good relationship with him. He was complicated.

I can share an important anecdote. I would say it was my first day—essential in my entire artistic experience. I can give an exact date: October 5, 1959. That day, I opened my first exhibition, and Horacio Butler, who was my professor and had received post-cubist training from Andrés Lotes and others, was present. He had a very structured teaching method, and I think I questioned it a bit. At one point, he said to me, “After a year and a half, I have nothing more to teach you, right?” This was a way of indicating to me where the door was, right? We maintained a distant relationship, and I would visit him sometimes, but I dared to continue on my own and, above all, to learn independently. However, he gave me an important push, but not by following the orthodoxy of his thinking. It was then that I opened my exhibition, and he was waiting for me at the door. He said, “I was waiting to tell you that by doing exactly the opposite of what I taught you, you have achieved a good result.” That also demonstrates the kind of person he was because it’s not easy to say something like that.

That day, I entered the exhibition, and there I met people whom I barely knew, who were not yet my friends, like La Vega, Greco, and Macció.

Later, my father told me that he was liquidating the hat factory that had belonged to my grandfather, and he offered me the place to paint. I took the opportunity, and soon they were there too. That’s when my artistic journey began.

During your artistic journey, you must have faced numerous ups and downs and obstacles. How have you managed to overcome them throughout your career?

When I wrote the book Art Between Technology and Rebellion, I suspended my artistic work for nine years. I didn’t paint, but at that time, I experienced a personal crisis and started therapy. I did it for a year and a half or more, and while I talked, I drew. That’s when drawing came back to me, and after those nine years, I resumed painting. However, I think my crisis began with the interest in overcoming the idea of painting as something flat. I have always been interested in installations as a way of addressing all the contradictions around us. I accepted an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts that reflected the root of my crisis, stating that we live in a time when art cannot represent symbols. Although at this point, I’m not as interested in symbols anymore because there is a certain relationship. I don’t worry as much.

I mean, before, when one is young, there are moments of searching for oneself in the world. However, I no longer search for myself in front of the world; I simply am. By saying “I am,” I am around that. Perhaps that’s what I can say at 90 years old. The world finds you.

* All images are copyright courtesy of the artist.

Fundación Luis Felipe Noé

Editor: Kristen Evangelista