Amidst his tightly packed itinerary, I had the privilege of meeting with Kengo Kuma. During his brief stopover in NYC, the interview, held at the Japan Society, offered a rare glimpse into the mind of one of the world’s most famous architects. Kuma’s insights transcended mere discussions of architecture; they delved into the ethos guiding his firm, which has spearheaded transformative projects across 40 countries. His multifaceted commitments encompass not only architectural innovation but also speaking engagements, educational initiatives, and groundbreaking research endeavors.

Kengo Kuma, born in 1954 in Yokohama, Japan, is a globally renowned architect whose work is deeply rooted in Japanese tradition and a profound understanding of materials. He graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1979 and pursued further studies at Columbia University.

In 1990, he founded his firm, Kengo Kuma & Associates, which has since evolved into a multinational practice with projects spanning more than 40 countries.

Kuma’s architectural philosophy revolves around the idea of seamlessly integrating buildings with their surroundings, emphasizing materials that reflect the local context and culture. He criticizes what he terms the “objectification” of architecture, advocating instead for designs that harmonize with their environment. This belief is evident in his seminal work “Anti-Object: The Dissolution and Disintegration of Architecture” (2008), where he challenges the notion of architecture as separate from nature.

Throughout his career, Kuma has championed the use of traditional Japanese materials such as wood, bamboo, stone, and ceramics, often employing innovative techniques to showcase their inherent beauty and sustainability. His designs emphasize lightness, transparency, and spatial fluidity, creating immersive experiences that foster a profound connection between occupants and their surroundings.

Notable projects by Kengo Kuma include the Japan National Stadium in Tokyo, the Suntory Museum of Art in Tokyo, and the Asakusa Culture Tourist Information Center. His portfolio ranges from small-scale structures like meditation houses to large-scale urban developments, each reflecting his dedication to enriching the human experience through architecture.

In addition to his architectural practice, Kuma is a prolific writer and educator. He has authored numerous books and articles on architecture, urbanism, and design, and has taught at prestigious universities worldwide, including Columbia University, the University of Illinois, and the University of Tokyo, where he currently holds the position of professor emeritus.Kuma Lab is a research laboratory led by Kuma, based in the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering at the University of Tokyo’s Hongo Campus, established in 2009. In 2012, Kuma Lab published the book “Patterns and Layering: Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature, and Architecture,” featuring research from various doctoral candidates. The lab’s research encompasses a broad range of topics, including architectural, urban, community, landscape, and product designs, as well as methodologies for sustainable design bridging physical and information domains. Activities include participation in architectural design competitions, organization of regional and international design workshops, joint research with other university departments, and proposals to aid in the recovery from the Great East Japan earthquake.

Kengo Kuma’s contributions to architecture transcend his built works; his design philosophy, centered on a dialogue between nature, technology, and humanity, continues to inspire architects and designers globally, shaping the future of the built environment with sensitivity and innovation.

An Interview with Kengo Kuma

By Carol Real

Your architecture is often described as a harmonious blend of nature and technology. How do you integrate these aspects and what inspires you to create such connections?

I aim to establish an intimate relationship with the environment in my architectural endeavors. In the 20th century, many architects sought to separate the environment from the architecture, exemplified by structures like the Centre Pompidou. However, I endeavor to bridge this gap by embracing environmental design principles. We achieve this by utilizing natural materials, which serve as the foundation of the natural environment, thereby fostering harmony with our buildings. Additionally, we prioritize the dimensions of our buildings relative to their surroundings. By aligning the size of our structures with the natural scale of the environment, we can seamlessly integrate them into their surroundings. This continuity of scale is paramount in our design philosophy.

In your book Anti-Object you criticize the idea of “objectification” in architecture. Could you elaborate on how your work challenges this concept and what alternative form of architecture you propose?

Yes, in my book Anti-Object, I critique the concept of “objectification” in architecture. My work challenges this notion by prioritizing continuity and interconnectedness over discrete objects. I aim to transcend the conventional separation between objects and their surroundings. While some may seek iconic architectural forms, I advocate for a synthesis with the natural landscape, drawing inspiration from topology. This approach considers the inherent qualities of the site, whether it be the contours of a mountain, the fluidity of a body, or the vitality of living organisms. By merging iconic elements with the environment, we create spaces that resonate harmoniously with their surroundings.

Your use of light in your designs aims to achieve “spatial immateriality.” Could you explain how you manipulate light and natural materials to create this effect, and why it’s important in your architecture?

Light is pivotal in our designs because it imbues materials with life and spirit. Natural light breathes vitality into the very essence of a material. Without it, materials remain in darkness, devoid of expression. Furthermore, natural light is dynamic, continuously shifting over time–from the gentle glow of morning to the warm hues of evening and from the crisp brightness of summer to the subdued tones of winter. We endeavor to capture the exquisite interplay between natural materials and this ever-changing light, showcasing the beauty of their harmonious composition. This dynamic relationship between light and material forms the most captivating aspect of architecture, and we strive to celebrate and accentuate this inherent beauty in our designs.

Many of your projects feature natural materials like wood, stone, and bamboo. How do you choose these materials for your designs, and how do they contribute to the overall aesthetic and experience of your buildings?

The definition of a natural material is ambiguous. For example, we often use rice paper. Rice paper is not a natural material itself; craftsmanship works together to create rice paper. However, in rice papers, we can find textures similar to glass materials. My concern is what constitutes a natural material. I want to emphasize the importance of natural materials to people because industrial materials were protagonists in modernism. Modernist architecture prioritized beautiful shapes but often showcased the beauty of industrial materials. I pursue the opposite direction and avoid industrial materials as much as possible. Sometimes we use concrete for foundations, hidden within the structure. Nonetheless, I don’t want to showcase concrete because its texture lacks a magical sensibility. We strive to adopt a modern building approach that emphasizes natural materials.

Could you describe a specific project where you faced challenges related to using local materials, and how you overcame them?

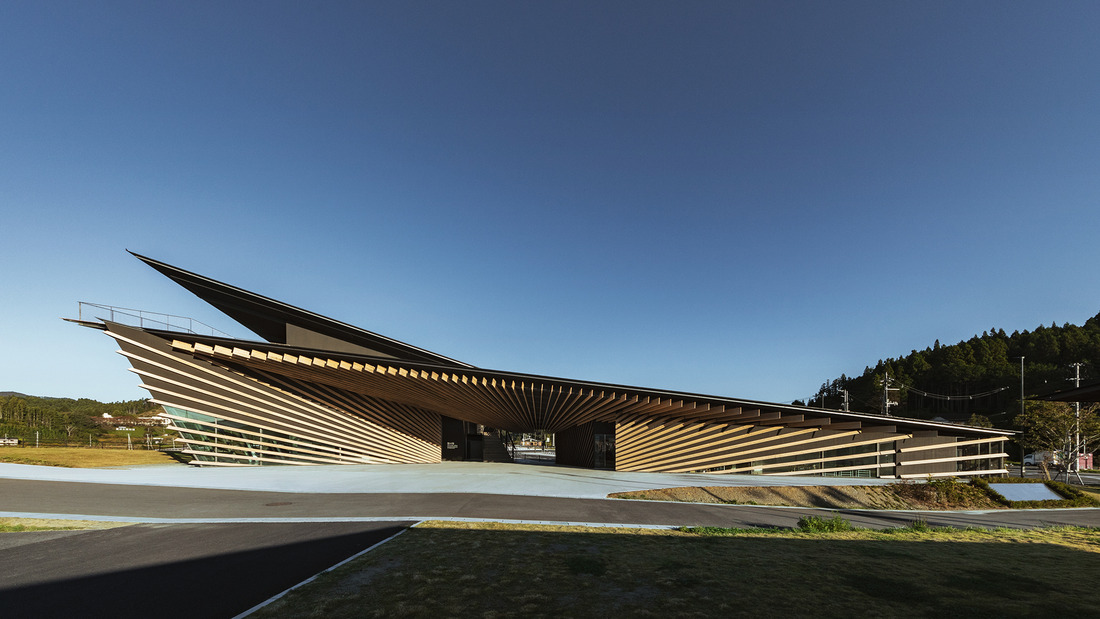

One notable example is the building project in Yusuhara village, Japan. Yusuhara is a small village known for its forestry industry. Despite its size, the village boasts six buildings that we designed. Given the community’s strong reliance on forestry, with their livelihoods deeply intertwined with the beauty of the forests, it was crucial to incorporate locally sourced materials into the design. Wood, being the foundation of their lifestyle, was the primary material used in every aspect of the project. This decision not only showcased the intimate relationship between natural materials and the local culture and economy but also ensured that the buildings seamlessly integrated into the fabric of village life.

Your architecture is often associated with an aesthetic that exudes tradition and “Japan-ness.” How do you navigate the balance between tradition and innovation in your work?

We draw inspiration from Japanese tradition not out of mere nostalgia, but rather out of profound respect for its underlying principles. Japanese tradition, rooted in reverence for harmony and sustainability, offers invaluable lessons. For instance, sustainable forestry practices, where trees are replanted every 60 years, exemplify a natural cycle that sustains not just the environment but also the economy of life. While the traditional architectural style is undoubtedly beautiful, our goal is to avoid mimicking it superficially. Instead, we strive to encapsulate the essence of this sustainable system and introduce it to a global audience. Japanese tradition, with its centuries-old sustainable practices, provides invaluable insights for the 21st century, where sustainability is paramount. This tradition has thrived for over 20,000 years, adapting to Japan’s challenging natural conditions—its rugged terrain, frequent earthquakes, and more. It stands as a testament to the efficacy of sustainable systems, offering profound lessons that resonate far beyond Japan’s borders.

You’ve mentioned the importance of studying a site to integrate a project with its surroundings. Can you share some practical examples of how this approach has influenced your designs and their impact on the environment?

As an architect, the principle of respecting and integrating with nature is fundamental to my approach. Unlike some European systems where there’s often a sense of control over nature, in Japan, we understand the inherent strength of nature. The frequent earthquakes remind us of nature’s power, and in comparison, humans are small and fragile. This understanding profoundly influences our design philosophy. We strive to learn from nature’s resilience and adaptability. In Japan, we have numerous examples of architectural designs that harmonize with nature. My goal is to translate these learnings into contemporary designs. Throughout my career, I’ve had the opportunity to work on a wide range of projects, from small meditation spaces to towering skyscrapers.

How do you adapt your design philosophy to accommodate the varying scales of architecture, and what challenges or opportunities arise from these differences?

At its core, design is about the relationship between individuals and their environment. Take, for instance, the Tea House—a serene sanctuary where only a handful of people gather in a cozy space. Here, we craft an intimate connection between occupants and surroundings. Conversely, consider a project like the Budda Towers nestled within a bustling urban landscape. Here, the design is defined by its interaction with neighboring structures and the bustling streets below. Despite the vast contrast in scale, the underlying principle remains consistent: prioritizing the relationship between elements.

In every project, whether small or grand, we emphasize this relational approach. Our designs do not stem from personal ego but rather from a deep understanding of and respect for the connections between spaces, people, and their context. Both small and large scales present unique challenges and opportunities, each contributing to the richness of our design process.

Your firm, Kengo Kuma & Associates, has projects in over 40 countries. How do you adapt your design philosophy to diverse cultural contexts?

We enjoy researching the environment in new places. We immerse ourselves in the setting when commissioned to design for a new location and client. We conduct thorough research and engage in conversations with the local community. This process allows us to discover unique relationships between humans and their environment, which in turn inspires our design approach. If we were to replicate projects in the same location, it would lack excitement. We thrive on the challenge of creating something fresh and innovative. Despite having worked in numerous countries, each project continues to inspire and impress us. Designing for new places is paramount in our work.

How frequently do you encounter instances where you need to reject a project?

Sometimes, the project is entirely new, while other times, clients simply want to leverage our brand name. Occasionally, they express that they don’t necessarily require a new design but are content with using one of our existing designs. When I sense this sentiment, I opt not to proceed. However, it’s ultimately my decision.

You’ve had a long academic career alongside your practical work. How has your teaching and research influenced your architectural practice and vice versa?

Well, indeed, for more than 30 years, I’ve been deeply engaged in teaching while concurrently pursuing practical work. My approach involves immersing students in new environments, often through travel. I find that traditional campus settings can lack the vibrancy necessary for stimulating creative thought. Therefore, I frequently organize trips with students to places like Taiwan, China, and the tranquil beaches of Japan. These journeys provide invaluable experiences and inspiration, offering numerous insights for students to absorb.

Another aspect of my teaching methodology involves hands-on construction projects. While students are adept at drawing and rendering, many lack practical experience building structures. To address this gap, I initiate pavilion projects that start from initial sketches and progress to physical construction. This hands-on approach presents a significant challenge for students as they grapple with unfamiliar materials and construction techniques. However, upon completing these projects, students not only gain practical building skills but also develop a deeper understanding of architectural design and implementation.

In essence, my teaching philosophy revolves around providing students with immersive experiences and practical challenges, equipping them with the skills and knowledge necessary for success in their future endeavors.

How do you envision the future of urban development, especially in rapidly growing cities? Can your design philosophy be scaled up to accommodate the needs of large urban populations while maintaining a deep connection with nature?

In light of the post-COVID landscape, our approach to urban development is undergoing a significant shift. Previously, the trajectory was towards increased density, with a focus on towering skyscrapers and high-density living. However, the pandemic has prompted a reassessment of this model, with many individuals expressing a desire to move away from densely populated areas in search of more space and a connection with nature. As such, there is a growing need for urban design that facilitates this kind of escape, providing alternative living environments that offer both safety and a sense of sanctuary. Our design philosophy acknowledges this shift and seeks to create spaces that not only accommodate large urban populations but also prioritize harmony with the natural world, offering residents the opportunity to thrive in a more balanced and sustainable environment.

Lastly, Mr. Kuma, could you please share your insights on the most significant challenges that the field of architecture is anticipated to confront in the upcoming years?

We have decided to break away from the traditional large office setting in Tokyo, where our main office currently resides. Our goal is to escape the confines of the big city, which has led us to establish four small satellite offices in different parts of Japan: in the North in Hokkaido, in the South in Okinawa, in the mountains, and by the beach. While this decentralization may pose communication challenges at times, it has fostered a close-knit community within each satellite office. We typically send around 33, with a maximum of eight individuals, to these locations, where they immerse themselves in the local culture and enjoy close communication within each small community. This new working style represents a shift in the role of architects in the future, where our mission is to collaborate closely with communities and support local craftsmanship. Our satellite offices serve as examples of this mission in action.

Photo credit: Courtesy of © Kengo Kuma & Associates

Editor: Kristen Evangelista