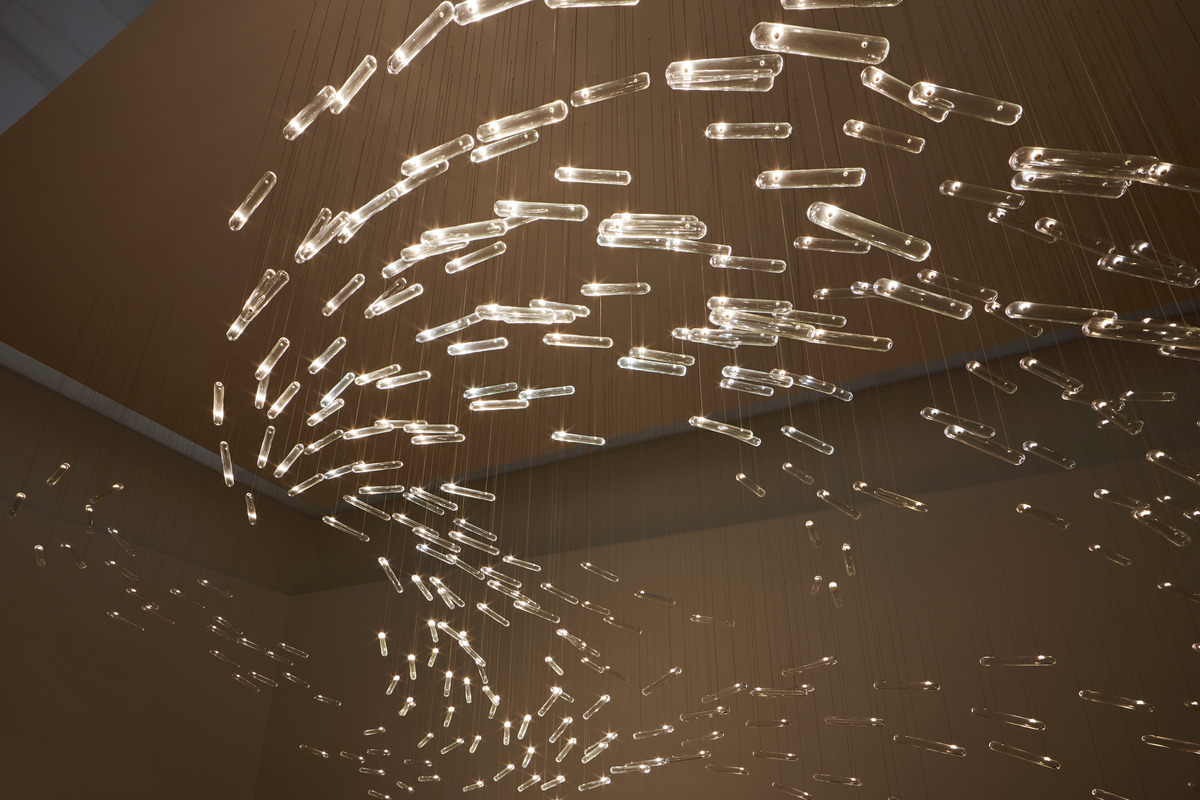

Several years ago, while visiting the Carpenters Workshop Gallery in their flagship on 5th Avenue in the heart of NYC, I came face to face with a true marvel – the ‘Fragile Future’ chandelier, a meticulously crafted dandelion seed composition.

Standing there, in sheer astonishment, I couldn’t help but inquire about the origins and the creative genius responsible for this breathtaking masterpiece. The chandelier’s intricate design had me entranced, creating a sensation of wonder and fascination as if I had momentarily forged a profound connection with nature amidst the bustling concrete jungle.

Today, with a very busy agenda, as they prepare for their upcoming shows and a mega project set to open in the Van Gendt Hallen in early 2025, I am delighted to share an exclusive conversation with Ralph Nauta, who graciously shared his time with Art Summit readers. He is one of the visionary artists, along with Lonneke Gordijn, who breathed life into DRIFT. We will delve into the mind of the creator and unravel the mysteries behind their mesmerizing creations.

About DRIFT

Dutch artists Lonneke Gordijn (1980) and Ralph Nauta (1978) founded studio DRIFT in 2007. With a multidisciplinary team of 65, they work on experiential sculptures, installations and performances.

DRIFT manifests the phenomena and hidden properties of nature with the use of technology in order to learn from the Earth’s underlying mechanisms, and to re-establish our connection to it. With both depth and simplicity, DRIFT’s artworks illuminate parallels between man-made and natural structures through deconstructive, interactive, and innovative processes. The artists raise fundamental questions about what life is and explore a positive scenario for the future.

All individual artworks have the ability to transform spaces. The confined parameters of a museum or a gallery do not always do justice to a body of work, rather it often comes to its potential in the public sphere or through architecture. DRIFT brings people, space and nature on to the same frequency, uniting audiences with experiences that inspire a reconnection to our planet.

DRIFT has realised numerous exhibitions and projects around the world. Their work has been exhibited at Biennale di Venezia (2015, 2022); The Shed (2021); Pace Gallery (2021), The Stedelijk Museum (2018); Victoria & Albert Museum (2009, 2015); Met Museum (2010); amongst others. Their work is held in the permanent collections of the LACMA; Rijksmuseum; SFMOMA; Stedelijk Museum; and Victoria & Albert Museum. In 2017, DRIFT was awarded Dezeen Designer of the Year.

An Interview with Ralph Nauta

By Carol Real

I’m truly grateful and delighted to have the opportunity to speak with you today. To start, I’d like to discuss a topic that you may have talked about frequently—your early days. If it’s alright with you, could you share your experiences from the founding of DRIFT in 2007? Additionally, I’m curious about how your collaboration on Fragile Future played a pivotal role in the birth of DRIFT and the inspirations that fueled this unique creative process. Would you be willing to share your insights on this journey?

Fragile Future is a work by Lonneke Gordijn, my partner. She graduated in 2005 from the Design Academy in Eindhoven, and this project originated from her final project. It all began when she had an old-style LED on her desk, and she noticed that the stem of a dandelion was the same size as the LED. This observation sparked the idea of creating a beautiful, elegant way to soften the harsh LED light. She started attaching dandelion seeds to the LED one by one with tweezers, essentially recreating the dandelion electronically.

During this time, we were both interested in exploring the relationship between nature and technology, a topic we often discussed at the Design Academy. I am fascinated by science fiction, while Lonneke is deeply interested in natural processes and materials. We were constantly trying to convince each other that these seemingly opposite worlds had a lot in common. This exploration of the overlap between nature and technology became a central theme in our conversations during our time at the academy.

Our education at the Design Academy was unique; it was more like an art school where we learned not only how to use materials but also how to develop new materials and production technologies. We were encouraged to think of innovative ways to create things and were held to high execution standards. It was a challenging education but one that set a high standard for our work.

After obtaining a space in Eindhoven from the city, we began developing multiple works simultaneously. At that point, we were not even familiar with galleries or selling our work. Our primary goal was to showcase our creations. Our first show was in Amsterdam, and when the gallery asked us about selling prices, we were unsure because our main focus was on exhibitions rather than sales.

Soon after, everyone from our school went to Milan to present their work, so we decided to do the same. We rented a space, produced our first ghost chairs, and embarked on a journey to Milan, driving at 100 kilometers per hour to save fuel. We even stayed at a campground, selling pieces on the spot to cover our expenses. This experience helped us build relationships and opened doors to exhibitions like Design Miami Basel.

During this time, we also connected with Carpenters Workshop Gallery which shared our vision of turning Fragile Future into a three-dimensional piece that could interact with spaces and surfaces. They believed in our idea and invested in it, marking the beginning of our journey with them. We grew our careers alongside this workshop, but we always felt that we didn’t quite fit into the traditional design world.

While we admired design’s innovation and material exploration, we couldn’t relate to its focus on functionality. Instead, we found a stronger connection to the art world. We learned more about the art world by attending fairs and museums and eventually connected with the Pace Gallery.

Fortunately, Pace Gallery saw the value in our work and thought outside the box, unlike many art institutions that would dismiss design. In those days, design was often misunderstood and associated with mass-produced furniture. We had to clarify that we weren’t traditional designers; we were artists with a background in design. Thankfully, times have changed, and design is now recognized as a crucial creative direction.

Our journey has continued, marked by a fusion of concepts and influences. My interest in science fiction, new materials, and technology combined with Lonneke’s passion for nature led to a harmonious partnership. We embraced the fusion of masculine and feminine energies, appreciating the beauty in their differences and learning from each other. This approach contrasts with the polarization we see in society today, while we believe in finding common ground and learning from diverse perspectives.

In essence, this philosophy forms the basis of DRIFT—the fusion of many elements, with a strong emphasis on the human component.

Can you elaborate on your approach to merging these seemingly disparate elements? Your work often blends art, design, and technology seamlessly. How do you view the distinctions between these disciplines in the context of your work?

Well, it’s also like we never think in that way. We don’t try to categorize creativity in a specific direction. I believe that’s an outdated way of thinking. Fortunately, things are changing now. Creativity, in its purest form, is simply what it is—thinking outside the box and discovering something that hasn’t been done before. This is also what I value in good art. If you find a new way to express yourself or a new material to work with, in any form, it should be something that’s never been attempted before. If it’s just a copy of something else, it lacks value.

I don’t look at art for inspiration; I consider that a form of stealing. Instead, I focus on my interests, especially those that I was drawn to as a child. When you’re young and free from politics or external influences trying to steer you in a certain direction, you see something that gives you goosebumps—that’s what should inspire you as a human being. I strive to remain connected to that source of inspiration.

Of course, everything we think of is influenced by something, but if my mind starts heading in a direction that someone else has already explored, I lose interest. I make my choices about what to focus on based on the idea that “Why hasn’t anyone thought of this before?'”

And then, I conduct research, and if it comes close to something that somebody has done, I think, “Okay, I’ll leave that aside and focus on something else.”

The materials that you incorporate—you use different materials in every single piece—are unique and distinctive. You also employ raw materials in their pure form. So, what is the significance of this choice in your artistic process?

Well, I don’t think like many traditional artists who specialize in one material and plan to work with it for the rest of their lives. I find that too limiting and, frankly, too boring. Moreover, it’s an easy way to find success in the art world. If you choose to, say, paint dots and continue doing that for the rest of your life, you’ll have plenty of time to market it, and it will become highly recognizable. Collectors and everyone else will relate to it. But for me, that’s too monotonous. I need to stimulate my mind to work on something. So, one year, I might explore something entirely different than the next. However, at this point in our careers, we’ve experimented with so many different things.

Yet, when I reflect upon it, there is still a similar underlying interest. I believe that when we eventually open the museum, you will see how everything comes together in a way that makes sense. So, now I understand why they chose that direction or why that particular piece was included. I think you can follow the thought process in that manner. It’s never solely about the material perspective. However, we do have a passion for exploring new materials that shape the world. They have a significant, profound impact on society. For instance, when something like concrete emerged back in the day, we suddenly could construct towering skyscrapers in conjunction with steel, and that allowed for the creation of diverse architectural forms. So, it’s all about the freedom that certain materials offer us to craft the sculptures or forms that pique our interest. Sometimes, we even find ourselves inventing new materials because we find existing ones too limiting.

And sometimes we come across a very interesting new material that somebody’s working on, and then we’re like, “Oh, that would be fantastic to work with.” We’ve done that with the Obsidian Project, for example. However, the one thing that best reflects our relationship with materials is probably materialism. It comes from this idea: How can you be bored in the world or life when there’s so much to discover? How can you not ask yourself questions? Like, when I’m sitting in a car, how does a combustion engine work? When I’m using my cell phone, how does it connect to Wi-Fi? What are the components needed for that? What is Wi-Fi, and how does the screen light up? How does that function? So, we start taking everything apart around us, trying to understand the ever more complicated worlds. That’s also the danger if you don’t do that–you might just expect everything to roll out of a factory and not see any value in it anymore, forgetting that there are hundreds of thousands of hours of people’s lives invested in creating these things you take for granted.

Someone dedicates their entire life to developing such technology and providing it to us. Why do they do it? What is the meaning behind it? Also, in a material sense, when you disassemble these objects, you can reduce them to their core materials. This allows you to trace where these materials came from and understand their influence on the world. What is their actual value, and how do they impact society? For instance, if you take apart a Rolex, you’ll find classical materials like steel, but also valuable ones like gold. However, these materials are often directly mined. On the other hand, if you disassemble a €15 Casio watch, you might initially think it has no value. However, you’ll discover that the plastic used in it was specifically created for a certain purpose, even in wartime. From a human perspective, this material may hold more value than gold. This perspective can give you a whole different outlook on life.

DRIFT’s work incorporates a variety of non-traditional materials. Could you please share your thoughts on the role that materials play in conveying your artistic message, especially when considering the use of raw materials in their purest form? How does this choice impact your artistic process?”

Again, I don’t know what “traditional” is or isn’t. Is it just like art? I don’t create art for other people; we create it for ourselves. And I think that’s something most good artists can relate to. You just have this urge to create, to build something, and to see it come to life. So you make it. It’s that simple.

And then when you see it flourishing, maybe after 10 years, because you’ve had the idea in your mind for a long time. In our case, we develop the technology ourselves or with partners to make the work happen because it’s never been done before. If it’s been done before, I’m not interested. I’m not interested in taking something off a shelf, like a drone with a light underneath, and saying, “Let’s do something with that.” I don’t think there’s any value in that; it’s already been done.

We thought differently back in the day. We had this algorithm, and we decided to put lights on the drones to have this physically in the sky. That’s why this technology didn’t exist before.

We began discussions with universities, and through collaboration with researchers who are now our partners, we developed the idea from scratch. Together with these partners, we built the technology that is now revolutionizing fireworks worldwide. It represents a different mindset, you know, but I’m eager to witness those drones in flight. I want to see them soaring with the algorithms we’ve created. That’s the intrinsic motivation–there’s nothing else to it. It’s all about wanting to see how it impacts people and whether it elicits the same reaction as I experience when I showcase something they’ve never seen before. And, well, that’s the fun of it.

How often do you find yourself saying, “Oh, this is not possible to achieve or realize,” or do you just keep trying until you find a way to make it work?

Lonneke and I work very differently in this regard. When I think of something, I immediately consider how I can technically solve it, and I can visualize it in my mind. Most of the time, we might end up heading in a different direction because it could be too expensive to develop. However, almost always, we come back to the core idea of how to build it. On the other hand, Lonneke has a more experimental approach. She follows a path, like a guiding light, such as an LED, without knowing the exact end result at first. Through research and experimentation, she eventually discovers the result. I have moments, like when I’m in the shower, where suddenly I get the idea to build something. I immediately know how to execute it, and it all starts to make sense at a certain point. I understand why and how, and everything falls into place. We have different ways of working, which we already experienced during our time at the academy. We know each other’s approaches, and while it sometimes leads to dialogue and discussions, most of the time, we find common ground and reach the result together.

That’s fantastic. What is it like working together with two different people, each with their unique perspectives and views? I mean, collaborating with individuals who may share a similar idea can still be a challenge.

It’s quite a challenge, but we rarely ever disagree on what a project needs to be. Sometimes, we do have disagreements about which projects we should prioritize, mainly because we only have a limited amount of time. These disagreements can lead to discussions about how far we want to push the technology. For instance, we might have a piece that currently does X, but we’re debating if it could potentially do Y with further development. So, there can be arguments about how much we should invest in a project before showing it or how far to push the tech before presenting it. These are conversations where we might have different ideas. However, we rarely disagree on the overall vision of what we want to achieve.

Perhaps the newer challenge for us is figuring out how a specific piece will come together visually in the end. Most of the time, we’re both excited about an idea and get those goosebumps, and that’s when we start discussing it with the team and begin developing the work. Time is always a limiting factor. We often wish we had a studio three times as big because there are so many ideas we want to explore.

Your work often involves interactive elements. How important is it for you to engage the audience and make them active participants in your installations?

It’s the main reason for me to create art installations. Seeing my work come to life is important, but what truly matters is having an impact on people who engage with it. Without that interaction, I might be doing something else entirely. My goal is to stimulate a thought process, to open people’s minds and make them say, “Wow, is that possible?” It’s not about creating imitators; it’s about inspiring individuals to believe that anything is achievable if they give their best effort. Some people may try to copy successful concepts for profit, but my focus is on encouraging the right mindset. It’s about revisiting childhood curiosity and building on it, playing with the world around you, and creating your own reality rather than conforming to an existing one.

We’ve always done this, never allowing ourselves to be restricted by institutions or curators trying to pigeonhole us because that’s their job. You should always create your own ideas.

The concept of the museum stems from this idea—pushing institutions to showcase our vision, even if some are receptive while others impose restrictions like specific lighting or music. We want to display the world as we see it; these creations are our brainchildren, our thoughts. So, it’s about establishing your own space without having to explain to anyone what you’re doing—just doing it. This level of freedom is something you have to claim for yourself rather than expecting it to be given to you.

In your statement, you mentioned that the DRIFT Museum represents the culmination of 17 years of work. Could you provide more details on how the museum’s design and content reflect the evolution of your artistic journey and your exploration of the intersection of art, technology, and nature?

I have already touched on this earlier, discussing how the museum reflects my personal interests and aspirations. However, throughout the process of creating our pieces, we discovered something significant. Instead of technology distancing us from our natural environment, we realized that it could be employed to bring people closer to it. We have conducted extensive research on natural frequencies and their relationship to the viewers’ experience. Our goal is to alter people’s states of mind and open them up to a collective connection rather than using technology to isolate us from one another.

For instance, consider social media, which is often referred to as “social,” but in reality, it tends to be asocial. It often makes us feel like isolated individuals, each clamoring for attention. It becomes all about “me, me, me” rather than fostering a sense of community. We believe there are ways to utilize technology differently.

We’ve been contemplating the idea of building this museum for nearly a decade, even before the emergence of many immersive museums. Unfortunately, some of these newer immersive art spaces prioritize profits and cut corners to achieve rapid financial success. They focus on cost-effective solutions, relying heavily on animated projections and mapping projectors. This approach may provide quick results, but it risks giving the immersive art movement a bad reputation.

In contrast, creating true spiritual and meaningful experiences often takes time and depth of thought, much like embarking on a month-long journey in the Himalayas for profound insights, rather than seeking shortcuts like a weekend ayahuasca session. We believe in a more profound and meaningful approach to art and technology, which is what we aim to offer at the DRIFT Museum.

The same goes for all of this, including digital arts. It appears shallow because you can’t physically touch it. It’s intangible, elusive. What we specialize in is entirely physical—robotics, large sculptures, and technology that we’ve designed ourselves—all rooted in the tangible world. It takes much longer to create, but that’s the essence of it.

The issue we’re facing today, in our overall culture, is that everything is digitized and fast-paced. It’s a continuous cycle of copies, lacking the time to grow and reach its full potential. In the past, before the digital age and social media, we had decades to nurture movements—the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s—each era had its unique identity. But now, post-2000, it’s all a blur, recycling the past with nothing truly new.

So, we’re striving to preserve that uniqueness and protect our interests, but it’s challenging. We get copied a lot, even within the art tech movement. We were pioneering interactive art as far back as 2006. People used to look at Lonneke’s work, her last name means curtain in Dutch, and say, ‘I don’t understand, it’s just a curtain.’

However, we’ve come a long way from there. It’s challenging to safeguard the deeper meaning while navigating today’s fast-paced world. Instead of perfecting their creations, many rush to market or showcase them at 50% potential due to the fear of missing out. We’re different. We’re committed to refining our pieces, hammering them out, and continually working on new projects.

With the upcoming museum, we hope people will be pleasantly surprised by our body of work. Let’s see.

What inspired you to choose the 19th-century Van Gen Hallen as the location for this project, and how does its history contribute to the overall concept of DRIFT’s art?

The first time I stood in front of this building was eight years ago. I remember telling my girlfriend, who is now the mother of our second child, during our first date that we were going to build our museum here. She thought it was crazy, but fortunately, it became a reality. This historical building used to be a place where they manufactured old steam engines and large pumps to reclaim land from the sea in the Netherlands. It has a rich history, and when you walk in, it still carries that industrial and high-tech vibe. Our art pieces are substantial, so we needed a space like this. There were other options, but this building had so much soul and history in it, with its DNA rooted in innovation.

Unfortunately, at one point, an entrepreneur bought the building next door, which was a bit of a setback. However, about four years ago, one of my colleagues, who had worked for him, suggested that we reach out and see if we could collaborate. I had to put my ego aside because I didn’t particularly like the guy for buying up my dream buildings, but we had a meeting, and it turned out we shared a vision for what this space could become. Now, we’re partners in this endeavor, and it’s been an incredible journey.

Potentially, it’s the largest historical building that’s being rebuilt as an energy-neutral structure. It has the most high-tech installations and the most advanced materials developed within the building. We’re building the structure from the core out, with walls made of bio-based anti-inflammatory insulation material called Dup core, which is fantastic. It’s made from recycled bottles and seaweed. We produce these panels in a mini factory within the building. So, it’s an exciting and innovative project.

One of the museum’s goals is to generate wonder and emotional responses from visitors, fostering a deeper connection to our planet and nature. How do you envision achieving this goal through the museum’s exhibits and activities, and what kind of experiences are you aiming to create for your visitors?

We aim to induce a different emotional state in people. Often, when individuals visit, they are preoccupied with their daily lives, constantly tethered to their digital devices, and unaware of their surroundings. People may rush from one historical monument to another in a city without truly being present. We strive to pull people out of their smartphones and immerse them in the real, physical world. Ideally, when they leave, they will have a transformed mindset. It’s akin to the feeling of visiting the ocean, the beach, or the mountains—an attempt to alter one’s state of mind.

This is important because during these moments individuals can contemplate what truly matters in life. These precious moments are why many seek to escape city life and reconnect with nature to rediscover their values and align with themselves. It’s something we often forget, even after brief escapes into nature. Upon returning home, we are swiftly drawn back into the rat race and forget the significance of our connection to the environment. Only when you are in tune with your surroundings can you make the right decisions in life, and your core will guide you toward those decisions.

Being connected to your environment is crucial because it shields you from the influence of marketing and those who see you as a mere source of profit. Protecting oneself from such influences is only possible when one is in the right conscious state. We hope to contribute to this shift, particularly for those who cannot travel extensively or experience natural settings. We aspire to provide everyone with the opportunity to encounter magic in the same way that I have had the privilege to experience it.

The moment I first saw the dandelion chandelier at Carpenter’s Workshop a few years ago, it was a unique and astonishing experience. Here’s the remarkable part: whenever your work is brought up in conversation, the unanimous consensus is that it’s nothing short of extraordinary.

It’s interesting that you say this because you’re already seeking those connections, right? I mean, it’s your personal interest. That’s why you’re investigating art in that way—like you’re trying to discover what is real in the world and what makes you feel connected. The people you connect with recognize this because they’ve had a similar experience. However, I believe it’s our responsibility as creatives to reach as many people as possible who may not be thinking in that way. This way, we can open up their minds in a certain way and help them start making the right choices in life. I think that’s very important, and perhaps it’s a part of all of this.

Photo credit: Courtesy of © Studio Drift

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

More images: