Since the 1980s, Kiki Smith has captivated audiences with her multidisciplinary exploration of embodiment and the natural world. Born in 1954 in Nuremberg, Germany, to acclaimed sculptor Tony Smith and opera singer Jane Lawrence, Smith’s artistic journey began amidst diverse influences, eventually leading her to New York City, where she would forge her distinctive path.

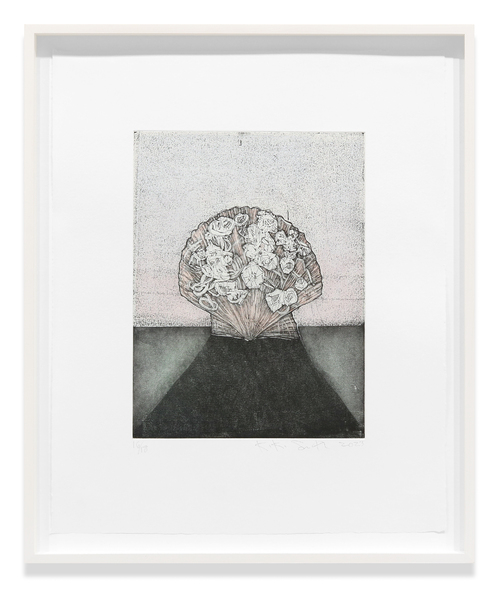

Smith’s oeuvre spans sculpture, printmaking, photography, drawing, and textiles, employing a diverse array of materials to continuously expand and evolve her artistic expression. Her early works in the 1980s delved deeply into the human body, often focusing on specific organs and bodily fluids, reflecting both personal experiences and the societal context of the AIDS crisis.

In poignant pieces like “Hand in Jar” (1983) and “Game Time” (1986), Smith’s exploration of mortality and corporeality confronted viewers with stark realism, provoking contemplation on the fragility and complexity of existence. Her relentless investigation into the human form extended to themes of reproduction and birth, addressing social and political ideologies surrounding women’s bodies.

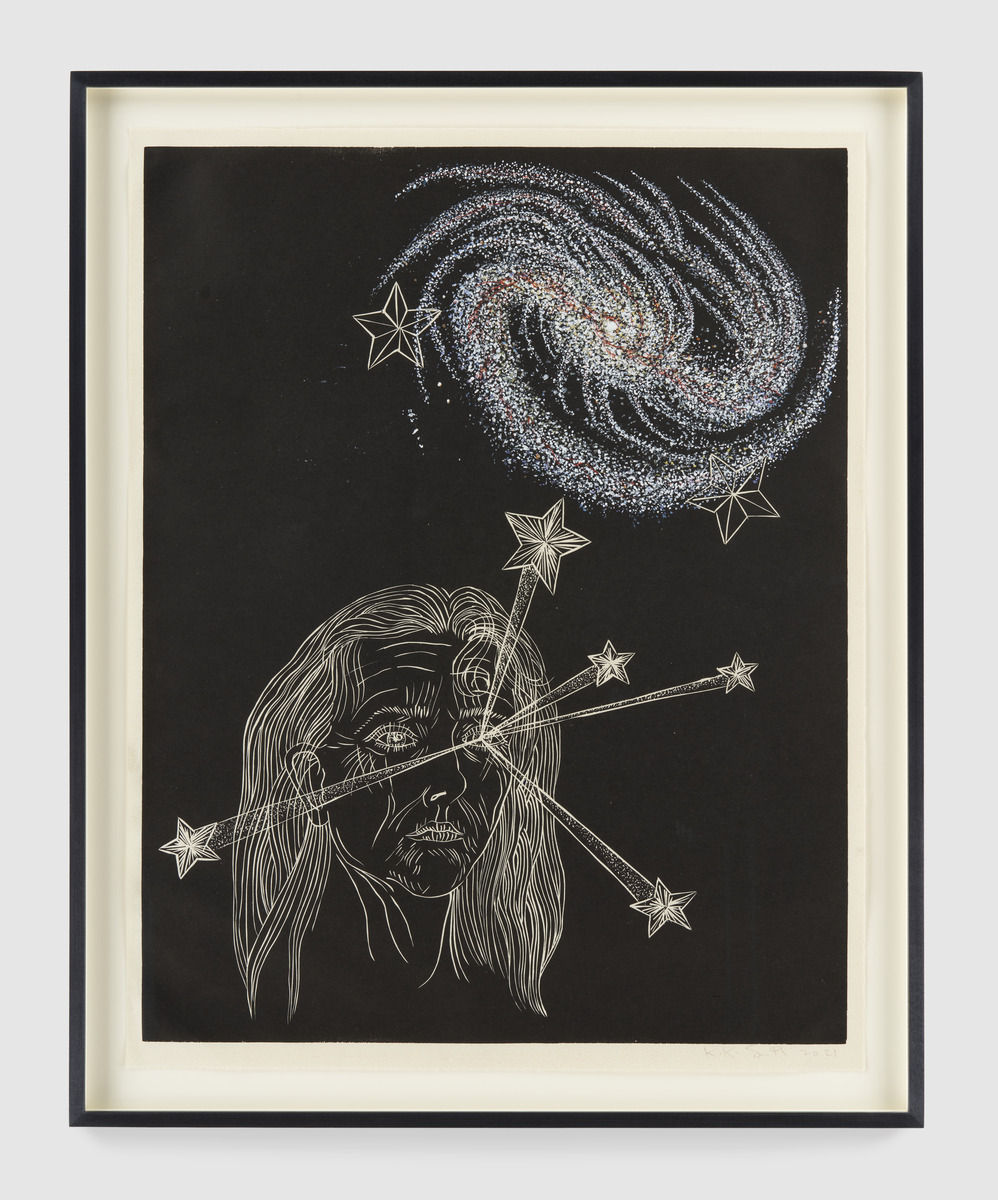

As the years progressed, Smith’s artistic repertoire expanded to encompass animal imagery, folklore, and mythologies, intertwining human and natural elements to create new narratives. From the hauntingly visceral “Untitled” (1990) to the mesmerizing “Sky” (2011), her work navigates the intersections of femininity, nature, and creation, inviting audiences to reconsider their place in the world.

Smith’s contributions to contemporary art have earned her widespread recognition, with over 170 solo exhibitions worldwide and notable accolades such as the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture (2000) and the U.S. State Department Medal of Arts (2012). She has been featured prominently in prestigious events like the Venice Biennale and honored by institutions including the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Beyond her artistic endeavors, Smith shares her wealth of knowledge as an adjunct professor at NYU and Columbia University, shaping the next generation of creative minds. Her legacy as a “thing-maker” continues to inspire, resonating with audiences through its raw honesty, profound beauty, and unwavering exploration of what it means to be human in a world shaped by nature and mortality.

An Interview with Kiki Smith

By Carol Real

Receiving the U.S. Department of State Medal of Arts in 2013 from Hillary Clinton is a unique honor. How do you view the intersection of art and diplomacy, and what role do artists play in fostering cultural exchange and understanding?

I and many other artists identify as part of their home communities and a greater international community of artists, where there are often creative exchanges. There is nothing more gratifying that I can imagine than sharing my work with people living in places other than my home.

As a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, how has being part of these prestigious institutions influenced your artistic perspective and practice?

I love being a member of the Academy of Arts and Letters and the Academy of Arts and Science. I love it when institutions directly support artists’ work and cultural engagement. I am delighted to have the opportunity to put forth other artists and writers and to become acquainted with the work I don’t know.

Your use of printmaking techniques is distinctive. How does printmaking contribute to exploring repetition and variation in your art?

A great deal of my work is generated through printmaking. I often start with a drawing that I transfer to a print medium and make large 2-D and 3-D pieces in collage, casting, weaving, or other techniques. I am most interested in seeing how an image migrates from one physical manifestation to the next and how changes in material and scale can give an image new life.

The fragility of life is a recurring theme in your work. How do you view art as a means to preserve and celebrate the ephemeral?

We can only temporarily preserve anything. Everything is ephemeral. Perhaps some entities reside as ghosts in the world or our culture that we are no longer directly aware of. I don’t know if anything is ever lost but it often can no longer be found. As an artist, I see my activity as being in the process. The process is my life, and the things I make are much more transient. They come and go.

Nature often plays a role in your work, such as in “Rivers and Tides.” How does the natural world influence your artistic vision?

The natural world is primarily what we have any contact with. Even all our immaterial thoughts may not be produced by us but are recognized by us. The natural world is what we are.

As an adjunct professor at NYU and Columbia University, how does teaching contribute to your artistic growth, and what messages do you hope to impart to your students?

I very much appreciate having been able to teach. I always get to learn from the next generation. I also am always learning new techniques and processes so that what I’m teaching is deeply invested in printmaking. We often invite other artists to join our class so that students can see how passionate artists are and have an experience outside of being graded on their work or fulfilling assignments.

Works like “Star” and “Meteor” reveal an interest in the cosmos and celestial bodies. How does the universe inspire your art?

We are the universe, we are in the universe. I look up to the skies every day and night. Our home is a vast skyscape to explore.

You often engage with the theme of transformation in your sculpture. How do you see the process of artistic creation as a form of personal transformation?

I find usually–maybe not while I’m making but after the fact–that what I’m making addresses myself personally. It reveals to me things that I need to consider. It makes my life more integrated and better. I deny any ambitions of following any particular path or getting anywhere. However, following my work and its transitory life leads me right where I need to be.

The repetition of forms in your work is captivating. How does this repetition relate to the concept of memory and its role in shaping our identities?

For the moments that I was in college, I studied filmmaking. I was very attracted to building a narrative through sequential images. I was interested in pixelation, which creates a ruptured continuity. This felt like a fractured fairy tale and much closer to me. In addition, I was highly influenced by my father Tony Smith who made much of his work by reconfiguring and combining octahedrons and tetrahedrons. All these things and my interest in printmaking led me to the generative aspect of repetition and the possibility of nuance and difference created along the road. I like unique repetition because it is the way we are. We are in one way a multiple and in another way, we are a singular entity.

All images courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista