Last week, I had the honor of visiting Fred Tomaselli’s studio. He warmly welcomed Art Summit into his creative haven, where the realms of artistry and innovation seamlessly merge.

Upon entering his studio, I immediately noticed that, although there were only a few artworks on display, each one radiated exceptional quality, capturing my attention instantly. His older yet highly esteemed pieces harmoniously coexisted with his latest works in progress.

In one corner of the second room, a drawing hinted at an exciting project cloaked in secrecy for the time being. Fred Tomaselli has embarked on an extraordinary venture, a significant addition to New York City’s bustling transportation system. While the specifics remain confidential, it promises to become a highly impactful and widely recognized public masterpiece.

Fred graciously invited me to join him for a cup of tea as our conversation began, but not before he took a moment to introduce me to the intricate world of his resin work, highlighting the meticulous craftsmanship that defines his artistry.

Nestled in the heart of the East Village, Fred Tomaselli’s studio resides within a building rich in its own historical significance. He mentioned that renowned artists like Yayoi Kusama and other big names have also left their creative legacies within these walls.

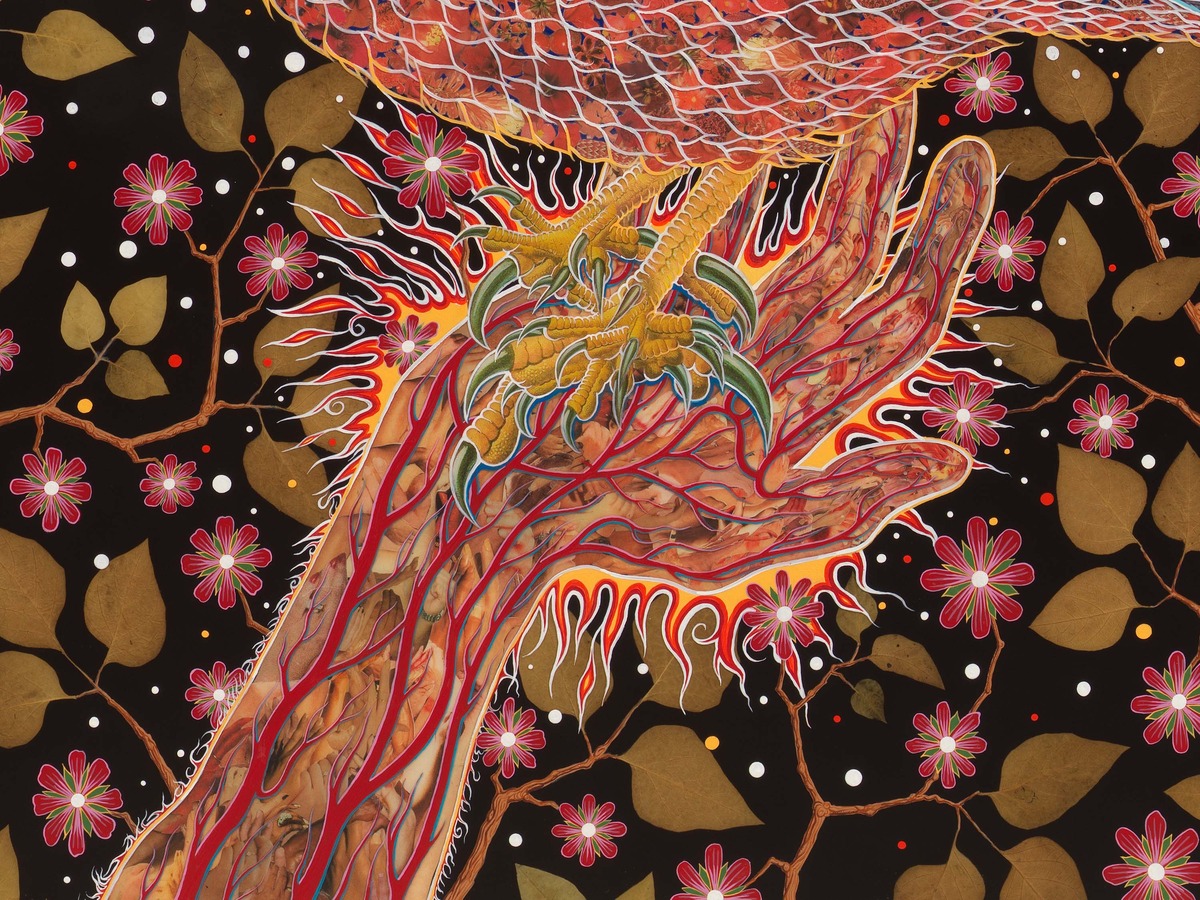

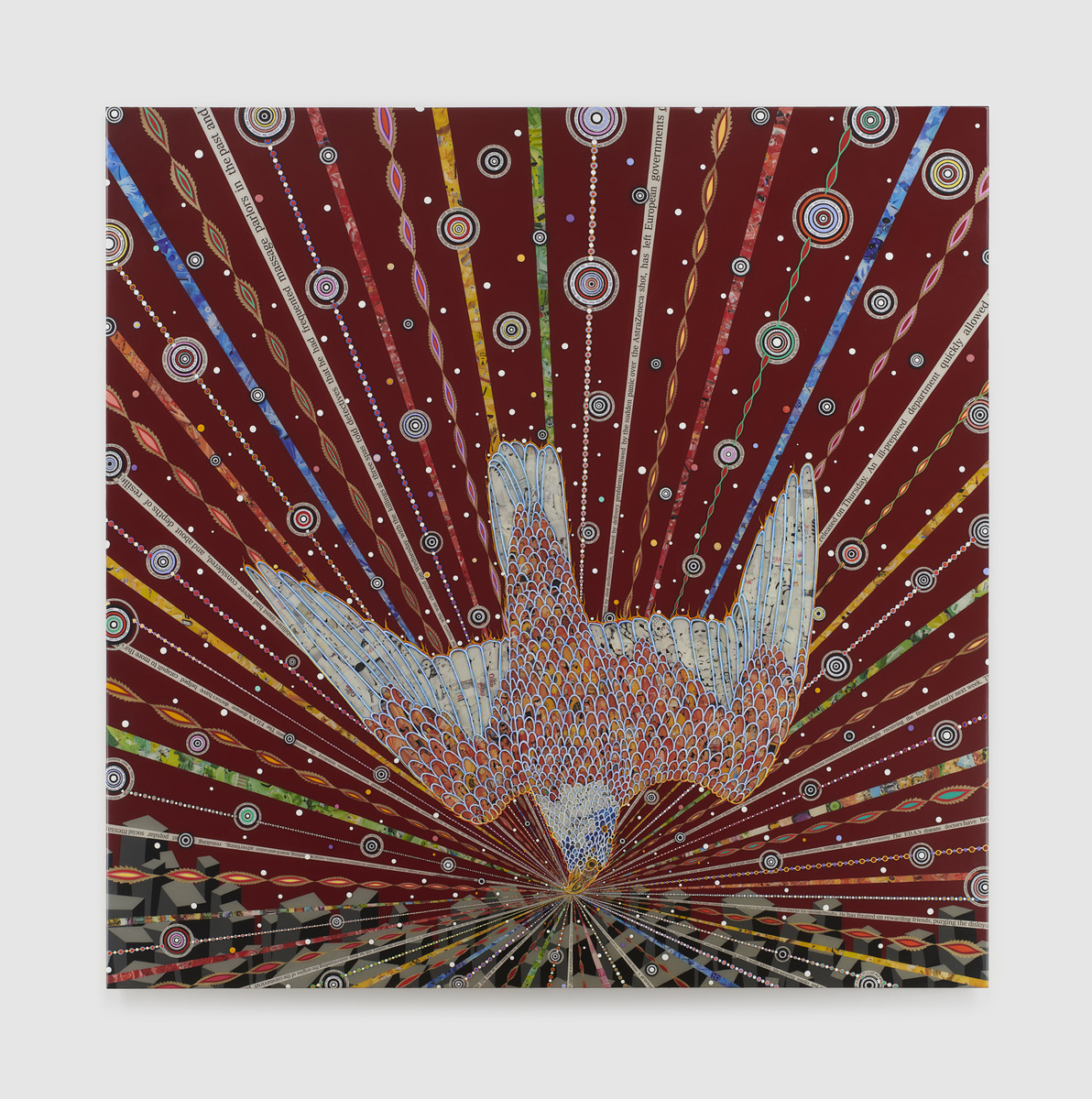

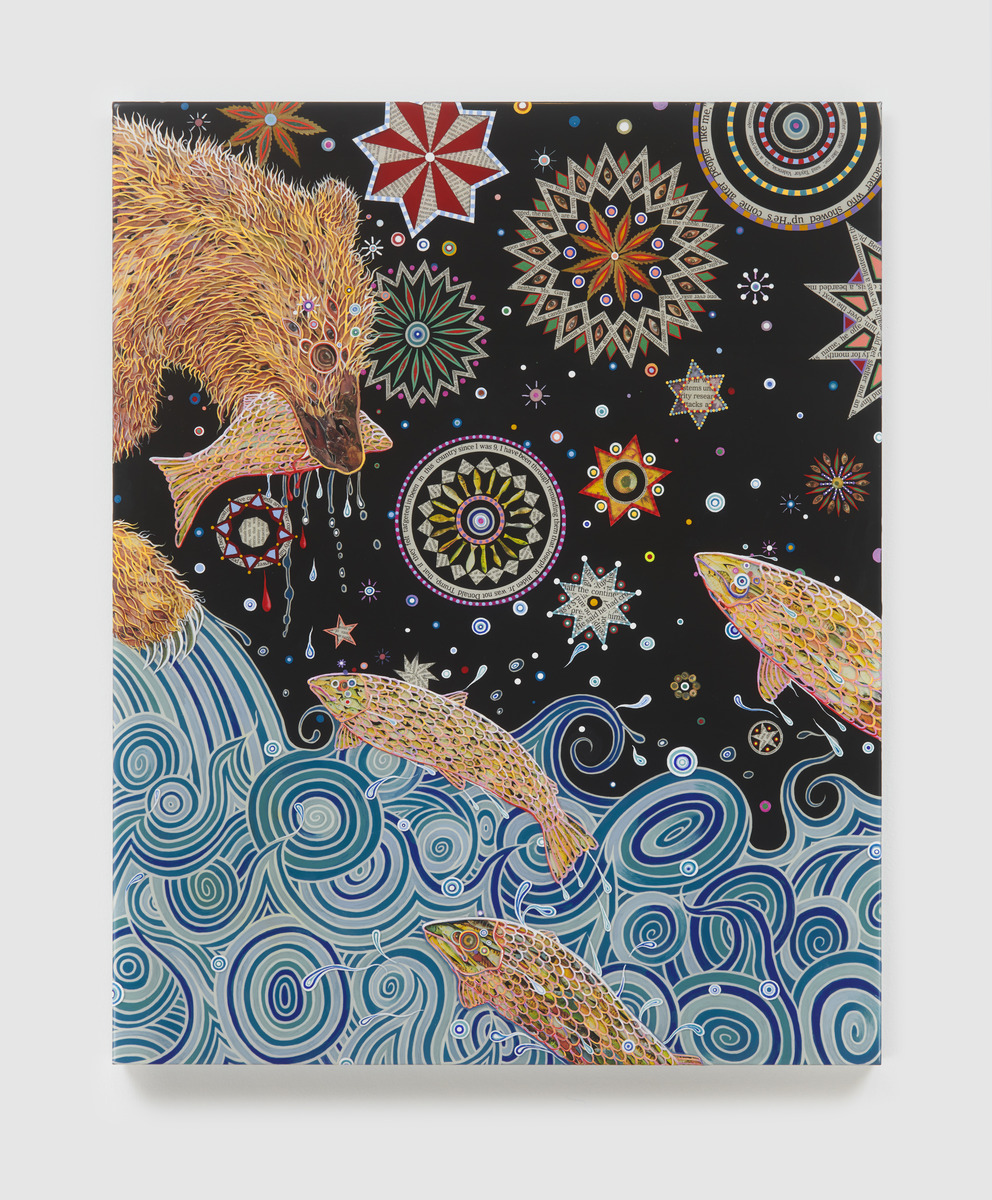

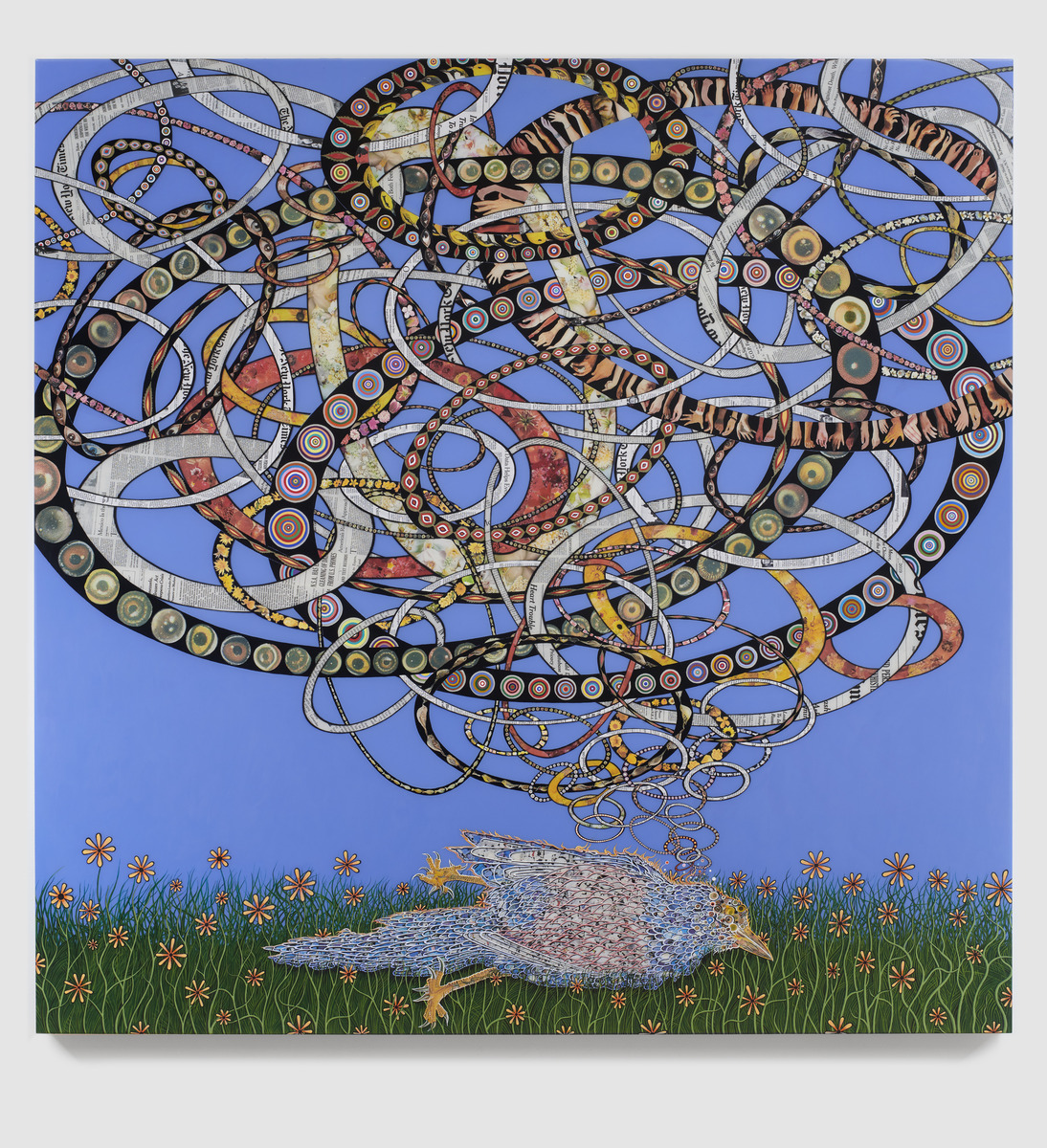

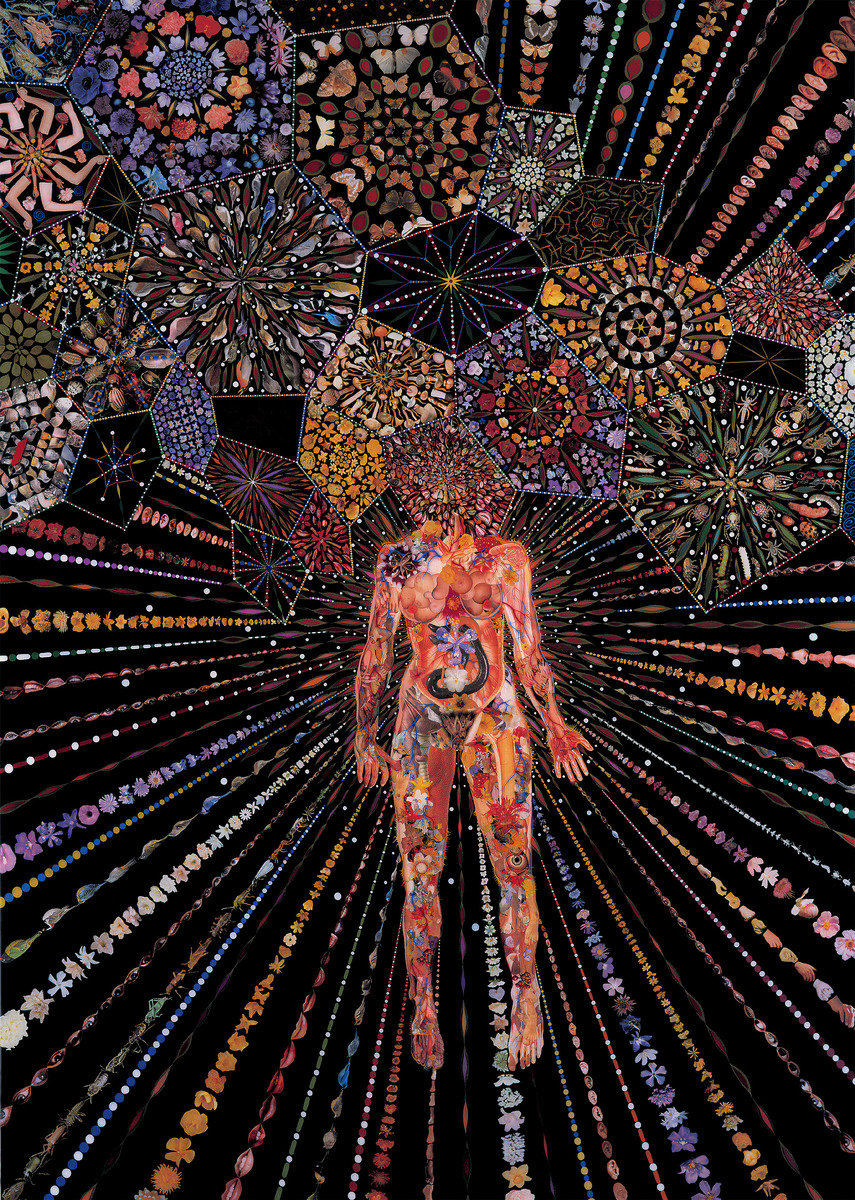

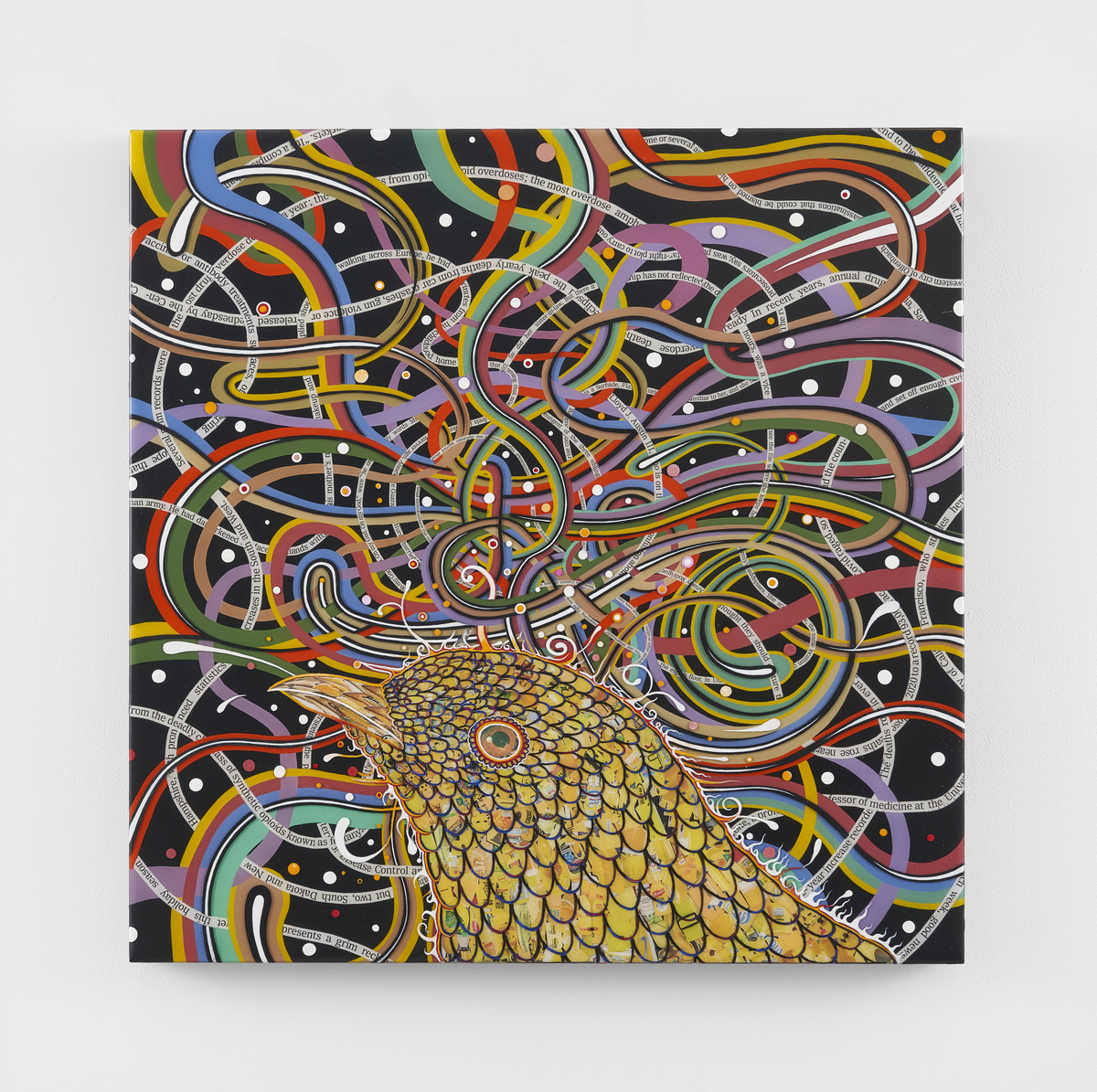

Fred Tomaselli, a gifted artist born in Santa Monica, California, in 1956, is a highly acclaimed American artist known for his exceptional and captivating artworks. His creations transcend conventional boundaries, blending a diverse array of materials and imagery suspended within thick layers of clear epoxy resin. These meticulously crafted pieces on wood panels are truly mesmerizing, drawing viewers into intricate patterns that appear to organically sprawl across the canvas.

Tomaselli’s artistic journey draws inspiration from a wide range of sources, including art history, Eastern and Western decorative traditions, and the realm of hallucinogenic experiences. His signature works are enigmatic hybrids that blur the lines between paintings, tapestries, quilts, and mosaics. They are composed of a remarkable array of elements, including over-the-counter and controlled pharmaceuticals, street drugs, natural psychotropic substances, organic matter, collaged elements from printed sources, and hand-painted ornamentation. All these components harmoniously coexist within glistening layers of clear, polished, hard resin.

In his artworks, forms seem to oscillate, explode, implode, buzz, loop, swirl, and spiral, creating a visual symphony that defies easy categorization. Actual objects, photographic representations, and painted surfaces exist without hierarchy, giving rise to an electrifying and destabilizing experience. Tomaselli’s art neither fully embraces reality nor wholly indulges in illusion; instead, it strikes a unique balance that leaves viewers captivated and disoriented in equal measure.

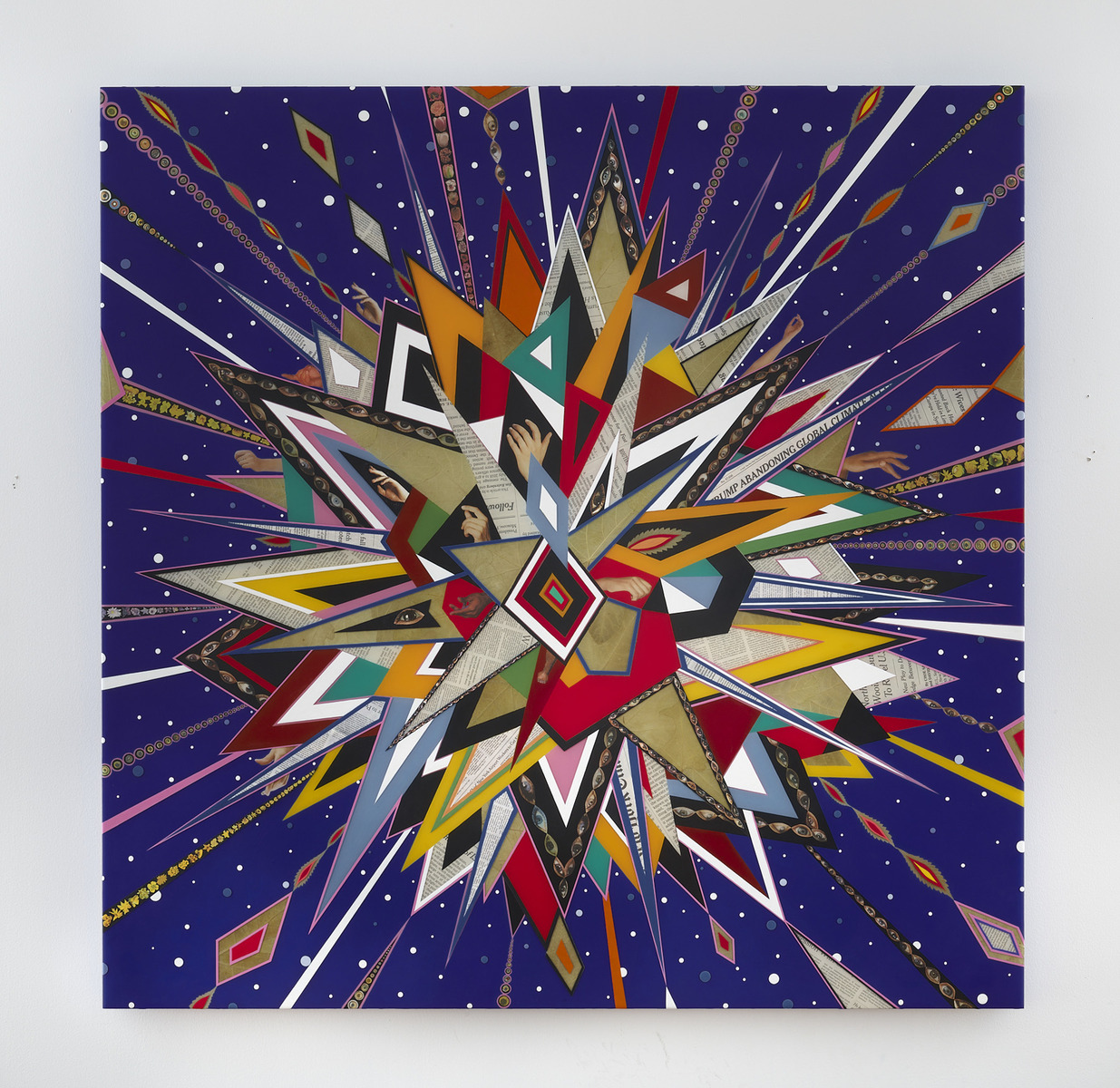

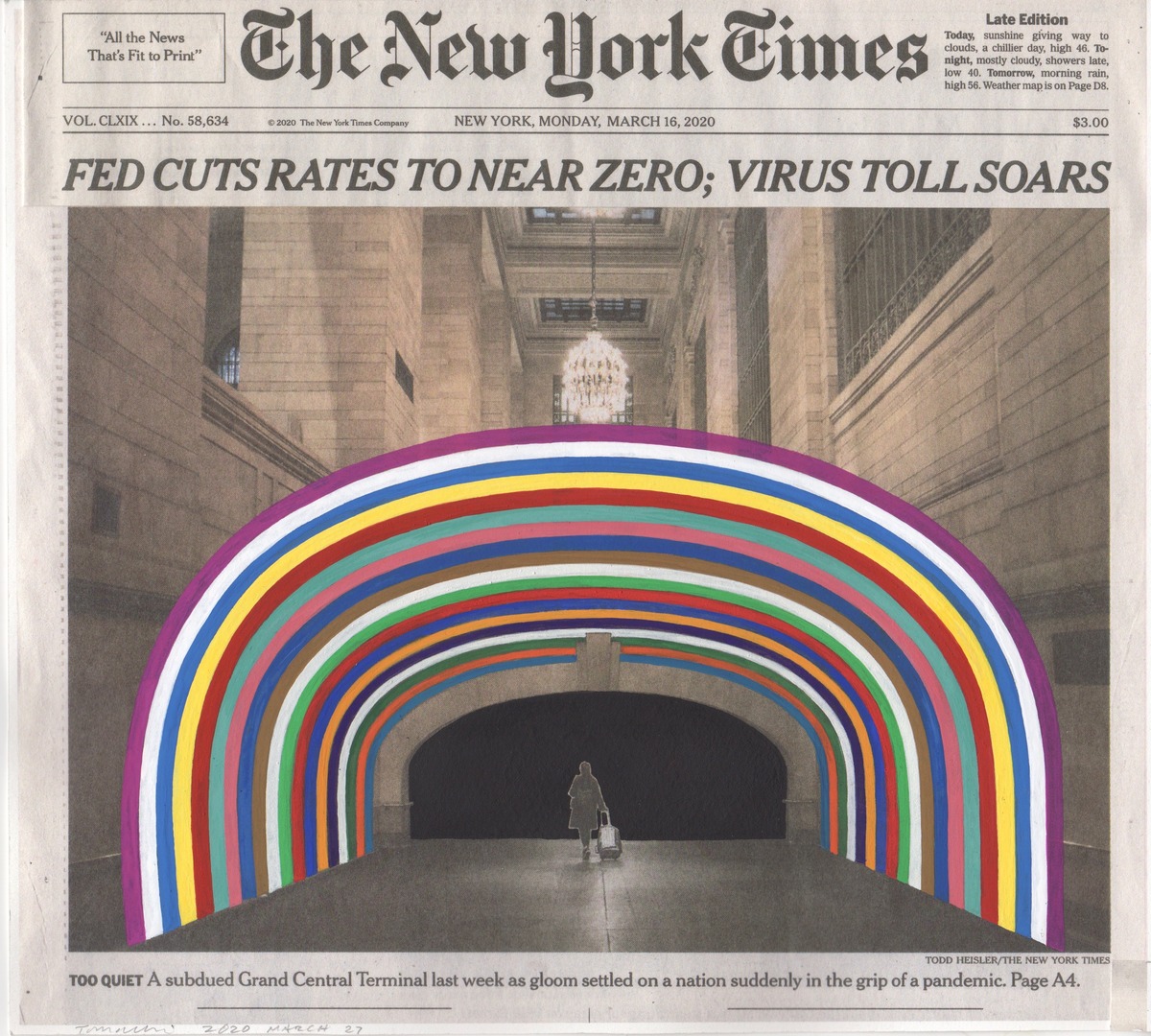

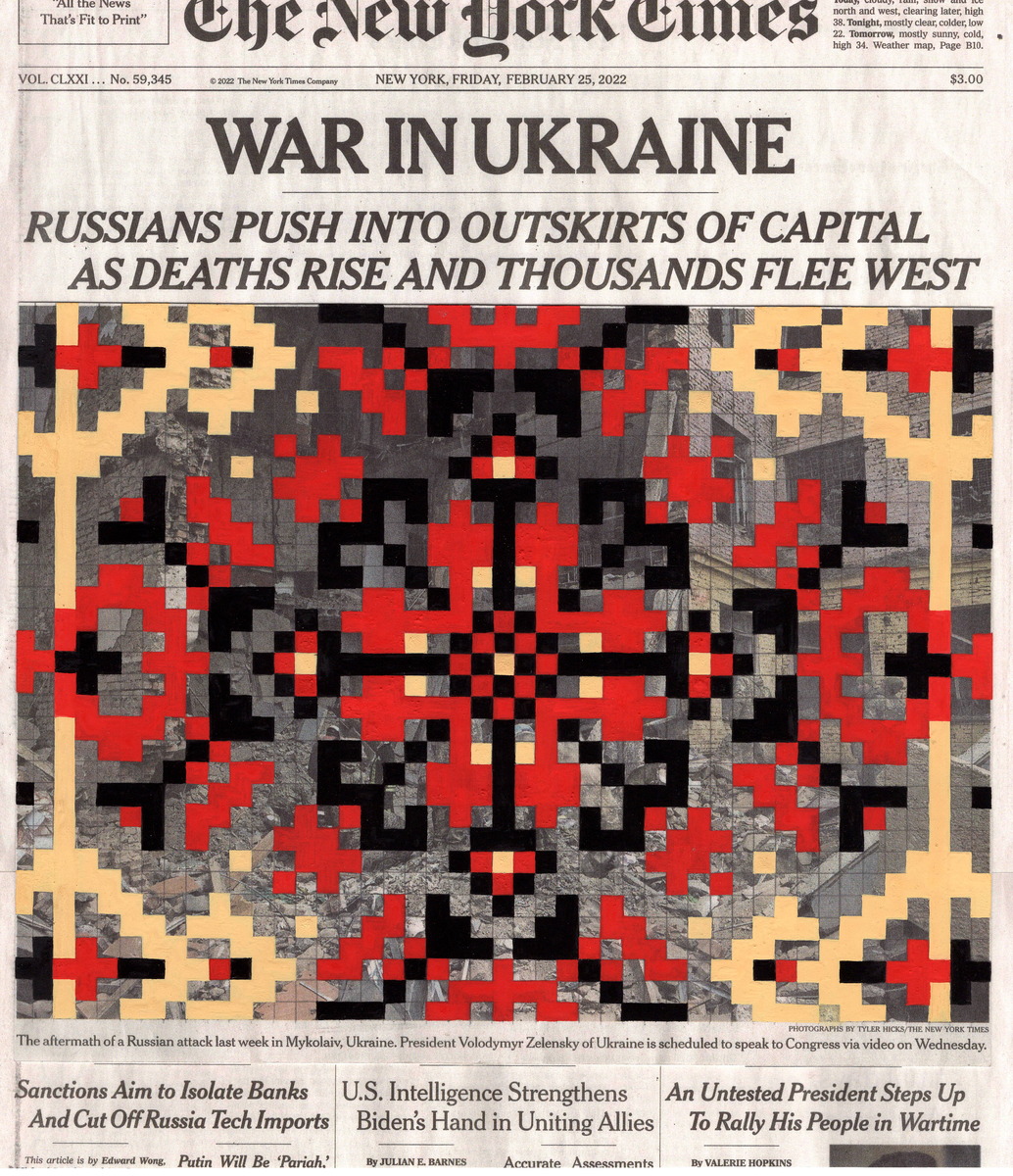

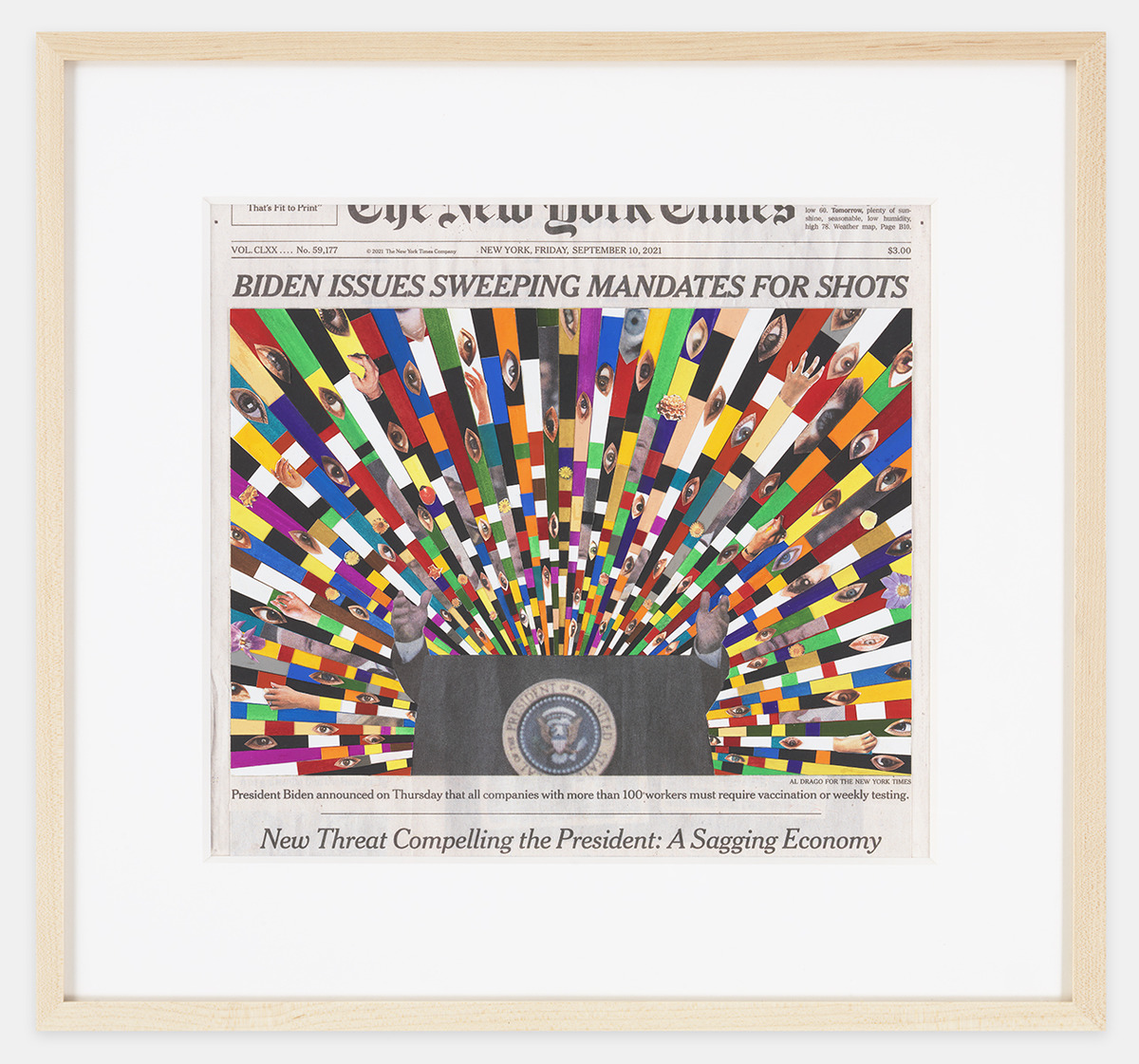

In 2005, Tomaselli embarked on a new artistic journey, creating a series of works on paper that transformed the front page of The New York Times. Using gouache and collage, he reinterprets these news headlines, offering a surrealist perspective on the absurdity of news cycles. His creations serve as a canvas for responding to a myriad of issues, from regional anecdotes to global crises. In his own words, these Times collages may be “quietly political,” providing him with a platform to riff on diverse subjects while the chaos of the world serves as the backdrop. It’s his way of saying that despite the world’s troubles, he continues to create and paint.

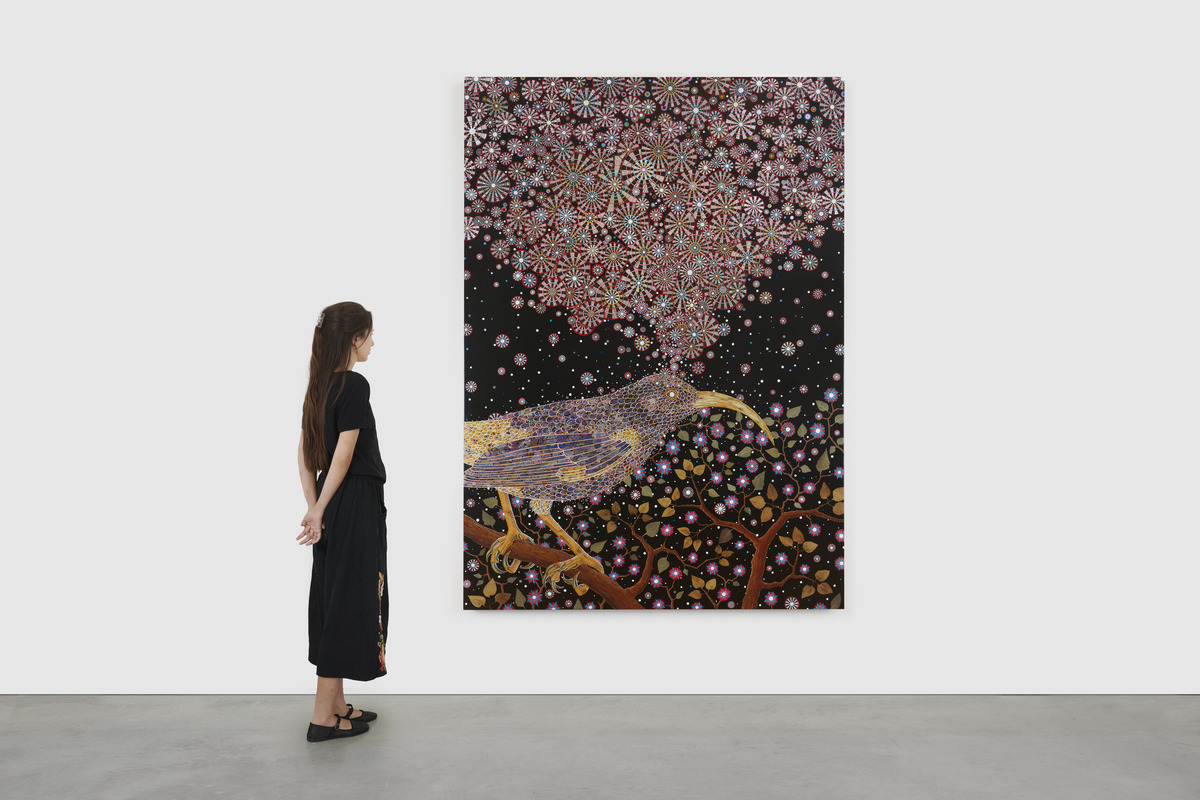

Fred Tomaselli’s artistic influence extends far and wide, with solo exhibitions at prestigious institutions such as the Joslyn Art Museum, Oceanside Museum of Art, Toledo Museum of Art, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and the University of Michigan Museum of Art, among others. His works have been featured in international biennial exhibitions and are held in esteemed public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and many more.

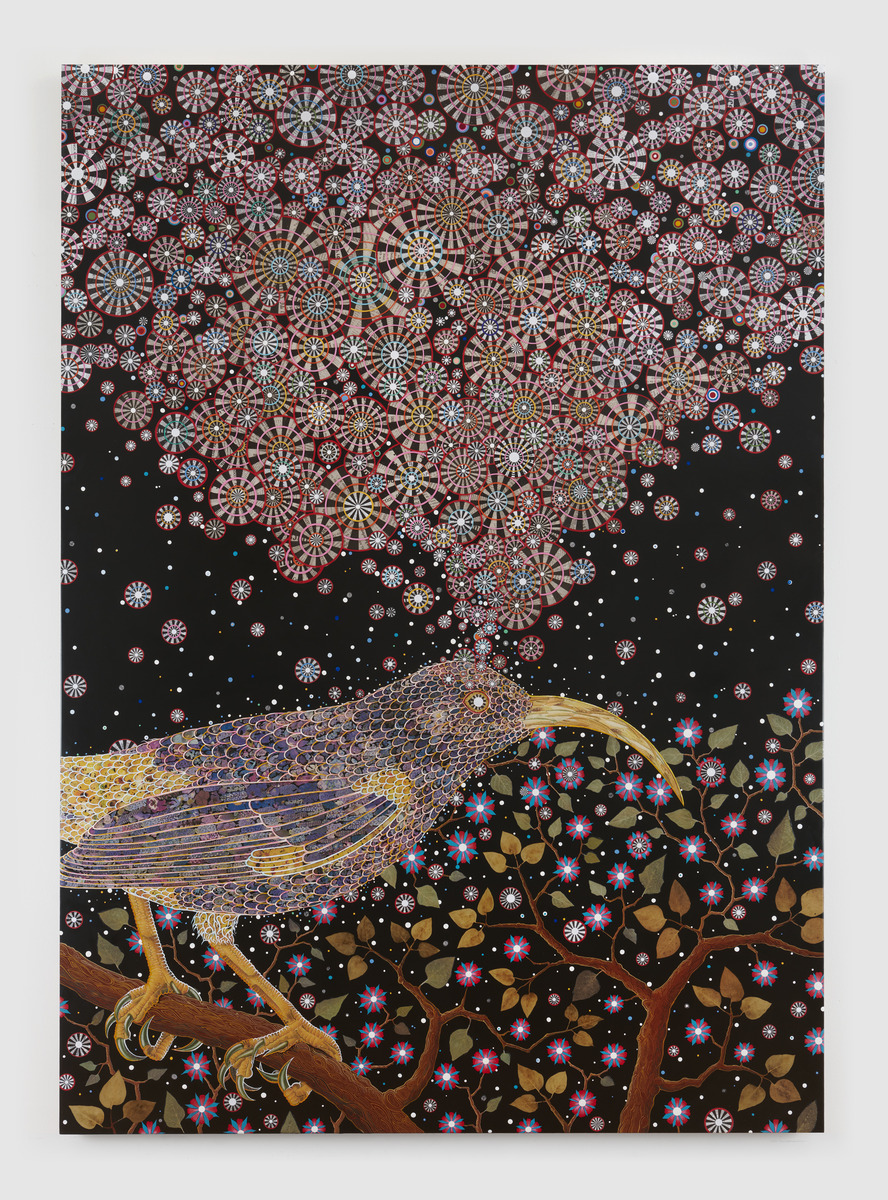

His distinctive artistic language, blending intricate details, hallucinogenic influences, and a touch of the surreal, transcends traditional boundaries. His creations invite viewers to immerse themselves within the intricate tapestry of his imagination, offering a seductive and transportive experience while revealing the inner workings of artistic allure. With each piece, he beckons us to escape into his world, unburdened by radical agendas, and immersed in the pure essence of artistic expression. Fred Tomaselli’s work is a testament to his passion for nature, gardening, bird-watching, and the unapologetic pursuit of his artistic vision, encapsulating the artist’s unique perspective on reality.

In addition to his artistic achievements, Fred Tomaselli, born in 1956 in Santa Monica, CA, has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions including the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE (2019); Oceanside Museum of Art, Oceanside, CA (2018); Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH (2016); Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (2014) and the University of Michigan Museum of Art (2014). He has also presented a survey exhibition at Aspen Art Museum (2009) that toured to Tang Museum in Saratoga, NY, and the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn NY (2010). His works have been included in international biennial exhibitions, including Sydney (2010); Prospect 1 (2008); Site Santa Fe (2004); Whitney (2004), and others. Tomaselli’s work can be found in the public collections of institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art; Whitney Museum of American Art; Metropolitan Museum of Art; Brooklyn Museum; Albright-Knox Art Gallery; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Orange County Museum of Art, Santa Ana, CA; and many others.

An Interview with Fred Tomaselli

By Carol Real

Your artwork combines a wide range of elements and materials, including prescriptions, pills, botanical illustrations, and more. Could you please explain the symbolism and significance behind these choices?

Back in the eighties, I was contemplating some of the rhetoric surrounding pre-modernist art and the idea of paintings as windows to other realities. When one enters this metaphorical window into the world of the painting, it might intersect with ideas of transcendence and the sublime. I found that this rhetoric bore a striking resemblance to the discourse around psychedelic drugs, which had influenced me but was a suppressed subject in the art world at that time.

I thought that the concept of art as a means of transportation to other dimensions felt very much like the perceptual-altering experience of hallucinogens. Consequently, I decided to incorporate pharmaceuticals and botanicals into the paintings so that they could be used as vehicles for altering perception. Instead of affecting consciousness through the bloodstream, they would travel through the eyeball. This represented a different route to altering perception, and perception is what artists are primarily interested in.

Over time, in the additive processes of my work, I began adding collage elements and eventually paint. One aspect I appreciated about the direction the work eventually took was the combination of the real (such as plant material and pills) with photographic and painterly elements. At times, it was challenging to distinguish between the three. For me, this blurring of reality was also an essential part of the message I was contemplating: How do paintings function? What do they do to our brains and perceptions? How does this factor into history? What is society’s relationship to reality?

Your artistic creations have been characterized as a fusion of surrealism and reality. How do you manage to harmonize these two aspects in your artwork?

I’m a bit torn about the term “surrealism” because it means different things to different people. Anyway, a lot of my work starts with something real, for example, maybe a photograph of a recently declared extinct bird, a bird I’ll never see. Then, I embellish that bird into something else, which is where surrealism might come into play. My aim is to elevate the real into something magical and intense.

Regarding my creative process, I usually have a rough idea of what I want to do, but I allow for a lot of improvisation along the way. It might start with a sketch or a general notion of where I’m headed, but the details often evolve while I work. I change my mind, adjust, and follow intuitive impulses, like any painter.

For example, some years ago, I was primarily working with geometric-based abstraction. I was creating a painting based on the chemical analogs of psychotropic drugs, mostly related to psilocybin and LSD molecules. Halfway through, it started to resemble a cloud, reminiscent of the toxic airborne event described in a novel I was reading at the time, Don Delillo’s White Noise. This led to thoughts of alien abduction and the ascension of Mary into heaven. Then, this prompted me to cobble together a woman being drawn into a sky of chemical clouds.

The use of epoxy resin to encase your artworks is a distinctive technique. What advantages and challenges does this medium present for your creative expression?

I grew up in Southern California, where some of my friends were surfboard shapers. Consequently, I began working with resin when I was a preteen, helping shape surfboards in garages. At that time, we used polyester resin and fiberglass.

When I started pursuing art, I wanted to preserve water-soluble and ephemeral materials by encasing them, much like bugs preserved in amber. I thought, “What if I could do the same with psychoactive drugs and plant materials?” I could encase these objects in a tamper-proof material for eternity, mostly unchanged. Over time, the colors of leaves might shift, but their essence remains intact. Additionally, I’m drawn to the surface quality of resin. In many cases, I consider these art pieces as vehicles that can transport you to other destinations, much like cars or surfboards. They share a similar shiny and seductive quality, and I’m deeply interested in the mechanics of seduction. It’s a reminder that we are all seduced to alter our perceptions, and it’s an inherent aspect of being human. Neurobiologists discuss the fifth drive, the urge to alter consciousness, which follows basic needs like eating, drinking, sex, and sleeping. This drive to alter our perception has been fundamental to humans throughout history. There’s speculation that religion may have emerged from the use of entheogenic substances like mushrooms or ayahuasca, leading to the invention of God. So, the seduction to alter one’s perception is deeply ingrained in our humanity, and I wanted to explore that concept in my work.

Your art has been described as thought-provoking. What kind of questions or discussions do you aspire to elicit among viewers and critics?

Well, first of all, I think that the ambiguity of an artwork gives it strength. So, I don’t want to over-explain what anyone else should take from my work. Everyone’s entitled to either experience it in a superficial way or a deep way, that’s up to them. That being said, I have my own ideas, and partly, it’s what I was talking about earlier–the exploration of altered perception and consciousness and its relationship to art and art history.

But I’ve also explored utopianism and its discontents. For example, in the late 90s, I made a series of works that dealt with utopian communities in North America that were either religious or politically-based. I was interested in the factionalization of these various ideologies and how America imposed ideologies onto nature, specifically the doctrine of manifest destiny that involved the enslavement of people and the killing of Native Americans in the name of God. So, this has been a history, a legacy of American utopianism that we all wrestle with; we’re all on blood-soaked, stolen land.

This social history also finds a rhyme in my personal life and in art history. For instance, I grew up in the 70s when hippie utopianism was burning out into disco and cocaine right around the time when art was moving from modernism to postmodernism. So, there was this simultaneous collapse of faith both in hippie idealism and modernism, which sent me wandering through the rubble of recent utopian failure.

If you look through the rubble of art history, you’ll notice utopic moments that have collapsed. You’ll see the Italian Futurists collapsing into fascism, and the Russian Supremacists becoming Stalinists. You witness these moments of intense hopefulness and idealism come crashing and burning. That’s part of what’s baked into what I do as an artist.

The use of psychoactive plants and imagery in your work is intriguing. How do altered states of consciousness or spirituality influence your creative process?

I’m a secular cosmic enthusiast. I don’t necessarily believe in God in the traditional sense of a deity, but I do believe in a higher consciousness that encompasses the sum total of the universe. It’s something awe-inspiring and too vast to fully comprehend. My goal is to infuse that sense of awe and the sublime into my work without requiring anyone to believe in a specific God. I find the universe and the world to be incredible, and that’s where my inspiration stems from. I draw my inspiration from the wonder of science, the amazing diversity of animals and plants in the world, and the beauty of the stars in the sky.

Your resin works involve meticulous layering and arrangement. How do you maintain a balance of precision and spontaneity in your creative process?

It might surprise some people, but while there are a lot of meticulous processes at work, there’s also a significant element of spontaneity, and I do improvise as I go along. It may appear like I have everything planned, but the truth is, I’m making things up as I proceed.

Can you share any specific experiences or moments that have had a profound impact on your artistic vision and style?

When I was a teenager, I remember visiting a dimly lit gallery with what appeared to be a black rectangle painted on the wall. My friends and I initially thought it was ridiculous. We laughed at it, and being a naive kid, I touched the piece. To my surprise, my hand went into what seemed like limitless space. I thought, “Oh, wow!” It turned out to be an early work by James Turrell. That experience taught me that what you see isn’t necessarily what’s there; you need to look again. It felt like magic to me because Turrrell created the illusion of a solid flat object on the wall that was, in fact, an empty, limitless void. This was a little different from artists like Donald Judd, who famously said, “What you see is what you see.” James Turrell and other Light and Space artists made me realize that what you see can be deceptive, and there’s more beneath the surface.

Another influential experience was seeing Bruce Nauman’s retrospective in the early 70s at LACMA in Los Angeles. Until that point, I had a narrow view of art, thinking it was limited to artists like Michelangelo and Salvador Dali. However, at that exhibition, I encountered video works, neon installations, closed-up quarters, audio recordings, and they completely blew my mind. It expanded my understanding of art to be anything you wanted it to be. These two experiences were instrumental in shaping my artistic perspective.

Robert Irwin is often considered one of the pioneers of California Light and Space art and one of the most significant West Coast artists. In fact, I recently created a piece as an homage to his garden in LA, which is currently on display at the James Cohan Gallery. It’s called Irwin’s Garden. Ken Price’s wildly finished surfaces also quietly influenced my own. So, these West Coast artists had a profound impact on me as they were the first artists I experienced in a physical space, rather than just through magazines.

Did you always know that you wanted to be an artist?

Well, the theory was that I was a good artist because I could draw well. However back then, I was ignorant of what it meant to be an artist. Coming from a working-class background, I initially started as an illustration major but gradually became more interested in the ideas and wildness of contemporary art. I became increasingly drawn to that direction, and that’s where I stayed.

Were your parents supportive of your decision to become an artist? Parents typically want their children to pursue a more traditional career path, fearing that being an artist may not provide a stable income.

My parents went through financial struggles while raising six kids as immigrants in the United States, so my father was focused on stability. To him, the idea of me becoming an artist felt like a step down in terms of financial security. When I decided to major in art, my father sat me down and bluntly told me that I didn’t have enough talent and that pursuing art would lead to failure. I basically responded with defiance, and despite his discouragement, I persevered. Eventually, both my parents became proud of me. Sometimes, parents can be harsh, but they meant well, and I don’t hold it against them.

Your solo exhibitions have taken place in numerous museums and galleries. How does the physical setting of an exhibition space influence the presentation and reception of your art?

We live in a sea of endless digital imagery. As you mentioned earlier, we’ve become accustomed to viewing almost everything on screens, and we often assume that we’ve truly seen something if we’ve seen it there. A piece of art is much more than that; it is a repository of time that can represent months of dedication. One needs to be in the presence of the object in order to appreciate its scale, tactility, and surface quality. It is a unique experience that cannot be replicated on a screen. In many ways, this makes the singularity of an artwork even more powerful. In my opinion, singular artworks have gained increased significance in this age of constant digital imagery. Simply slowing down, entering a gallery, and immersing yourself in art is an experience that cannot be replicated. I aim to incorporate some elements that cannot be translated into the digital realm. This is why you see layers and shadow play and movement between the surface and what lies beneath. This can only be fully experienced in person.

The New York Times has been a source of inspiration for some of your work. Can we discuss your relationship with the media and how it informs your artistic commentary?

To go back a bit, the drugs, plants, botanical illustrations, and birds in my work often came from things I had lying around my house. I’m an avid nature enthusiast. I spend time with field guides, trying to identify birds and plants. I have a garden in Brooklyn where I grow many of the plants that end up in my artwork. Drugs were once a big part of my life, so I didn’t have to look far for materials. The New York Times is somewhat similar. There’s a new one every morning.

Around 2005, I started working over The New York Times. The New York Times, like all newspapers, is a collective entity with fact-checkers, writers, and photographers all coming together to focus on specific aspects of the world. I decided to become a part of this collective and insert my own editorial commentary into the paper of record. My commentary often adds a cosmic language or a sense of the absurd to the otherwise mundane news. I play around with the context of the photographs and the text surrounding them. In the modernist tradition, there’s often this image of the artist as a rugged individual like a libertarian cowboy. I’m more interested in the concept of collectivity, of working within society to find common languages and ideas. After all, in my resin paintings, I’m constantly pulling images from various authors and photographers, creating a body of work that reflects its collective origins.

What this has done is it’s made me more attuned to how media warps our minds, especially during significant events like the Trump presidency and the COVID-19 pandemic. I consume news on my phone, through the radio, and in print, and I started to realize that the world was sending all kinds of chaotic information into my studio. Despite creating artwork that focuses on joy, beauty, jokes, and the awesomeness of nature, I couldn’t ignore the disturbing events happening around me. I saw it as a reflection of life itself, the coexistence of beauty and chaos.

However I stopped making them for a couple of years prior to 2020 because the constant stream of depressing news was becoming overwhelming. Then, the pandemic brought me back to it. During the early months of COVID, when everyone had to shelter in place, I found myself back at home. I set up a small workspace in a tiny bedroom and started working with the news. Every day brought new, almost unbelievable developments that I couldn’t ignore. It was a way to escape from the world through the making of art, while simultaneously diving deep into its horrors. I couldn’t help but oscillate between these two states. My inspiration for this approach may have come from the constellation drawings by Joan Miró during World War II. He created cosmic, abstract art while Europe was in chaos, but his work didn’t depict the calamity of the world. Instead, he emphasized a cosmic order and the enduring importance of art to human civilization. I felt a similar sentiment and took it as an inspiration.

I haven’t really made any NY Times pieces since the war in Ukraine started. I guess I just needed another break, which led to a shift in my work. Now, my recent resin pieces incorporate elements of the media’s buzz, incorporating phrases and language cut out and recontextualized like a form of concrete poetry. It’s a way to capture the cacophony of opinions and conflicting positions that define our current era. I wanted to explore the duality of nature and the media and play with the tensions between them, reflecting the frictions that exist in my own life.

Do you have any favorite parts of The New York Times or any favorite columns or writers?

I particularly admire Frank Bruni and Michelle Goldberg; they are both super smart. Also, I read the art columns. However, I primarily focus on whatever’s on the front page.

What role did language initially play in your approach to art, and how did your relationship with language change as you navigated a crisis of faith in art and ultimately found your way back to creating art in a more intuitive manner?

I got very excited about conceptual art when I was in art school. I was really taken by Sol Lewitt’s “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”–the idea that art’s primary engine was in the mind. Now, the thing is, I got to a point where I almost talked myself out of making art. It felt like an unredeemable bourgeois commodity that had played itself out and couldn’t be justified. But not making art made me feel bad so I had to engage in an act of faith, to ignore language and philosophy, to find my way back to art. And it was through making objects, that I started thinking about art, about its use value, and its ability to alter perception. So, language got me into a corner, but I found my way back to making art through a lot of faith, work and a little bit more language. I started thinking more with my fingers, with my hands. I became less self-conscious and more intuitive.

What achievements or milestones in your career and personal life bring you the most pride, and what aspects of your life do you feel the most gratitude for?

I love my friends and family. I cherish the fact that I am fortunate enough to make a life doing what I love. It’s incredible to have the freedom to pursue my passions and make my own rules. Perhaps I might want to spend a bit more time in nature. We’ll see if that becomes a reality. Time will tell, and I’m open to whatever comes my way.

Photo credit: © Fred Tomaselli, 2024. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

More images: