Artist’s Biography

Jorge Macchi was born in Buenos Aires in 1963 and has firmly established himself as one of Argentina’s foremost contemporary artists, celebrated for his diverse and thought-provoking contributions to the world of art.

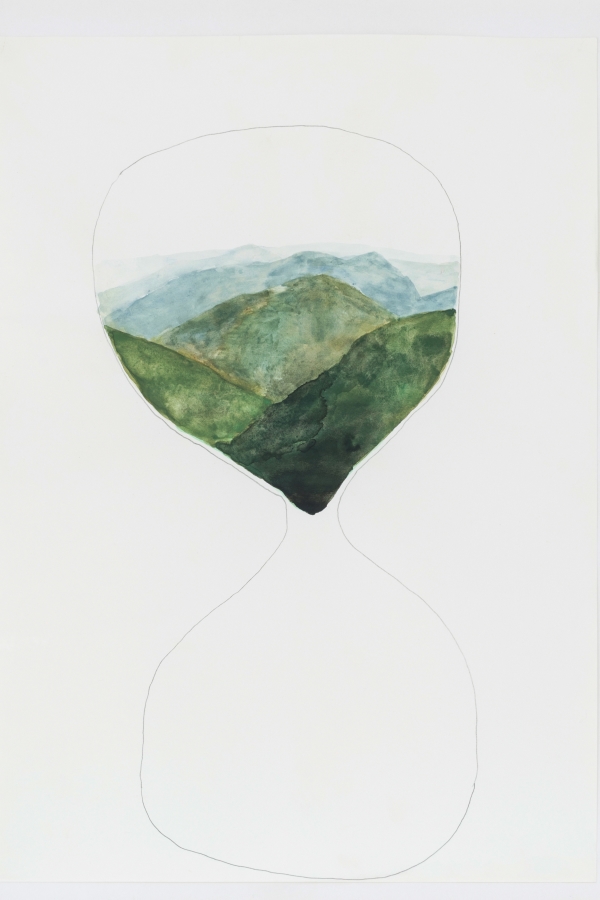

Macchi’s artistic journey spans a wide range of mediums, including sculpture, painting, installation, video, and conceptual and performance art. At the core of his creative process lies a deep fascination with the potency of imagery. Often, Macchi initiates his artistic endeavors with a simple drawing, capturing the unexpected encounters and surprises that punctuate daily life. These initial sketches evolve into exquisite drawings or watercolor sketches for some, while others transform into three-dimensional sculptures or compelling video installations.

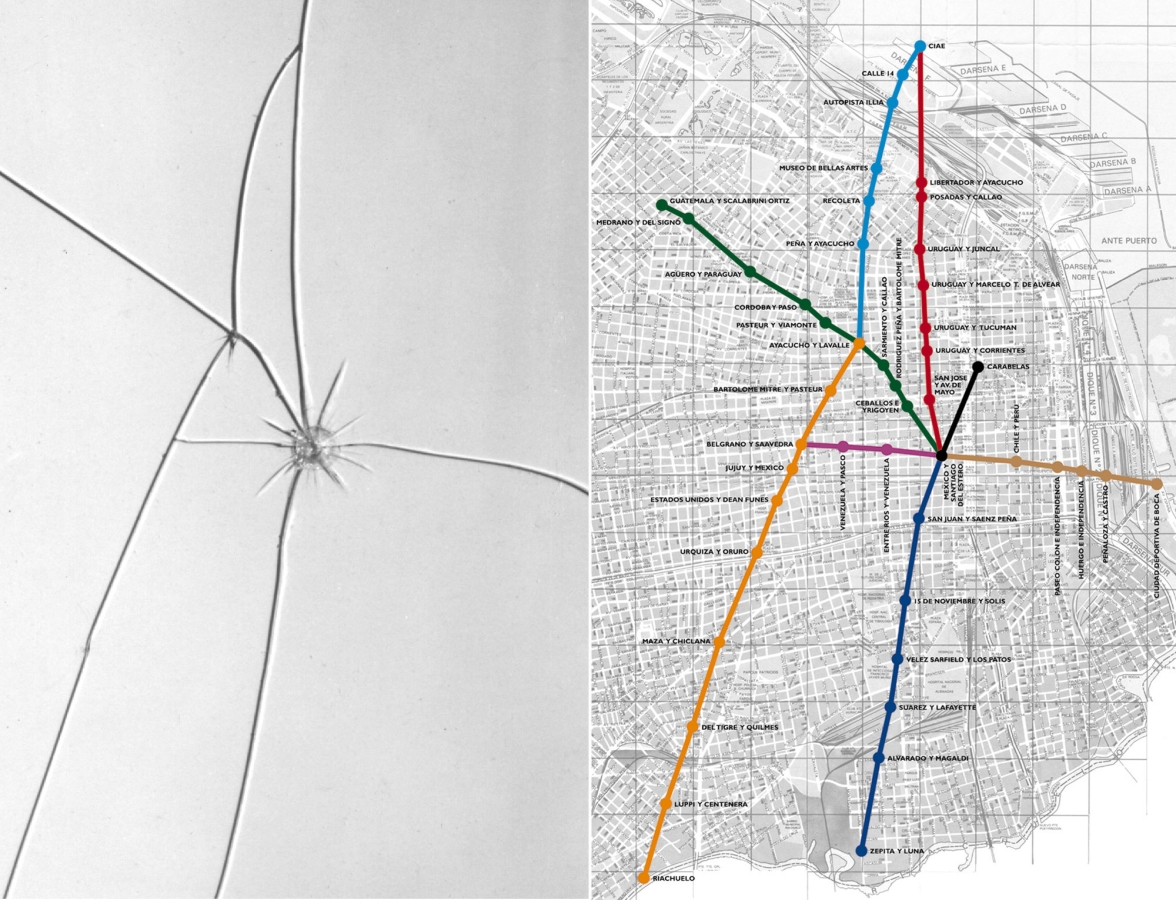

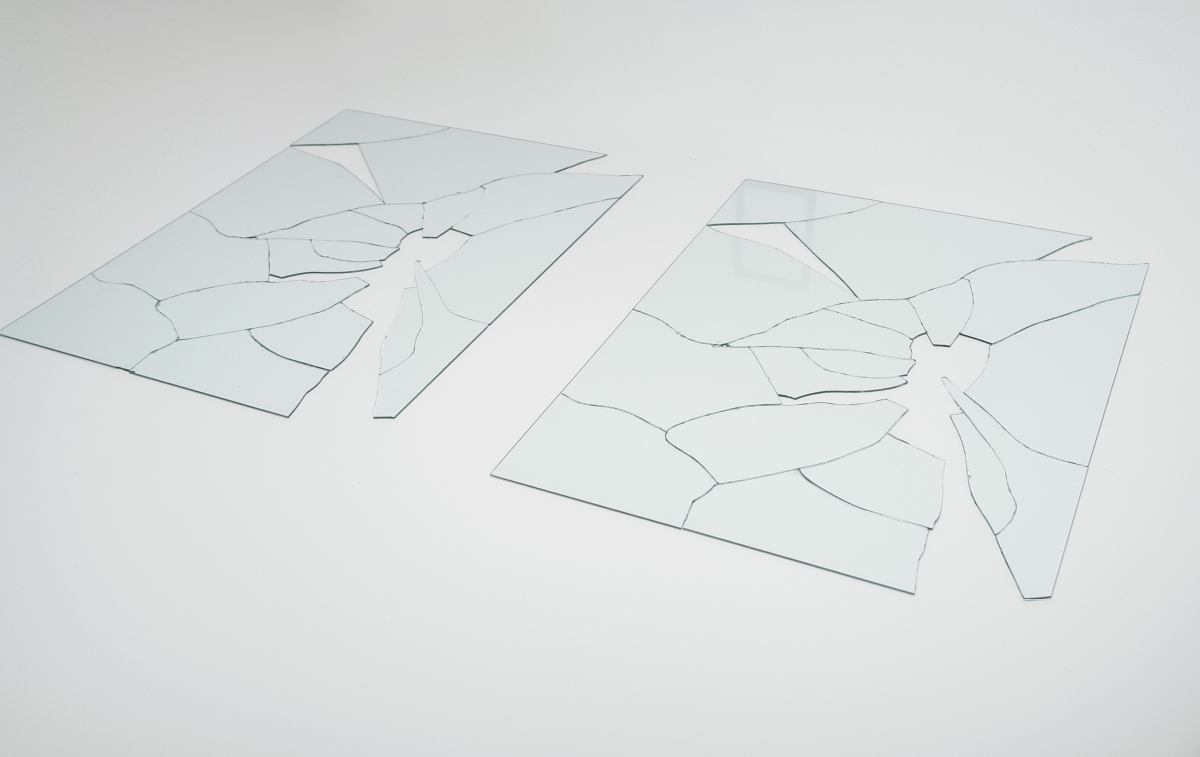

Macchi’s work is characterized by its embrace of chance and the accidental. He frequently incorporates readymades, such as newspaper clippings, city maps, and sheet music, into his creations, infusing his art with elements drawn from everyday existence. Notably, in his collaborative work “Buenos Aires Tour” (2003), Macchi cracked a pane of glass over a city map to determine a random path through the urban landscape. He incorporated music, sounds, and other materials encountered along the way to construct an alternative tour of the city.

The influence of avant-garde figures like John Cage and Jorge-Luis Borges is evident in Macchi’s work, showcasing his commitment to pushing the boundaries of conventional artistic expression. His innovative video piece “Caja de música” (2003-4) ingeniously transforms aerial footage of a six-lane highway into an automatic musical instrument, highlighting his profound connection to music and its interpretations.

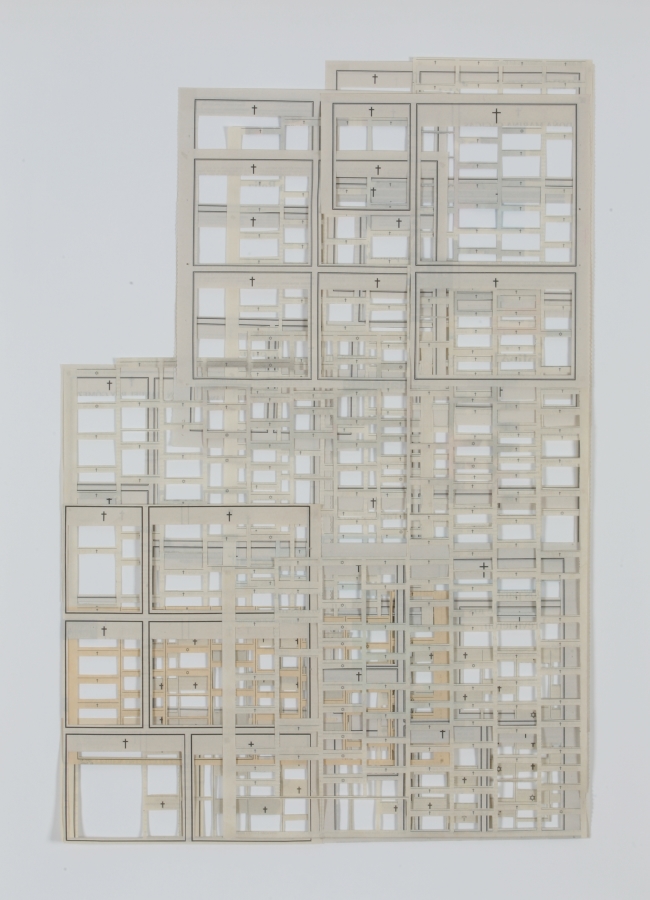

Macchi’s exploration of text as an artistic medium is exemplified in his thought-provoking work “Monoblock” (2003), where he extracts text from obituaries, leaving only crosses, Stars of David, or crescent moons to signify the religion practiced by the deceased. This results in a contemplative collage of newsprint, resembling the shape of an apartment block.

Drawing upon his own experiences, Macchi’s work often carries autobiographical undertones. He studied piano during the tumultuous years of Argentina’s military dictatorship, and this period has profoundly influenced his artistic perspective. His sculpture, characterized by five lines formed by rope held taut by springs, can be interpreted as a musical staff devoid of notation, symbolizing enforced silence or the struggle to convey the ineffable. This sculpture juxtaposes the soft form of a pillow, a symbol of intimacy, against the rigid wall, creating a dialogue between order and the transcendence of bodily boundaries.

Jorge Macchi’s artistic journey has been adorned with numerous accolades, including a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship, his participation in over a dozen biennials, including those in Venice and Sydney, and his involvement in collective exhibitions at renowned institutions such as the Walker Art Center and the Hammer Museum. Furthermore, he has had a retrospective at the Blanton Museum.

In a world where art serves as a bridge between the tangible and the intangible, Jorge Macchi’s work stands as a testament to the power of visual expression, chance, and the enduring influence of personal experiences. His art captures the ephemeral and the transient, inviting viewers to reflect on the fragile boundaries that define our existence.

Interview Artist

Jorge Macchi

By Carol Real

How did your education at the National School of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires influence your artistic perspective?

I attended the School of Fine Arts during a period of transition between dictatorship and democracy. For this reason, absolutely archaic content coexisted with chaotic attempts at modernization. What I value from that time is not so much what I learned from the teachers but the contact with other artists who were in the same situation. I consider that to be the real artistic education.

Jorge Macchi, your work spans various mediums, from sculpture to video and installation. Can you share how your creative process evolves through these different forms?

In general, the works originate from an image or a convergence of images. At that moment, I need a drawing to capture that image on a support, something very simple. From that point on, I think and choose the materials and techniques that allow for the greatest expansion of that image. Perhaps for that reason, I don’t usually work with predetermined images, materials, or techniques.

You mentioned that everything starts with an image for you. Could you elaborate on your approach to finding and developing these captivating images?

Generally, while walking down the street, that’s when the images appear. But, as I mentioned before, it’s not just the image itself, but the encounter with that image and others that I have stored or recorded. And generally, I shouldn’t have the will to find it in order to do so. For me, as for most artists, the smartphone is a fundamental working tool.

Your work often addresses the theme of time. How do you capture and convey the essence of time in your art?

I’m not sure that the central theme is necessarily the passage of time. Instead, I believe my work primarily focuses on the duality between movement and stillness. I think of an image that I consider very significant: movement arises from multiple successive moments of stillness. This notion reflects the paradox present in cinema, which remains relevant and enriching for me.

How do you utilize the concept of chance and serendipity as creative tools in your work?

Chance and the accidental are fundamentally themes, which are a support or constructive structure for my works. It’s a controlled randomness, a rather Duchampian attitude. It’s opening up the possibility for a chance to appear. I don’t feel that there is a real experience of the accidental since I am too obsessive to let it be completely free. Interestingly, it is in painting where I truly experimented with chance.

In “Buenos Aires Tour”, you broke glass over a map of the city to determine a random path. How does this process challenge traditional notions of navigation and exploration?

It’s quite complex to answer this question. Buenos Aires Tour takes the format of an alternative tourist guide and arose from the moment I decided that Buenos Aires would be my definitive base, my place to live and work. This decision, seemingly simple, contains many contradictions. The question was: how to portray a city that I know deeply but cannot truly comprehend? Chance then became the fundamental tool of that book since I didn’t want to determine the routes of that possible tour. The objects, images, and sounds found at each of the “tourist points of interest” are also the result of chance and generally do not provide information about that place; instead, they are traces of the people who passed through those points. As Buenos Aires Tour does not aim to inform, I feel that there is information that emerges despite it all. I couldn’t put that content into words, but I know it exists. One of the most significant objects I found during the process was a hand-written English-Spanish dictionary, very weathered. I thought that the notebook had the same pretension as typical tourist guides: just as a city cannot be understood simply by accumulating geographic, historical, and sociological data, one cannot access a language simply by understanding the meaning of its words. https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/99/buenos-aires-tour

John Cage and Jorge Luis Borges are influences in your work. Can you explain how their ideas have shaped your artistic practice?

I could say that in the case of John Cage, chance is as important as emptiness. Perhaps one could say that chance reveals emptiness. In Borges, there is no chance; everything is obsessively constructed. However, it is a delicately crafted construction to reach emptiness.

Your art often incorporates everyday materials like newspaper clippings and sheet music. How do these found objects contribute to the narrative of your pieces?

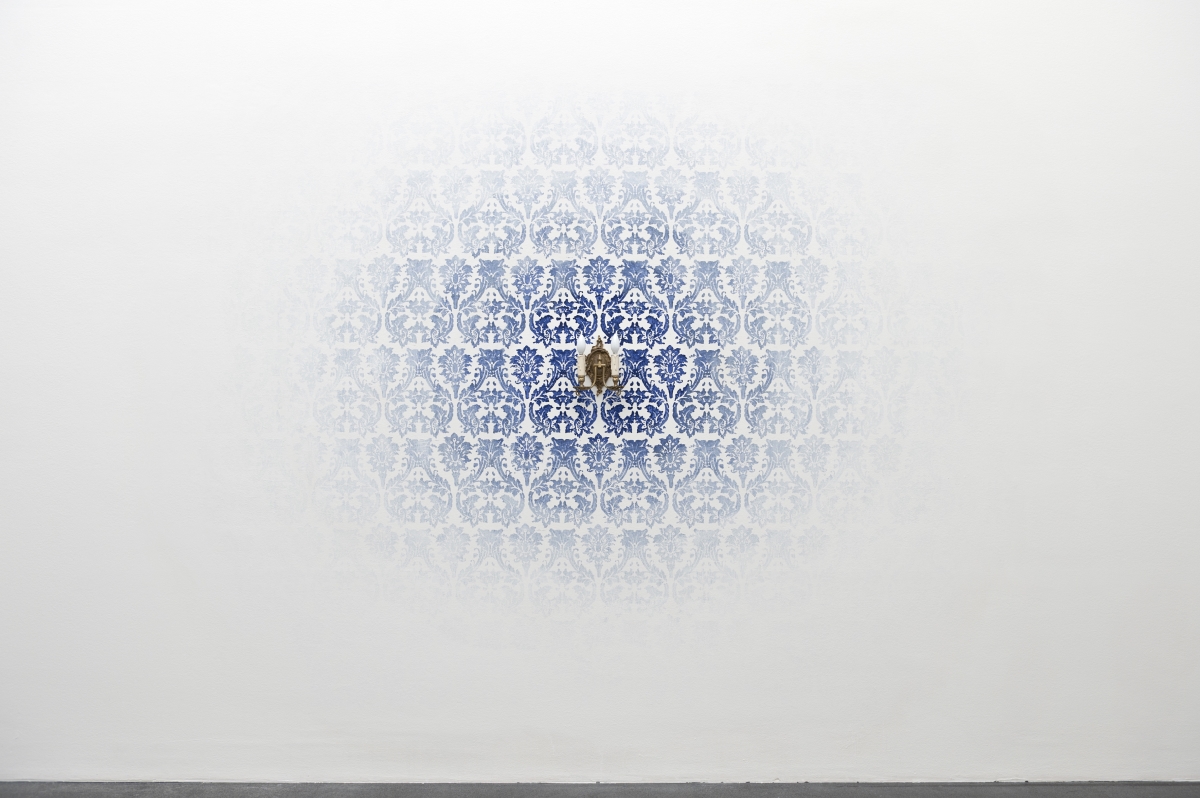

I worked with those materials mainly at a time when people still read physical newspapers. Nowadays, almost nobody buys newspapers, and for that reason, I lost interest in them. In general, I worked by subtraction: I removed the texts and images from the pages, and in that way, the paper, which was simply a support, became the protagonist. At the same time, the paper weakened, and the air passed through it. It became a dead leaf, highlighting its weight and fragility.

Could you share more about your interest in music and its representations, as seen in works like Caja de música and Music Stands Still?

I believe that images are more susceptible to translation than music. This, of course, is debatable. I can describe in words what is seen in Caja de Música: a group of cars moving along a six-lane avenue. I can also describe what kind of sound accompanies this image. What I cannot do is describe the music itself. That is precisely the dimension that music incorporates into my works: the ungraspable in the face of the triviality of the image. And there is something important in this coexistence: there is no subordination of one language to the other; there is a horizontal relationship between them. The way I usually collaborate with musician Edgardo Rudnitzky is based on that certainty. https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/245/musical-box

Can you tell us more about your experience studying piano during the military dictatorship in Argentina and how it influenced your artistic career?

I started studying piano at the age of 15, and I don’t really know why I wanted to study it. But I studied it intensively and managed to play some pieces that satisfied me. However, since I had a hard time reading music, I was forced to compulsively repeat my entire repertoire every day, partly because I enjoyed doing it, but also to avoid forgetting the pieces and having to return to the torture of sheet music. At a certain point, this situation became impossible. My adolescence is reflected in this contradiction. It was a dark time, but my adolescence itself was dark, beyond the historical context. Nevertheless, I see that music is present in different ways in my practice as a visual artist, not only in those pieces where there is actually music. There are formal elements of music, such as rhythm, repetition, symmetry, and transparency, that are protagonists in my images.

Pasting police news articles into a musical staff to produce a random melody is a fascinating concept. How does this transformation of text into music work in your pieces?

“Incidental Music” is a piece from 1997. At that time, I was doing a residency at Delfina Studios in London and reading newspapers to improve my English. Unconsciously, I began collecting police news related to anonymous people–those kinds of stories that disappear from the newspaper the next day. I started pasting the texts onto a very large piece of paper, using them to draw the lines of an empty musical staff. But since I left a blank space between the end of one text and the next, these blank spaces eventually turned into musical notes that originated a five-minute piece for solo piano. So, the random distribution of tragic stories gave rise to this piece, which I considered incidental music for everyday life. In it, textual language and musical language coexist, and the contrast between the two is very powerful: tragic and violent stories coexist with simple (only five notes) and calm music. It is also the coexistence of gruesome figuration and sublime abstraction. Both coexist horizontally; there is no dependence between them.

https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/119/incidental-music

In The Ascension, you transform sheet music into a dynamic presence. Could you delve into the concept of defying gravity in your art?

The Ascension was a performance and installation produced in collaboration with Edgardo Rudnitzky for the Argentine representation at the Venice Biennale in 2005. On that occasion, the building serving as the national pavilion was an 18th-century oratory with a mural on the ceiling depicting the ascension of the Virgin Mary. For the installation, I reproduced the shape and size of the mural frame in the form of a trampoline located directly beneath it. Rudnitzky composed a twelve-minute piece for viola da gamba and an acrobat. During the performance, the acrobat made regular jumps on the trampoline, creating a percussive effect that contrasted with the melodic line of the viola da gamba. Besides this musical coexistence, the piece was a dialogue between the two-dimensionality of the painting and the three-dimensionality of the object in real space. Simultaneously, it was a dialogue between the pictorial artifice, where characters float in the sky, and real space subject to the laws of gravity. There was something Sisyphean in the determination of the acrobat to repeat the same movement with the certainty of the impossibility of accession. https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/94/la-ascension

Your art is known for its sharp sense of dark humor. How does humor play a role in addressing deeper themes in your work?

Sometimes, I observe the reaction of visitors to my exhibitions. In some cases, I see a smile. Not a loud laugh, but a smile. I like it when that happens, just as I enjoy finding humor in artworks as a spectator. As an artist, I’m not very aware of this gesture; it simply satisfies me. It’s part of constructing an image. Humor allows me to be both inside and outside, and it acts as an antidote to pathos.

You often draw inspiration from newspapers and everyday life. What do you see as the intersection between art and reality in your work?

Everyday life and ordinary objects bridge the gap between the creator and the viewer. I need the viewer to know or be familiar with the materials I work with so that my gesture or opinion becomes visible. I don’t believe that art and life are a continuum; I advocate for the realm of artifice.

Your work reflects an interest in margins, endings, and fragments. Could you explain the importance of these themes in your art?

From the beginning of my career as a visual artist, I worked with discarded material. I was interested in manipulating what others discarded, what was cast aside. It was an attitude that had a political but also a sentimental component: those materials contained the history of what had happened to them. I could consider the crime stories of anonymous characters as a special type of discard: they are objects or materials that are on the fringe. But when the central element disappears, those margins take center stage. When the newspaper is no longer the medium for information, it becomes paper again, but with a history.

Your pieces often challenge systems of order. Can you discuss the tension between order and chaos in your art?

Art is a realm of fiction. In this realm, every perfect, firm, and oppressive structure that surrounds us daily is susceptible to being subverted effectively and subtly. I believe in the political power of art, as long as that political intention is not deliberate, arising even without the artist’s awareness.

You are known for creating paradoxical structures in your art. What message or emotion do you hope viewers gain when encountering these paradoxes?

Paradox is the suspension of meaning. It is one of the forms of humor. It is one of Borges’ favorite tools. It is the word that defines much of what I do. The archer and the arrow, Zenon of Elea’s aporia, the scene in which an arrow aimed at a target never reaches it because the distance between them can be divided infinitely, is a paradox that has accompanied me forever. And I arrived at it through Borges. In an essay about the pre-socratic philosopher, he concludes: “Zenon is unassailable unless we confess the ideality of space and time… Does that touch upon our concept of the universe, by that tiny piece of Greek darkness?”, my reader might wonder. https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/253/la-flecha-del-zenon

Fim de Film is a video work in collaboration with composer Edgardo Rudnitzky. Can you share the creative process behind this collaboration and the role of music in your art?

This video is a continuation of Caja de música, inspired by my obsession with music boxes. I remember it all started on a flight. I was watching a movie, and after it ended, the closing credits began to roll. The lines of text made me think of the cylinder in music boxes. I thought that each of those lines could mark the pulse of a musical composition. When I started working with Edgardo, we had several things clear: the text of each line would not be legible (it would have a blurry effect), the sound of each beat would originate at the moment the line appeared at the bottom edge of the screen, and the music should resemble the typical music at the end of a movie, so that for a moment, the relationship between the image and the sound would not be clear. As the video progresses, that relationship becomes very clear. When I had my retrospective at Santander Cultural in Porto Alegre, we were able to work with the Porto Alegre Symphony Orchestra, which, for me, added coherence to the project. https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/229/fim-de-film-end-film

Your work often plays with the interdependence of verbal, visual, and sonic narratives. How do you find the balance among these elements?

In the late 90s, I started working on theatrical productions and worked intensely in that field for five years. Theater production is diametrically opposed to the solitary work of a visual artist. There is a convergence of knowledge towards a common goal; it is almost impossible to work alone. On the other hand, the relationship between different disciplines is horizontal; there is no, or there shouldn’t be, subordination of one to another. They work together in complementation. I believe that this theatrical experience was the origin of my collaborations with musicians or writers, and it was clearly reflected in the Buenos Aires Tour, where Edgardo Rudnitzky, María Negroni, and I worked collaboratively, complementing our specific roles.

Ten Drops is a flipbook that simulates concentric circles of drops falling on water. What inspired this exploration of stillness and movement?

The flipbook format is, in itself, a paradox that it shares with cinema: a series of consecutive still images create the illusion of motion. However, unlike cinema, in a flipbook, there’s the possibility to pause on each page and analyze each one. In Ten Drops, 10 holes gradually appear, piercing the physical book and reaching the back cover, and at the same time, these perforations create concentric circles simulating ripples in the water caused by the apparent fall of 10 drops. So, one perspective focuses on the artifice of movement, while another, more analytical perspective perceives that what causes that movement in the water remains in the book and transforms it. As in other instances, a dialogue occurs between the permanent and the ephemeral.

How do you perceive the role of your art in reflecting and shaping the cultural and social landscape of Argentina and beyond?

I consider that the function of art in reflecting reality or shaping a cultural landscape occurs unconsciously. The artist’s intention to reflect reality or shape a cultural landscape is necessarily bound to fail.

How do you navigate the fine line between abstraction and representation in your art?

I aspire to create an image that is formally powerful and conceptually deep. Each of these two ideas, separated from the other, makes no sense to me.

Could you describe the importance of your retrospective exhibitions in relation to your artistic trajectory and legacy?

Retrospective exhibitions are moments of reflection. They are intense experiences because they serve as confirmation or denial of the existence of a common thread running through works from different periods and formats. On the other hand, they raise the level of demand when returning to the studio. Inevitably, there is a loss of innocence.

Could you share some memorable experiences or encounters that have influenced your artistic practice?

Certainly, having known and seen memorable exhibitions by Cildo Meireles in São Paulo and Francis Alÿs in Mexico City. Also, an exhibition by Mark Manders at SMAK in Ghent. When I was just starting my career, I remember Guillermo Kuitca’s exhibition “Siete últimas canciones” at the Julia Lublin gallery in Buenos Aires in 1986. I also recall my encounter with the Dutch artist Marinus Boezem, long after his participation in the São Paulo Biennial in 1989, which had a significant impact on me.

Installation Height: 12 meters from the floor. Ausbildungszentrum Rohwiesen, Stadt Zürich.

Project: Kunst und Bau. Ph Jorge Macchi

How do you select titles for your works, and what role do they play in the viewer’s interpretation?

I believe there are different types of titles. Some titles merely identify the work and serve a practical purpose, especially for the artist who created it. There are bad titles in the sense that they provide content that the work couldn’t resolve visually. And there are specific and appropriate titles in the sense that they provide ongoing feedback with the image. I definitely prefer the latter.

How do you approach the documentation and preservation of your ephemeral and multimedia works?

Regarding multimedia works, given their constant dependence on technological advancements, conservation methods are constantly evolving. While in the past, videos used to be stored on tapes, nowadays, everything comes down to digital files, which carry certain risks. For this reason, I choose to preserve all the materials used in the creation of a work. As for ephemeral works, in general, I maintain a record that includes high-quality photographs of the installations, precise measurements, material lists, detailed instructions, color samples, and any necessary information to reproduce the work in the future.

In Monoblock, you removed text from obituaries, leaving religious symbols. What statement were you making about memory and identity?

I am against making a statement. On the other hand, I am a strong advocate for the power and specificity of visual language. So, when I created that artwork, I wasn’t making any statement that could be translated into text. I had the certainty of the specificity of the image, but I couldn’t, and still can’t, determine the basis of that certainty. I prefer things to be that way and leave them in a state of suspension.

https://www.jorgemacchi.com/en/works/103/monoblock

As an artist, what motivates you to constantly explore new ideas and media, and how do you envision the evolution of your work in the future?

I see no sense in getting stuck in a single format, material, or image. In general, I am more attracted to artists whose works I can’t immediately identify through the presented image, as I value surprise. This approach is also reflected in my artistic production. I easily get bored, and boredom acts as a powerful search engine in my creative process. I aspire to have viewers continue to perceive an underlying thread despite the diversity of topics, formats, techniques, and images I employ, even if I myself don’t recognize it. In fact, I would prefer not to recognize it.

(1) Jorge Luis Borges, “La perpetua carrera de Aquiles y la tortuga,” Discusión, 1932.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

More imgages: