By Carol Real

Helmut Ditsch, an artist caught between grandiosity and obsession, has built a career that defies the logic of the contemporary art market. His paintings, monumental in scale and ambition, occupy an uncomfortable territory between extreme realism and sensory experience. For Ditsch, nature is not a landscape to be observed from a distance but a territory to be physically conquered before being transferred to the canvas.

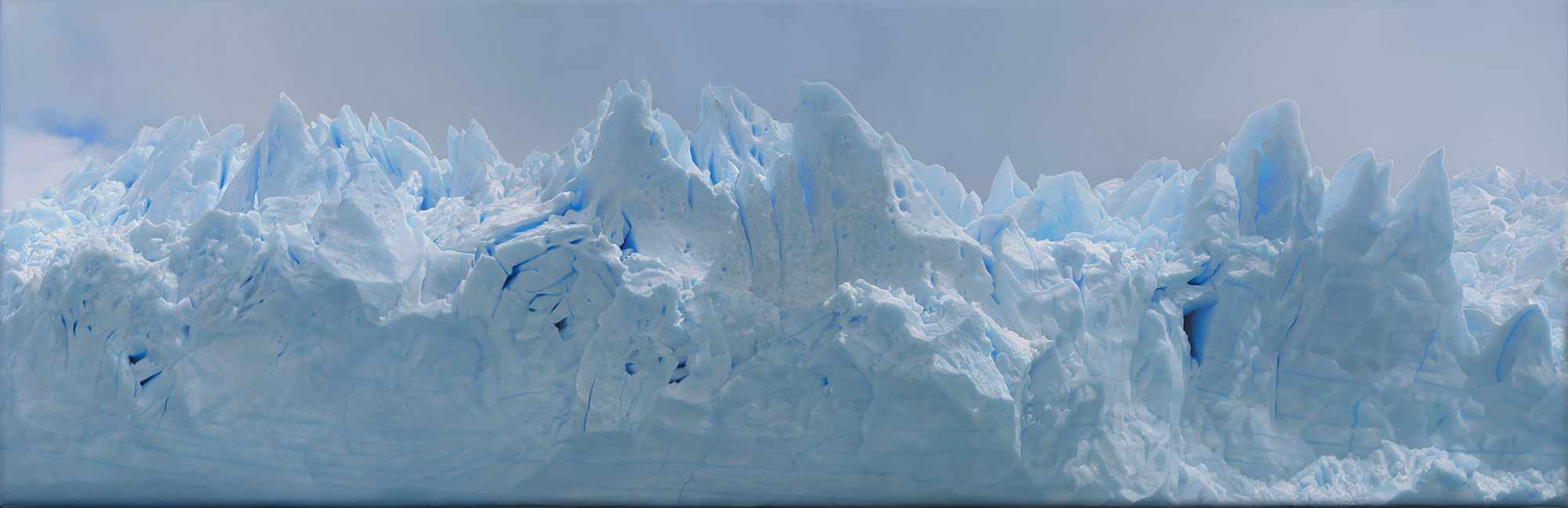

From his early days at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna to his record-breaking sales in the international market, his trajectory is that of an artist who never fit within institutional art structures. His works, inspired by glaciers, deserts, and oceans, are a testament to his devotion to the sublime. Rather than merely observing his subjects, Ditsch immerses himself in them: climbing mountains, traversing vast expanses of ice and water, and translating those experiences into canvases saturated with detail, with a meticulousness bordering on obsession.

His most recent sale, a piece inspired by the Perito Moreno glacier acquired for 1.6 million euros by the HPH Privatstiftung, cements his position as the most highly valued Argentine artist. However, despite his commercial success, his work remains in limbo between popular reverence and skepticism from the traditional art circuit. His paintings, which may evoke the solemnity of Caspar David Friedrich, are rarely seen in institutions such as MALBA or at fairs like arteBA. Instead, his work finds an audience in private collectors and patrons inclined toward the epic and the grand.

Ditsch does not only paint but also composes music, designs automobiles, and, more recently, has ventured into filmmaking. His first movie, still in progress, is a tribute to his mother and deceased wife, central figures in his personal mythology. This expansion of his practice reinforces his vision of a total art, in which painting, music, and philosophy intertwine in a mystical quest.

His view of art as an independent enterprise has led him to reject the gallery system and opt for a self-management model that, while ensuring absolute control over his production, has also kept him on the margins of certain curatorial narratives. “The art market is a dogmatic system,” he has stated in interviews. “I prefer a direct relationship with my patrons, like in the Renaissance.”

The risk of his approach is evident: his work, hailed by some as a new Romanticism and by others as an anomaly in the contemporary art landscape, exists in a space where grandiosity can verge on kitsch. There is no irony in his work, no nods to conceptual art. His proposal is direct, emotional, and monumental. And perhaps for this reason, in an era dominated by postmodern art and digital speculation, Ditsch’s insistence on painting as a heroic act is, in itself, a challenge to the rules of the game.