Joan Semmel (b. 1932) has centered her practice around representations of the body from the female perspective. Born in the Bronx, NY, she studied at The Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, and the Art Students League of New York. Trained as an Abstract Expressionist in the 1950s, Semmel began her painting career in Spain and South America. Returning to New York in the early 1970s, she turned toward figurative painting, constructing compositions in response to censorship, popular culture, and concerns around representation. Her practice traces the transformation of women’s sexuality over the last century, emphasizing the possibility for female autonomy through the body.

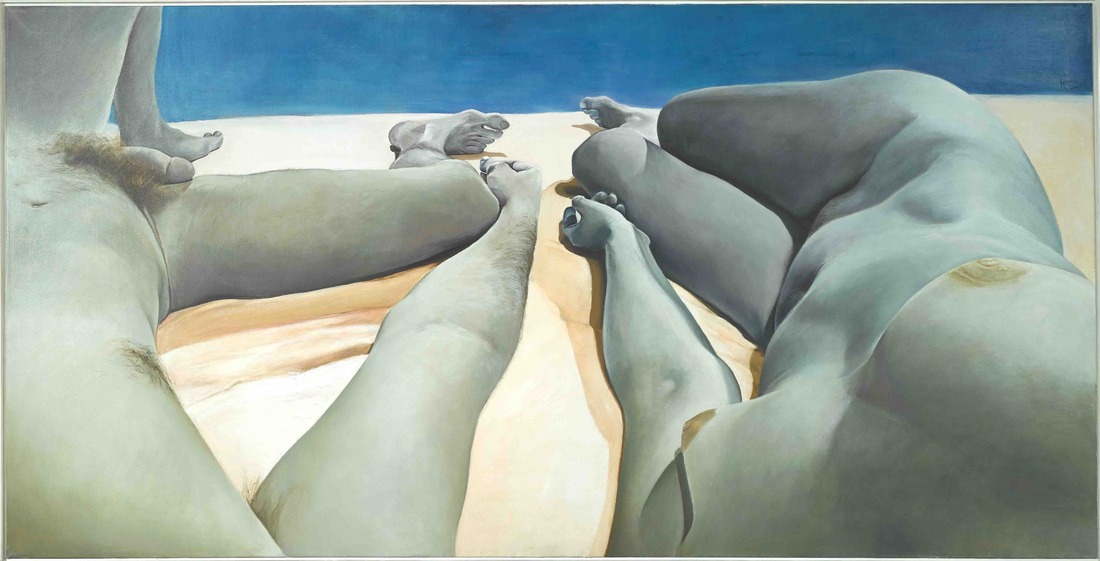

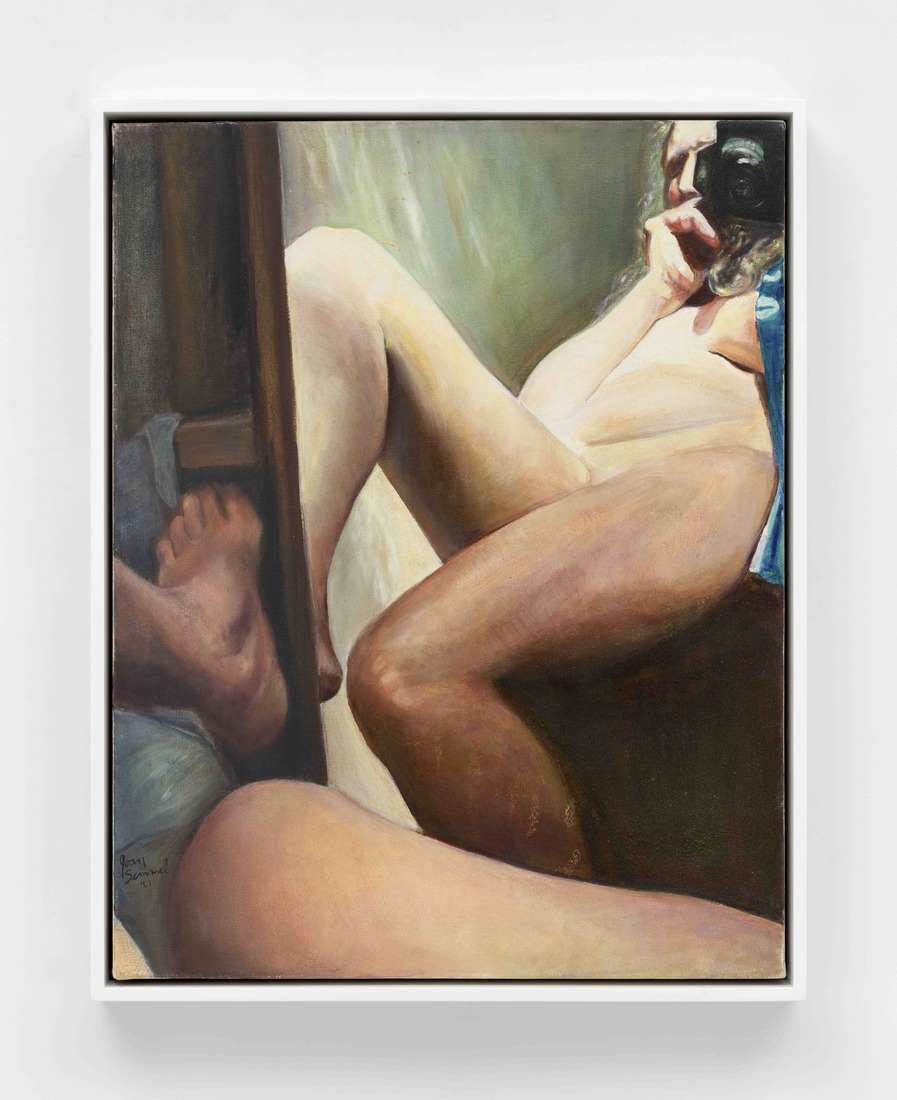

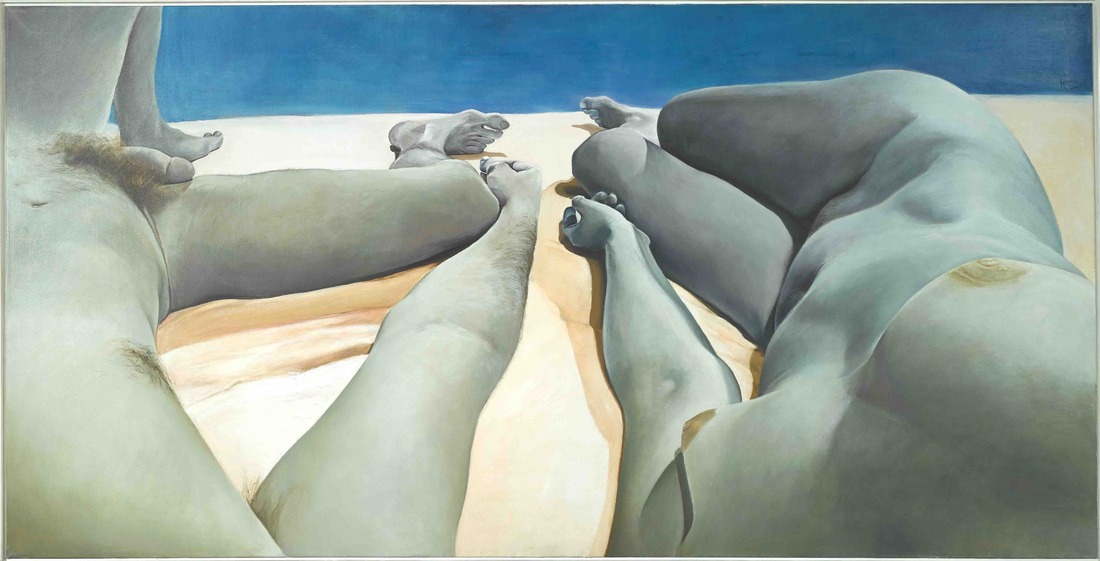

In the 1970s, Semmel began exploring female sexuality with her *Sex Paintings* (1971) and *Erotic Series* (1972). In these large-scale works, she employs expressive color and loose, gestural brushstrokes to depict couples entwined in various intimate positions. Produced in a cultural landscape shaped by second-wave feminism, these series celebrate female sexuality, heralding a feminist approach to painting and representation. In 1974, Semmel radically shifted her practice, adopting her own body as the focus of her paintings. With this shift, she transformed her point of view from that of an observer—a viewer outside of the canvas—to that of both an observer and subject. Using a camera to frame her body, she created a series of paintings reflecting her commitment to marrying abstraction with realism. In the 1980s, Semmel built on these works, painting dynamic scenes featuring her camera and body reflected and refracted through mirrors.

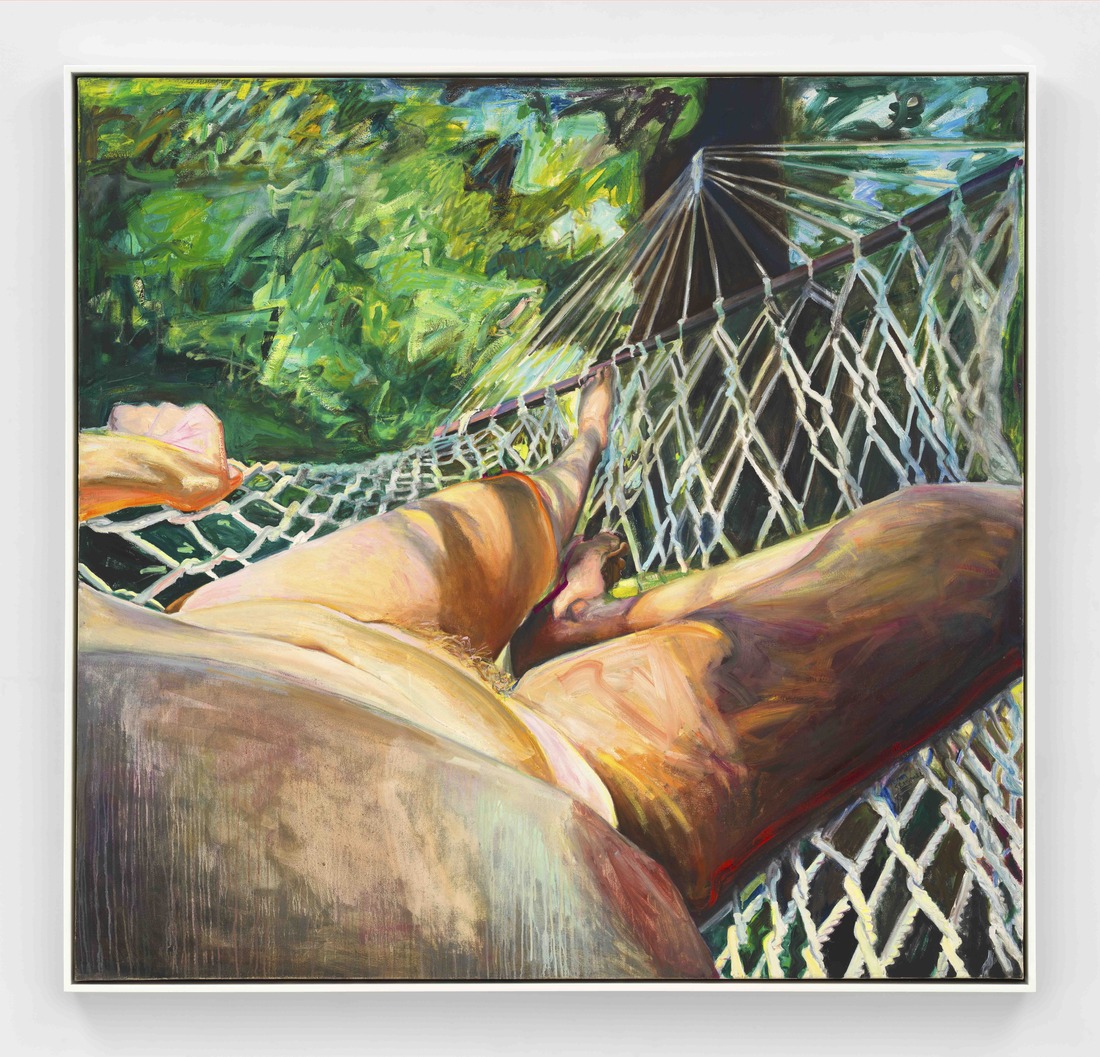

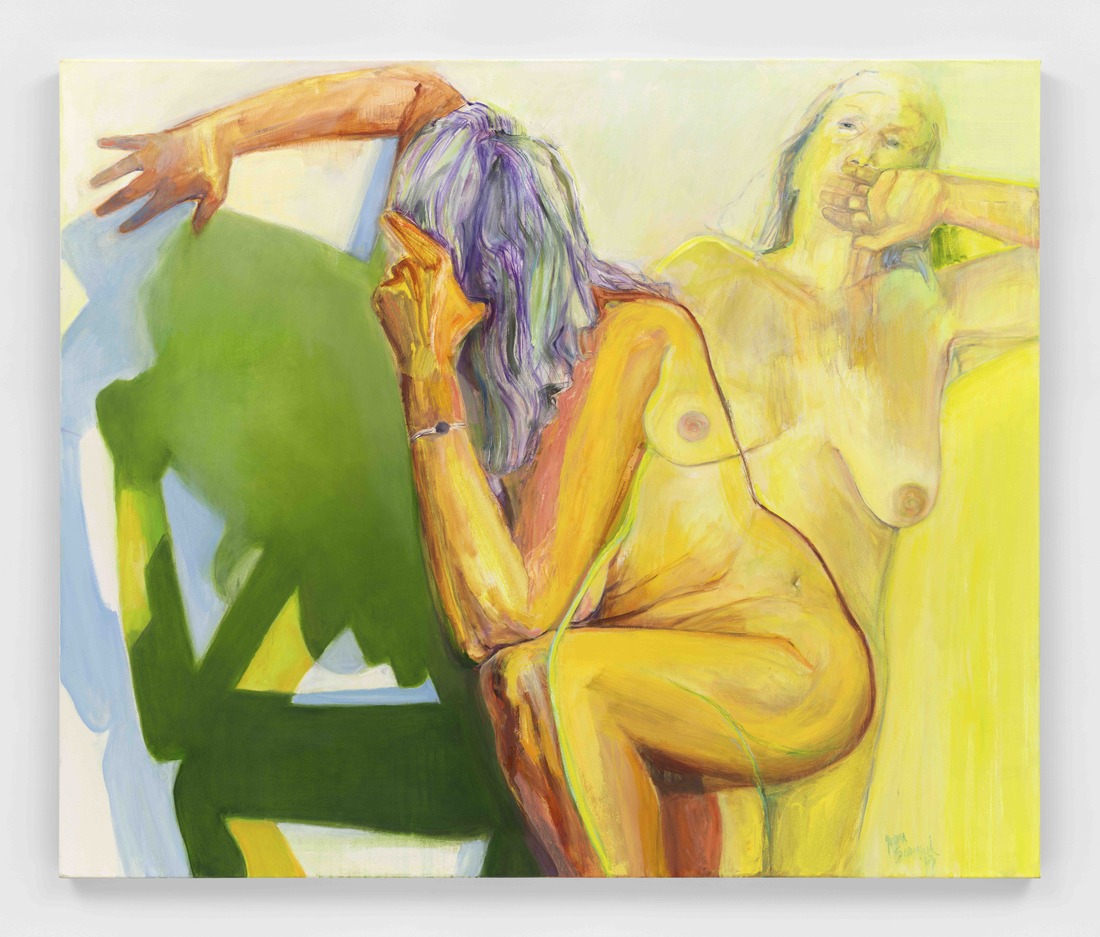

Since the late 1980s, Semmel has meditated on the aging female physique. Continuing her exploration of self-portraiture and female identity, her recent canvases represent her body doubled, fragmented, and in motion. Her gestural technique and palette of intensely saturated and diluted hues often blur the distinction between representation and abstraction, occupying a liminal space in which flesh is transfigured into pure pigment. Approaching her own form as a site of self-expression, she challenges the objectification and fetishization of women’s bodies by redefining the female nude through radical imagery that celebrates the aging process—refuting centuries of art historical idealization.

Semmel was the subject of a career retrospective, *Skin in the Game*, presented by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA, in 2021, followed by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, in 2022. In 2024, her work will be featured in group exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA, and the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, CA. Semmel’s work has been presented at Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom (2023); Brooklyn Museum, NY (2023 and 2016); The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY (2020); Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken, Germany (2018); The Jewish Museum, New York, NY (2018 and 2010); Whitney Museum of American Art, NY (2016); The Museum of Modern Art, NY (2014); National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. (2014); The Bronx Museum of the Arts, NY (2013); Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Arnhem, The Netherlands (2009); and Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH (2008), among others. The artist’s paintings are in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL; Brooklyn Museum, NY; Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA; The Jewish Museum, New York, NY; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX; The Museum of Modern Art, NY; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.; Tate, London, United Kingdom; and Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, among others. She is the recipient of numerous awards and grants, including the Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award (2013), Anonymous Was a Woman (2008), and National Endowment for the Arts awards (1985 and 1980). She is Professor Emeritus of Painting at Rutgers University.

Bio:Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates

An Interview with Joan Semmel

By Carol Real

Reflecting on your significant career, how has your artistic voice evolved from your early abstract expressionist works in Spain to your current self-portraits? Can you identify specific moments or experiences that were major turning points in your artistic journey?

My work over the years has crossed many boundaries of style and content, but there is a consistency of intent and execution. The earliest abstractions were an exercise in paint handling and color manipulations to achieve the illusion of space on an acknowledgedly flat surface. The later abstractions began to incorporate structure and, at times, symbols, while always striving to create a sense of presence in the work and possessing the power to captivate the viewer in that moment of discovery. After working and exhibiting in Spain, where I lived for seven and a half years, I returned to NYC, and my work underwent a radical transformation. I needed to find a way to express the energy and intent of my life at that time. I had never worked with representational form or content and was involved with the current political ferment of young people in the NYC art world. I wanted to find a way to unite my art with my life, so I chose to begin using the figure. The first images were openly sexual with expressionist color and gesture. As I moved to the camera for the image, the work became more realistic, but I wouldn’t give up my use of high color, and that always remained abstract. After two exhibitions of work exploring sexuality, I turned the camera on myself to create self-images. They have never been intended as self-portraits. I used myself and my body as symbolic icons for making a political statement as a woman, insisting on the woman as an artist defining her own image, asserting agency, and refusing objectivity.

How have your core themes—such as the exploration of the female body and sexuality—remained consistent, and in what ways have they transformed over the decades?

I chose to focus on sexuality as a theme in my work because it seemed necessary for women to express desire without shame. To change the culture so that women could participate on equal terms politically, the passive and dominant structure of relationships had to be reconsidered from sexual to familial, and one had to begin at the beginning. When we are young, sexuality is most central. As one gets older, identity becomes more paramount, and then finally, if lucky, one must deal with age. My work passed through those phases without any forethought on my part. My most urgent desire has always been to not simply follow but to explore my own truth and find my own way.

What prompted your shift to using your own body as the primary subject in your work, and how has this approach evolved over the years?

When I decided to leave the sexual series and find another way to approach the theme, I had to find a way to use the nude without objectifying the woman. I thought that by using myself, I would not be doing that to another human being but would be giving the nude agency as the author of the action.

The first self-images were taken with a camera from my own viewpoint so that the distortions were recorded, and the head, of course, was not seen. The resulting images at times had connections both to abstraction and at times to landscape.

After a few years, I had exhausted that device but continued using myself as the subject. I turned to take images from the mirror so the image in the painting held a camera and faced the viewer. Robert Storr wrote, “Who was looking at whom?” in a catalogue essay he did on that work back then. I never thought of the works as “portraits.” I wasn’t after any statement about myself but rather simply needed a female protagonist, and I, of course, was always available.

I was interested in how the female psyche evolved.

The narcissistic nature of the culture in the gymnasium and women’s locker room engaged my attention, and I used photos that I took in those environs. That is where the use of the mirror, the doubling of the image, and the presence of the camera in the picture evolved from the mirrored walls of those public spaces. I experimented with more expressionist uses of the paint and color in the representational imagery, and the mirror permitted many liberties.

Discarded mannequins I found on the street became models for another series. That worked for me as a way of critiquing the mass-produced idealized form that fashion and commerce always imposed on us in media and movies. The mannequins had beautiful, painted faces and sometimes missing limbs and empty armholes, creating an almost surreal feeling as they faced the viewers in silent accusation.

I gradually moved back to total self-nude as the paintings, which I had developed and thought of as cultural commentaries, never gained real traction in those years. They were exhibited and written about, but the domination of the art world trends and major players left little room for dissonant voices.

I returned to a more realistic rendering of the self-nude holding the camera in the mirror. It called up the memory of my earlier self-nude works, but now instead of trying to see from my own viewpoint, I viewed from the mirror holding the camera in front of my face, thus incorporating the who’s looking at who dynamic.

I needed to enlarge the image to develop the scale in which the nude becomes a kind of enveloping abstraction.

I also did a series of small paintings which I called “Heads.” I had been often criticized for not showing the woman’s face, so I made about 15 small paintings of my face, each seeming like a different person, and said they were the heads that I had been accused of cutting off.

I gradually returned to self-images in various positions with more abstract colors and developed varied styles of working so that each piece was, in a way, an abstract piece.

Meanwhile, of course, I had been getting older, and the issues of the aging body became self-evident. I was happy to have a new cause.

Which artists or movements have had the most significant impact on your work, and how have your influences changed over time?

Once I returned to NYC, I saw everything that was going on, and I didn’t know that any particular artists were influential to me. It was the tremendous excitement and ferment of the whole art scene that was a turn-on. I was trying to do something that no one else had ever done. If someone had already done something, I had no interest in also trying to do it. The influences are much more subtle and tend to creep into the work without one being aware of it. As a young artist, I was most influenced by the usual culprits of both Modernism and Abstract Expressionism: Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró, and then Willem de Kooning and Philip Guston. As I returned to figuration, Georgia O’Keefe, Alice Neel, Jenny Saville, Lucien Freud, and Paula Rego became influential. The Feminist movement, its goals, and critiques of the system were more influential for me than various artists and art trends of the moment. The content in representational painting seemed to me more important than style, and it was, for that reason, interesting. Multiple elements of different styles were conceivable in one work. Voilà! Postmodernism has arrived.

How did your involvement with the Feminist Art movement and groups like the Guerrilla Girls shape your approach to art and activism?

A male artist once said to me, “You women are lucky, you have a cause!”

Despite the obvious irony behind the remark, in a certain sense, the power of belief in something larger than oneself focuses one’s energy. The time in which I became an adult was one of enormous change and disruption to norms. The sexual revolution was supposedly the doorway to freedom.

However, that struggle is still ongoing, and the structures of state, capital, and religion are vigorously defending their territories.

For women, this revolution is extremely personal. It affects how we fashion our lives and our destinies. The restrictions on our choices are still self-evident. The personal nature of these restrictions belies the political nature of the problems, and so it has taken some time before many have understood the necessity to address change both individually and publicly.

Having lived in Spain for seven years as a foreigner, during the time of Franco and of Vietnam in the US, I understood the role that artists took in resisting the dictatorship and the war. I came back to this country committed to engaging politically.

My first experiences in trying to enter the professional art scene (i.e., the gallery world in NYC) were disheartening. Despite having exhibited widely in Spain and South America, I could not get past the front desk in most galleries in NYC. However, the community of artists was open, and I went to Art Workers Coalition meetings, where I met many other artists. The women at those meetings began to form their own groups as they were tired of being forced into subsidiary positions. Thus I became acquainted with many other women artists and their work and issues. The one thing that was universal across all the factions was the experience of having been refused entry into the mainstream of the art world because of their sex.

This experience taught us to network and support each other regardless of differences, to share job and exhibition opportunities, and to agitate for entry. Although it was helpful for discussions of differences, emotional survival, and the bonding of groups of like-minded people, things changed very little for years.

The slowness of change was a stimulus for the shift to a more proactive strategy.

There were various publications and lobbying groups formed in the 80s. The most well-known and arguably effective were probably Heresies and then later the Guerrilla Girls.

Through a tip from a friend in the network, I landed a teaching job at Douglass College, later to be known as Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, where I taught painting for 22 years as a tenured professor. That provided me with the economic support I needed to be able to take many risks without needing to sell my art. There was also interesting and exciting faculty, from different parts of the spectrum, like Leon Golub, Geoff Hendricks, and Mel Edwards, to name a few. I liked teaching, and the contact with young people allowed me to connect with and support many young women on their way into the art and professional world. It was a perfect “day job” that kept me from being too isolated in my studio and connected me to other realities.

How do you navigate the tension between creating art that represents female sexuality and the risk of it being misinterpreted through a male gaze?

We can’t always control everything. I cannot self-edit so that I won’t be misinterpreted. I have to allow the viewer to bring whatever his or her experience is to the viewing of my work. I have always stated my position. I am sure that at times it has been challenged. Nevertheless, the reaction that I have received from so many, especially young women, in recent years seems to connect with my intentions. At the worst, it will open the conversation.

The ever-present male gaze feels much less potent nowadays. Sexuality, in general, feels somewhat less omnipotent. Perhaps that’s just through my ancient eyes.

Have there been moments when you felt constrained or misrepresented by the label of “feminist artist”? How do you prefer your work to be contextualized?

I have at times felt misrepresented when the label has been used to segregate me from other categories. I would wish to be included in a show about realism, or one on figuration, one on abstraction, one on political art, etc., when those elements are so much a part of my work, and not be confined to only Feminist shows or women artist shows. When Feminist Art is acceptable as part of mainstream art and enters the canon as such, I shall be content to be categorized that way. I think we need to be moved from the footnotes of history and into the mainstream.

Reflecting on your career, do you think the art world has made substantial progress toward gender equality since the 1970s? Where do you see the most room for improvement?

When I left abstraction, I did so because I could no longer connect with what art had become in those years: Pop Art, Color Field, Conceptualism, Minimalism. I wanted something more personal, and I wanted my art to also connect to my feminism. The question was how to do so without making it a propagandistic tool rather than a work of art.

I do think some progress has been made in allowing women to enter the system and to value our work, but only because of the pressure being brought to bear for women to be able to enter, politics and business, etc. The test will come when the next big movement materializes and is promoted. Will it be white male again, or a kind of identity group manifestation, or truly multicultural and multi-sexual? Perhaps the idea of the universal is outdated, and all we can do is go back to our own corners and then come out and dance instead of fighting.

What are your thoughts on the current state of the art world, particularly concerning the representation of women and other marginalized groups?

I prefer not to comment on the art world, which we cannot live without, nor can we find our way within. Hopefully, things are somewhat better now for women and other groups, but like in the larger world, the manipulators are always busy.

How do you maintain your artistic integrity in an increasingly commercialized and market-driven art world?

I have been very lucky to work with a gallery, Alexander Gray, who is committed and ethical, and he has been a great and consistent guide who I trust.

How do you see the relationship between art and societal change? Has your work responded to specific cultural or political events?

My work has represented how I, as a person who is connected to the world, have absorbed the issues of my time and how I have attempted to respond to change the way we see and are seen. I don’t think my work responds to specific events. Teaching has been important in keeping me aware of the changing landscape.

How has your personal life, including your experiences as a mother and survivor of illness, influenced your art?

A person’s confidence, stubbornness, and resilience will affect how she will function as an artist. For me, breaking with the expected roles that I was supposed to fill was very important in taking the next step by finding my own voice in the work.

What have been some of the greatest challenges you’ve faced as an artist, and how have you overcome them?

I had to learn to develop more skills as a realist. I had always been taught in school to flatten, simplify, and distort, but the camera brought sufficient distortions. By teaching myself how to see very closely, inch by inch, the slightest variation in an edge or color could totally change the form, and so I gradually became known as a realist painter, the most unfashionable designation possible.

Once I had that down and produced several series in that mode, I reverted to using more than one style in the work. How to retain the immediacy of the impulse and the integrity of the form was a worthy challenge. The paintings in my last two shows reveal the results of taking on that challenge.

Your work is known for its vivid use of color and form. How do you approach these elements in your paintings, and what do they signify for you?

Color and form are the basic building blocks of all of my work. It is there that the work begins, and how it develops and surprises is essential to the success of any piece.

How have your techniques and use of materials changed over the years? Are there any new mediums or methods you are currently exploring?

I have always loved oil paint and have continued to use it throughout my career. I have not been very interested in experimenting with new methods or materials. From time to time, I engage in collage and drawing, usually with oil pastels which are almost like oil paint.

What do you hope your legacy will be, and how do you hope to influence future generations of artists?

I am always surprised when young people today tell me how important my work has been to them. I thought that surely the issues that have absorbed me would no longer be relevant for them. Perhaps just revealing the problems and leaving the solutions open gives the work longevity. If the work has resonance, it will endure. I am happy to know that my work has meaning for others, but the world is in such a precarious position that one simply hopes for survival in general terms.

The concept of future influence and legacy feels a bit like a futile conceit.

What advice would you give to emerging artists, particularly women, who are trying to find their voice and navigate the art world today?

There are many different ways of becoming, and we each have to invent our own. It is, however, necessary to know that it is a long road with ups and downs along the way. Persistence and self-confidence are vital, as well as good friends, people outside of yourself to care about, and some way of achieving minimal economic stability. Its rewards are a life that is interesting and sometimes exciting. The art world today is much larger than it used to be. I never learned how to navigate it; someone just threw me a lifeline, and I held on tight.

All images courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates

Editor: Kristen Evangelista