Artist’s Biography

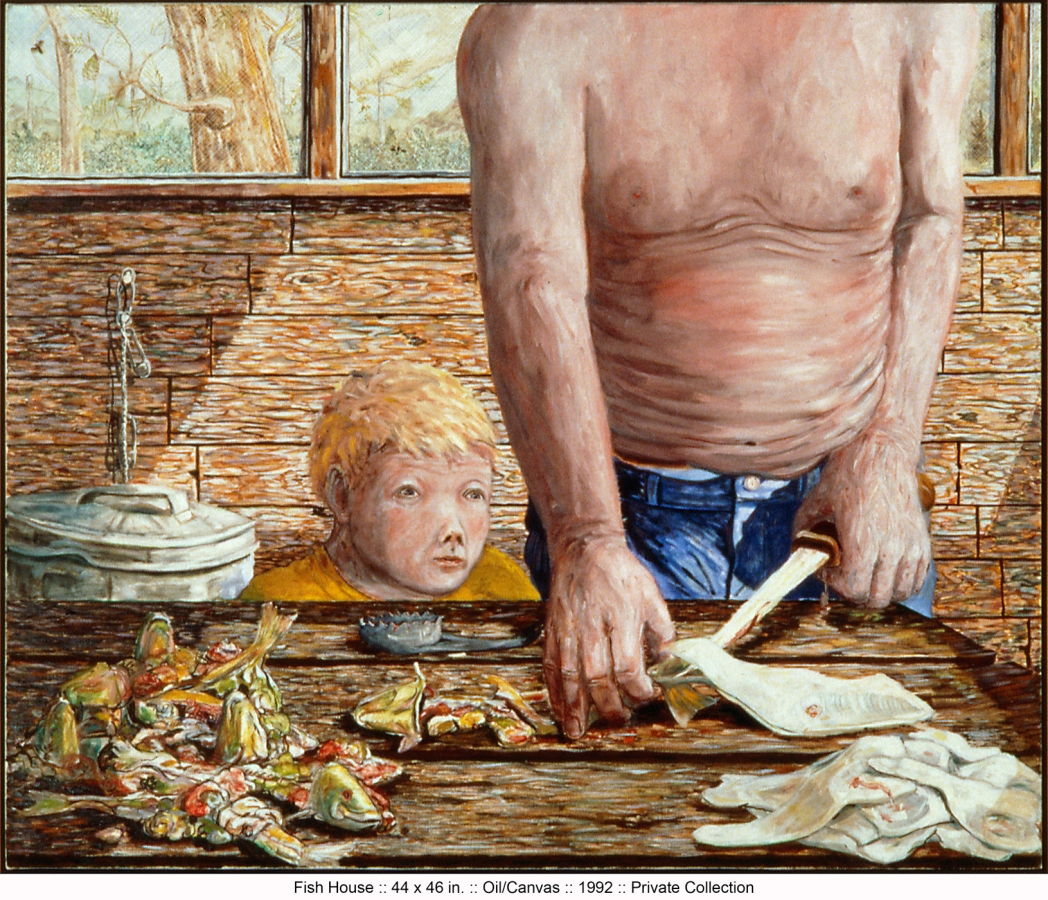

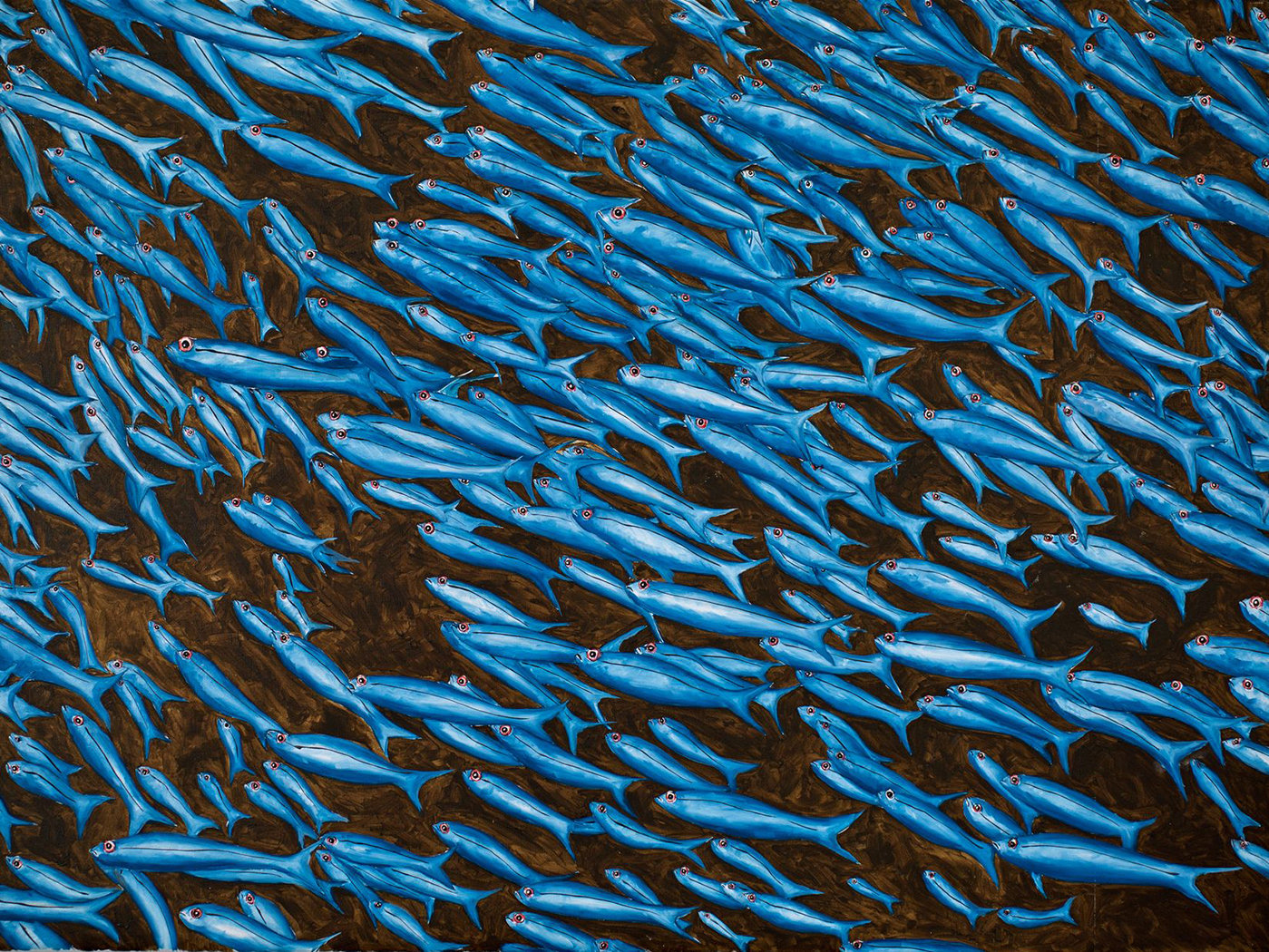

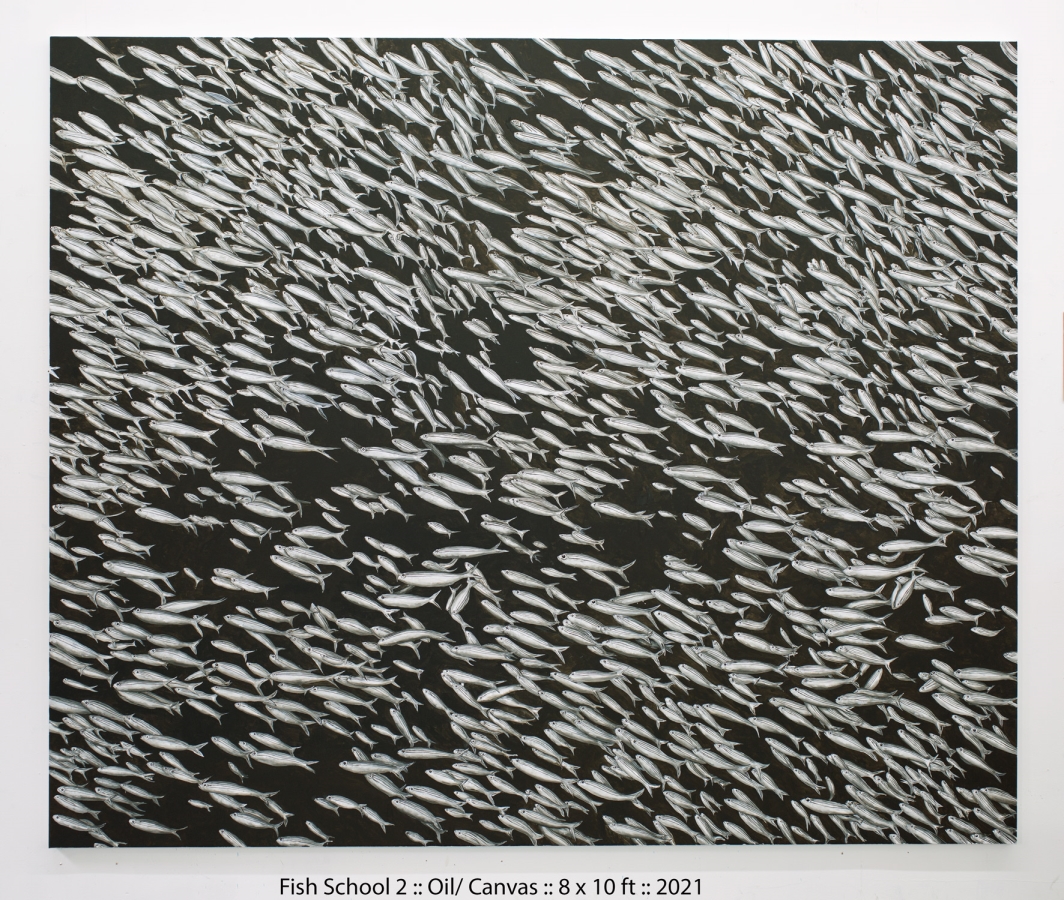

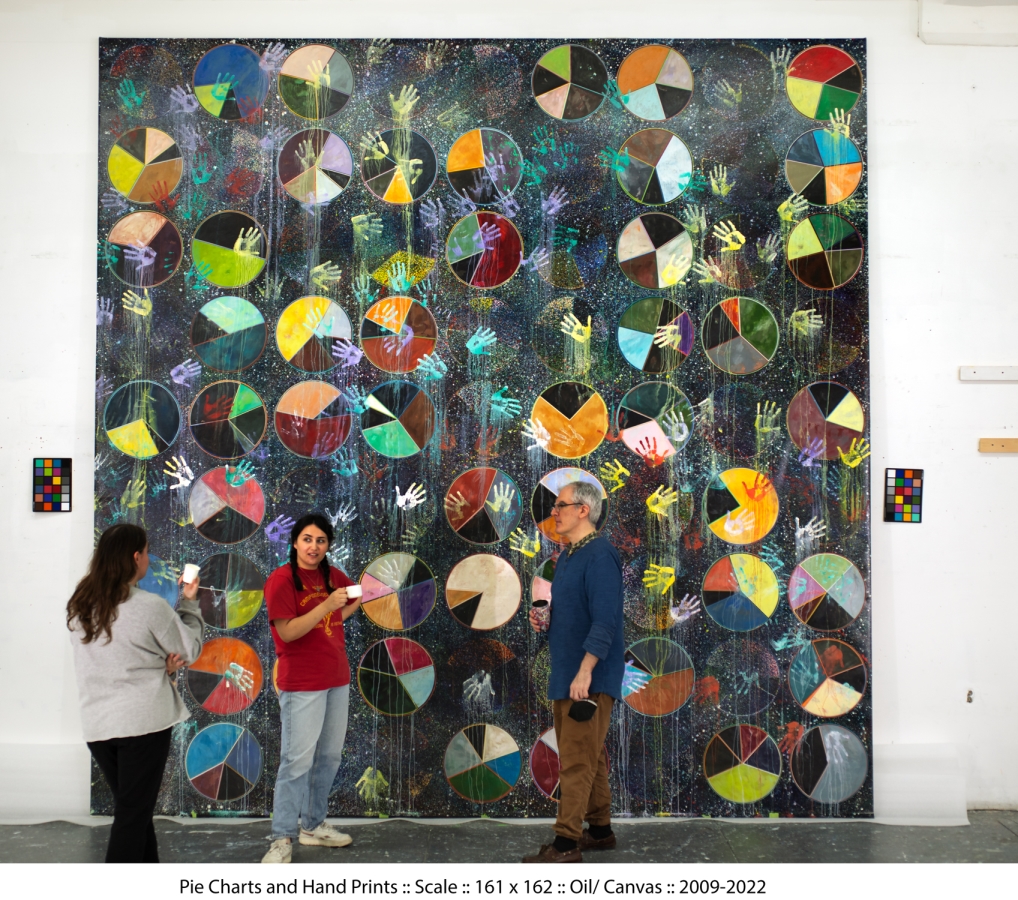

BORN IN ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA, New York City-based artist Doug Argue’s thirty-year painting career has culminated in a striking body of abstract work that encompasses a diversity of mediums and formats. His compositional approach extends to both spatial construction and figural depiction in an oeuvre that lyrically conjures metaphors and art-historical references to the past and present.

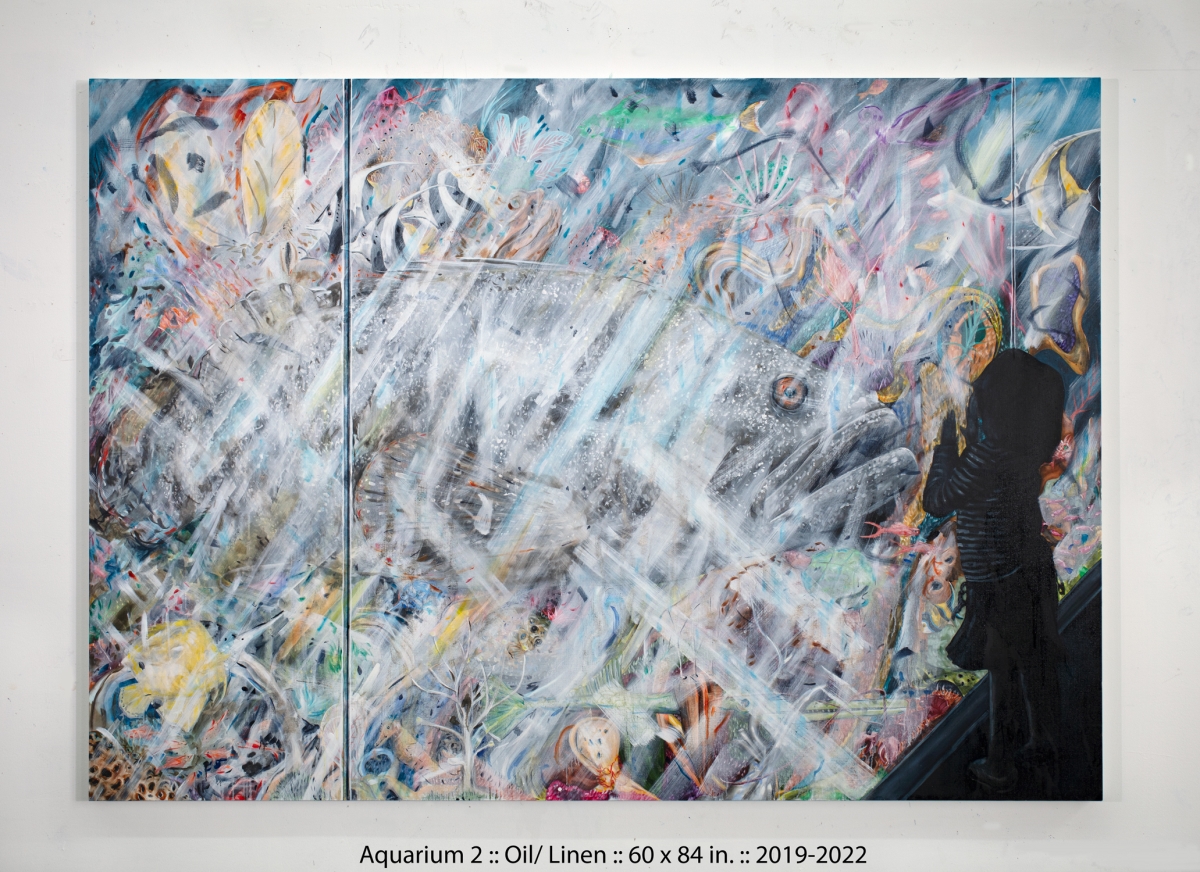

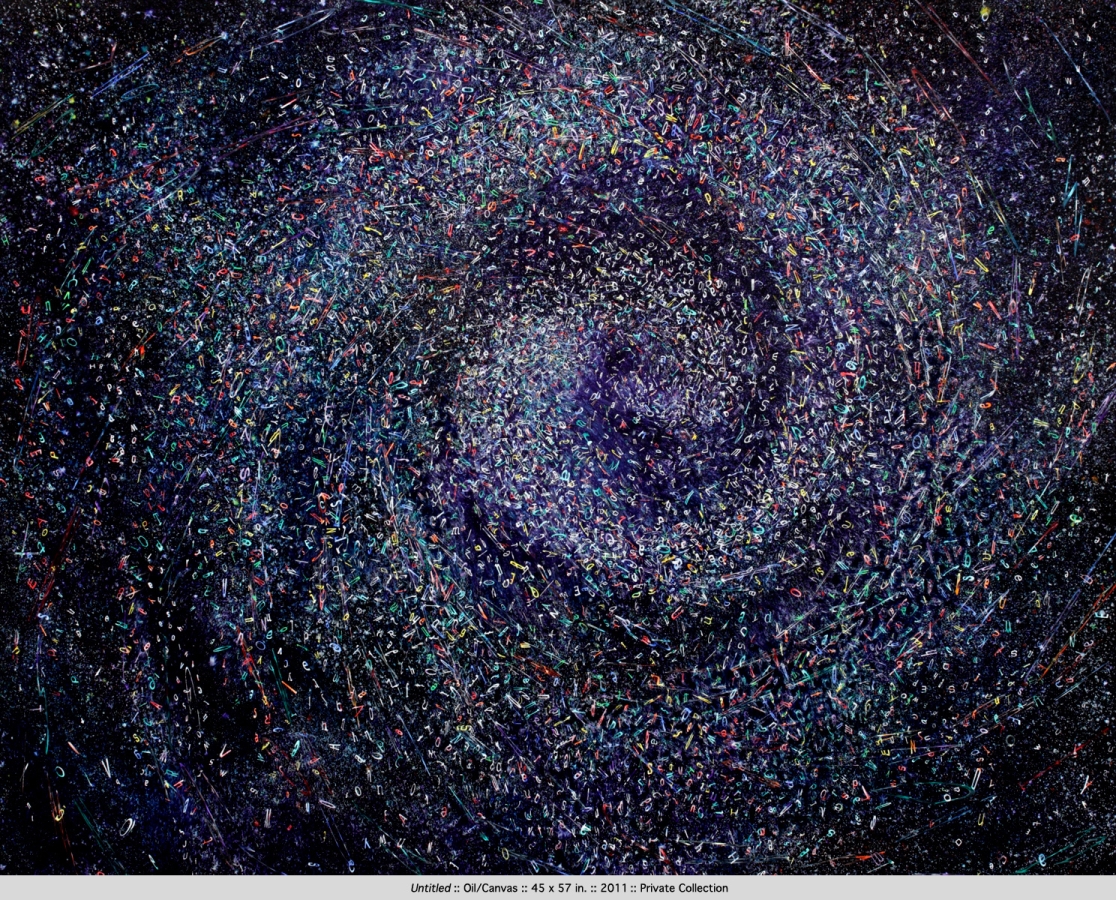

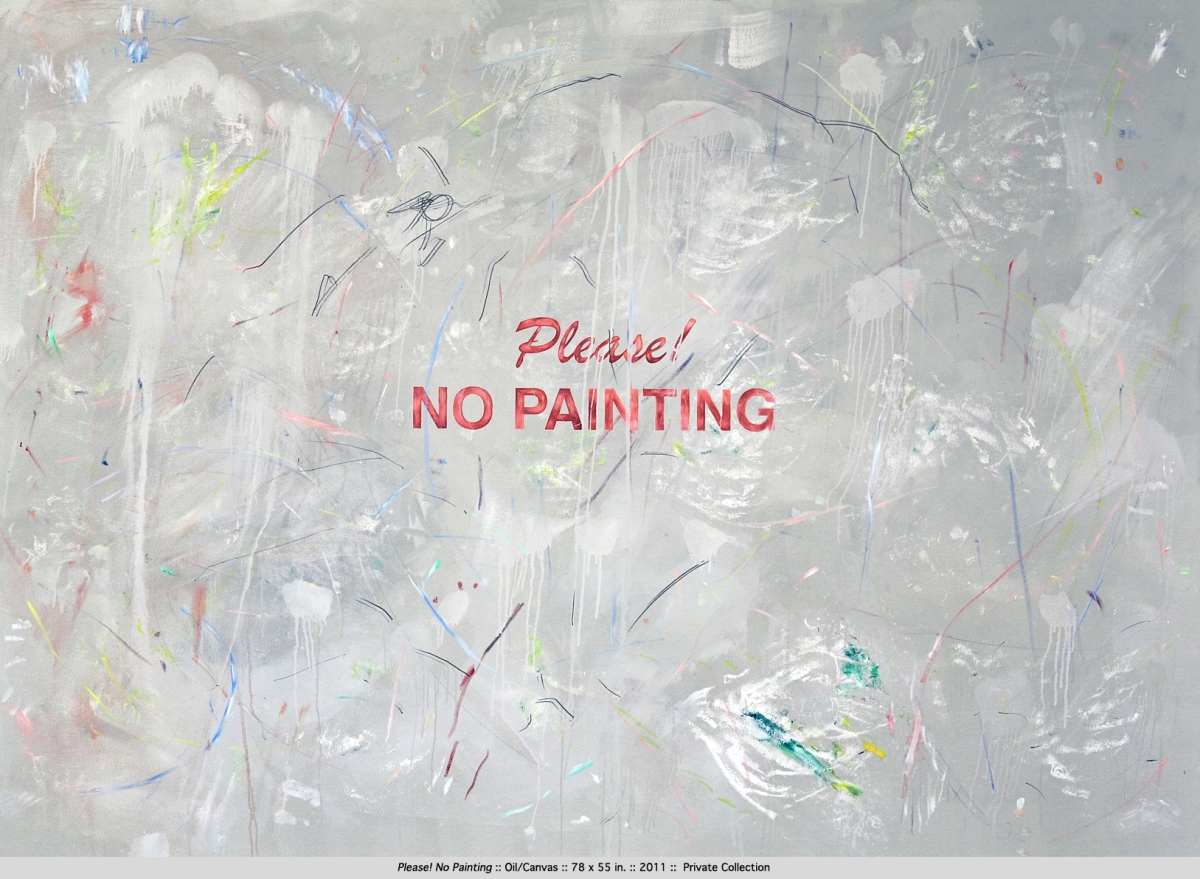

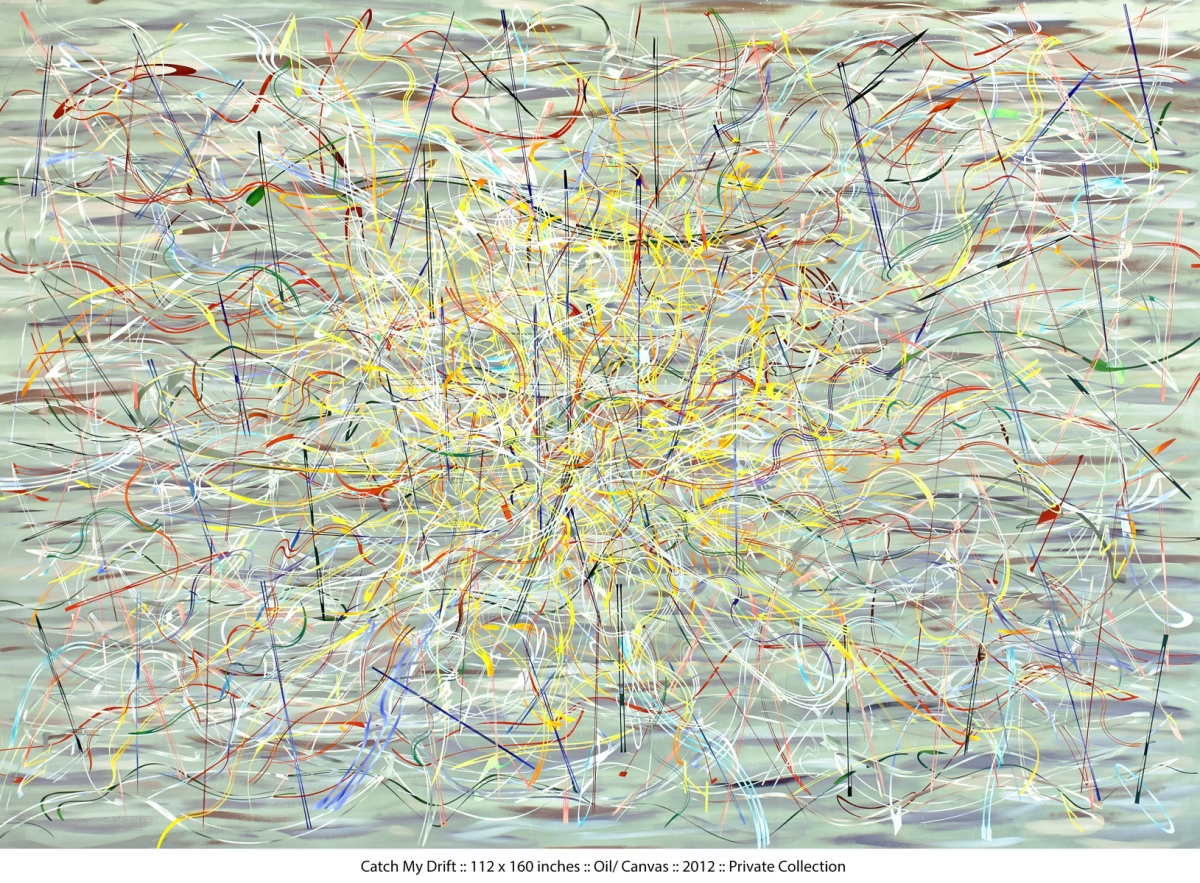

In his most recent work, fluid orchestrations of biomorphic forms and geometric shapes, amidst spontaneous gestural swaths of color are swept over different pictorial depths and surfaces suggesting movement, instability, and the passage of time. Integral to Argue’s vocabulary of shapes, computer-generated stencils of scattered letters dissipate across these illusionistic fields to form their own lexical cosmos.

Culled from literary classics such as Moby-Dick to sonnets by thirteenth century poet Petrarch, Argue’s atomized texts are inspired by psycholinguistic and scientific phenomena. The artist explores abstraction syntactically: paragraphs, sentences, and words compose and decompose into one another, until they are only discrete letters; stretched and skewed, elastic and malleable as meaning itself.

“There are many different histories in the world, in both art and politics, and we often see things in the current moment, yet have no idea what lies beneath. One language is always turning into another, one generation is always rising and another falling, there is no still moment. I am trying to express this flux—this constant shifting of one thing over another, like a veil over the moment itself.”

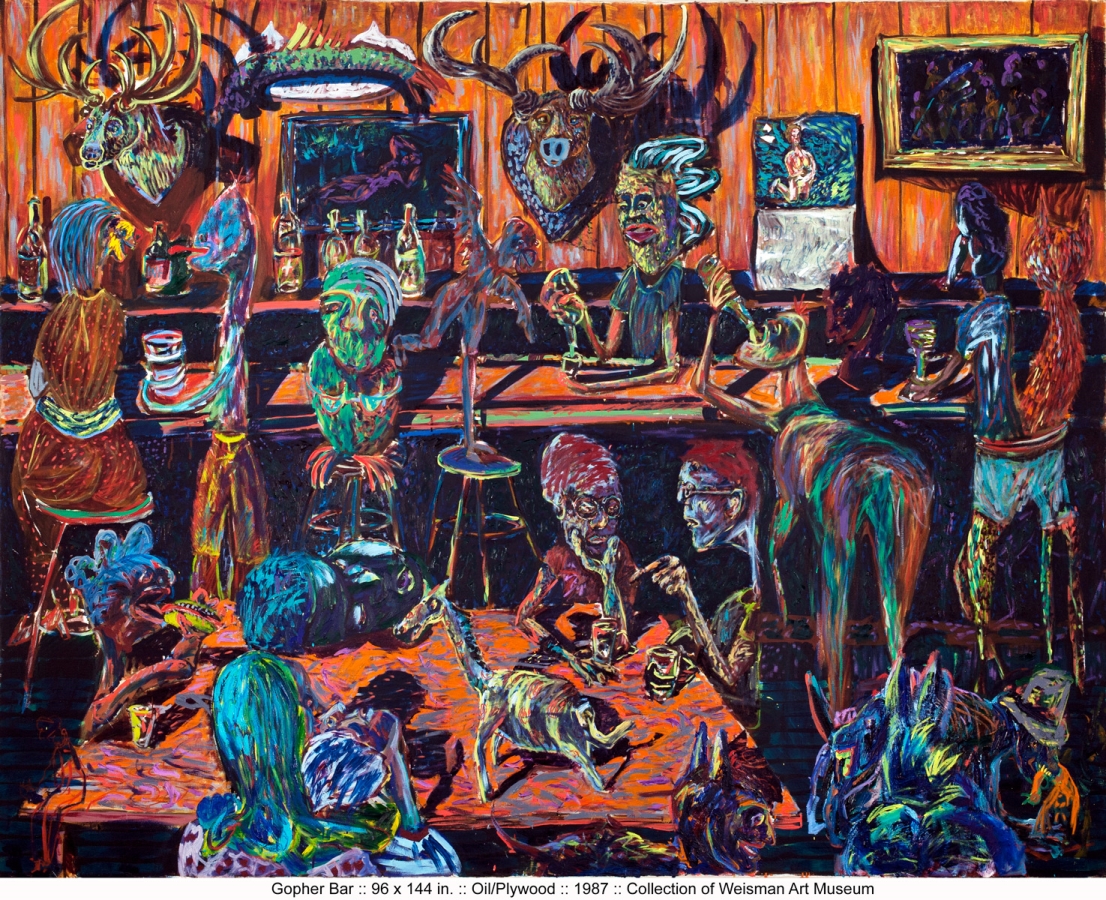

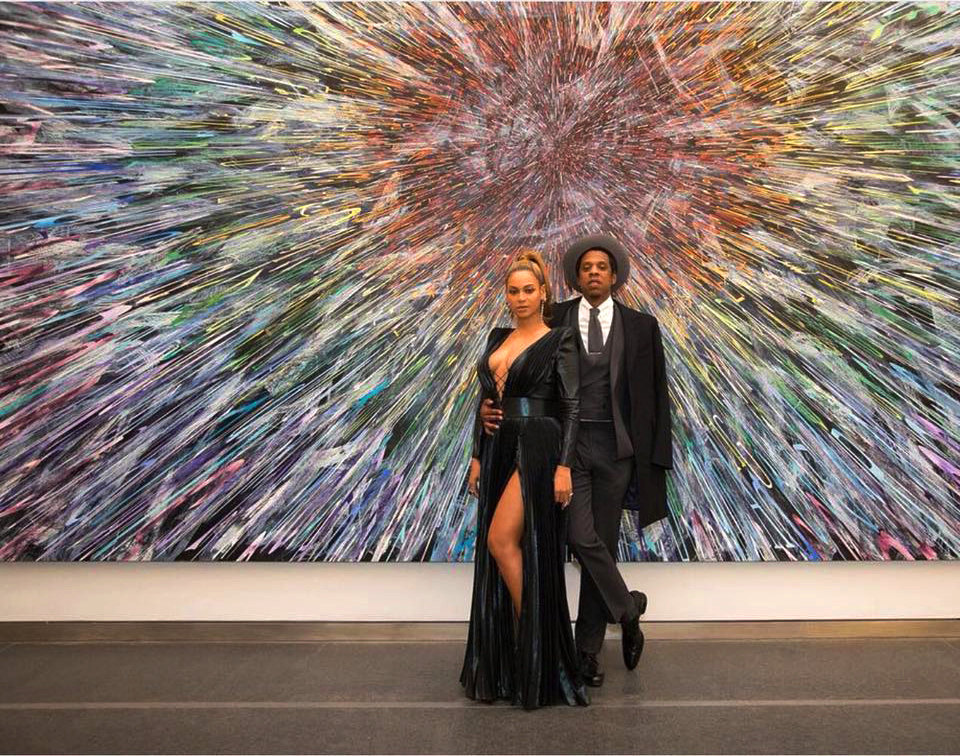

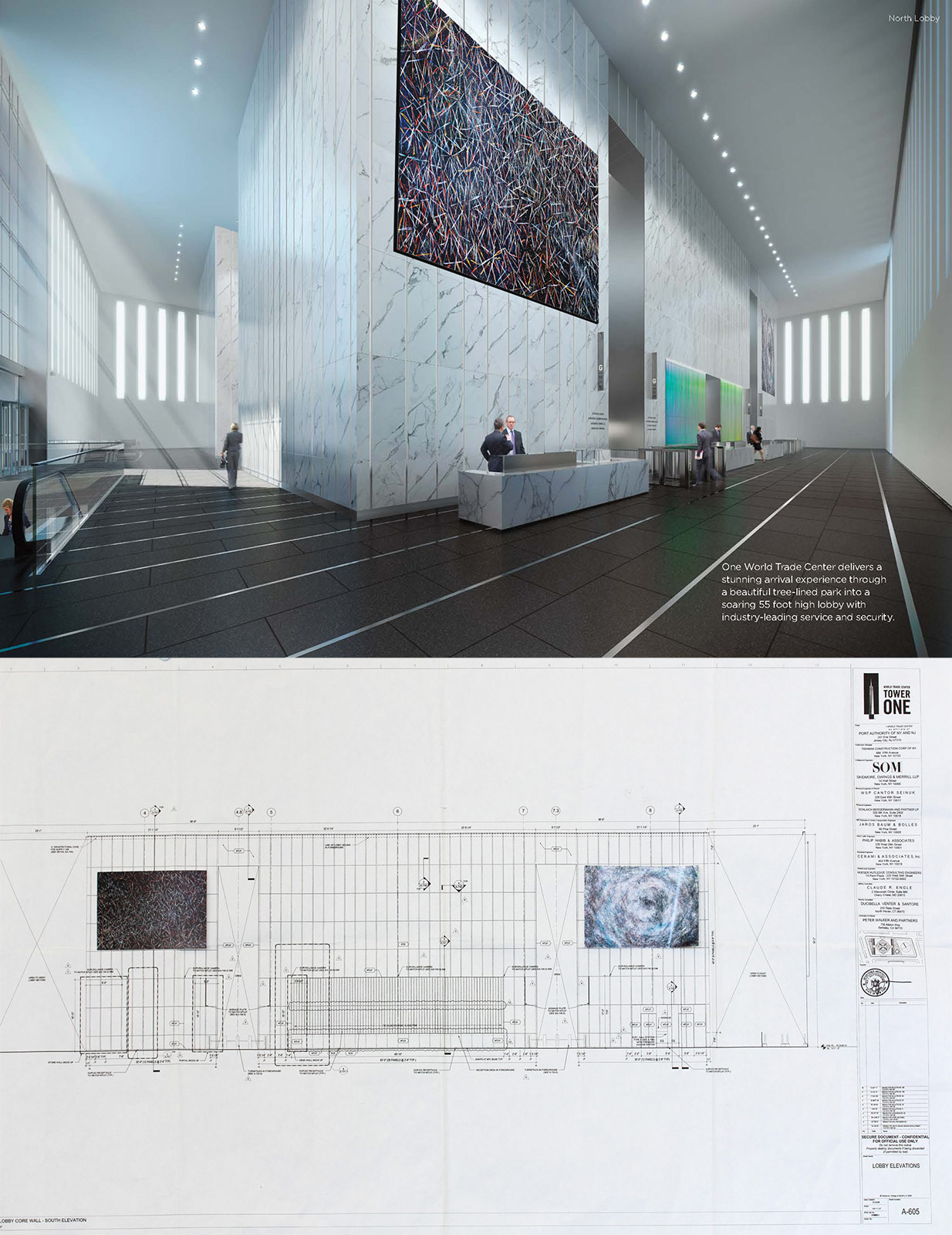

Argue’s work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions including at the Richard Heller Gallery, Santa Monica, and in New York, Edelman Arts and Haunch of Venison. Most recently, two of his paintings were commissioned for the lobby of One World Trade Center in Manhattan. His work is held in the collections of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Walker Art Center, Weisman Art Museum, and numerous corporate and private collections. Argue has been the recipient of multiple awards including a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant (1995) and the Rome Prize (1997).

Bio source https://www.dougargue.com/bio/

Interview

Artist: Doug Argue

How was the transition of moving from Minneapolis to New York City? What did you encounter when you arrived in NYC?

In 1998, I won the Rome Prize and moved to Rome for a year, and in 2001, I moved to San Francisco for 10 years. So I had some experience of living outside of Minneapolis before arriving in New York. When I moved to New York I signed a contract with two big galleries—one in Chelsea and the other on the Upper East Side. They sold almost all the work I had done for the past ten years. It was a big change for me in that context. I’ve always loved New York, with its 800 plus languages spoken. It’s a beautiful multi-cultural city, and I feel at home here: little old me disappearing in the multitude. I have supporters and dear friends in Minnesota who’ve continued all these years to buy work, and support me, and the same is true for San Francisco. I’m very, very grateful for the long-term relationships but the possibilities in New York are so much greater than anywhere else in the world.

Who or what has been the biggest influence on your approach to art?

I like the idea that art is a bridge between generations so there is not an abrupt start and finish to culture as we live and die. Every generation forges ahead and dismisses the old, but art can be something that bridges the time between the lives and deaths of people and allows for the feeling of a continuation of culture even as it changes. I’m not one of those people who doesn’t like museums. I like how they act as a window into the past and future and allow me to mingle with artists long dead and yet to be born. I’m assuming a continuation in the future here; I’m not speaking literally of course. The same is true with writing and poetry, which has been one of the great joys in my life. We have genetic knowledge which literally builds us from the ground up, bones, heart, and mind, without a bit of thought from us, and of course gives us language. We have the sciences with their cumulative everchanging gift of knowledge, but in art of all kinds we get a sense of what it was like for someone to be alive—an experience. I think it helps us to feel less alone and adds the spice to life. It’s also another way of passing on ideas and thoughts outside of genetics and biology.

How did your interest in literature begin and how did it influence your work?

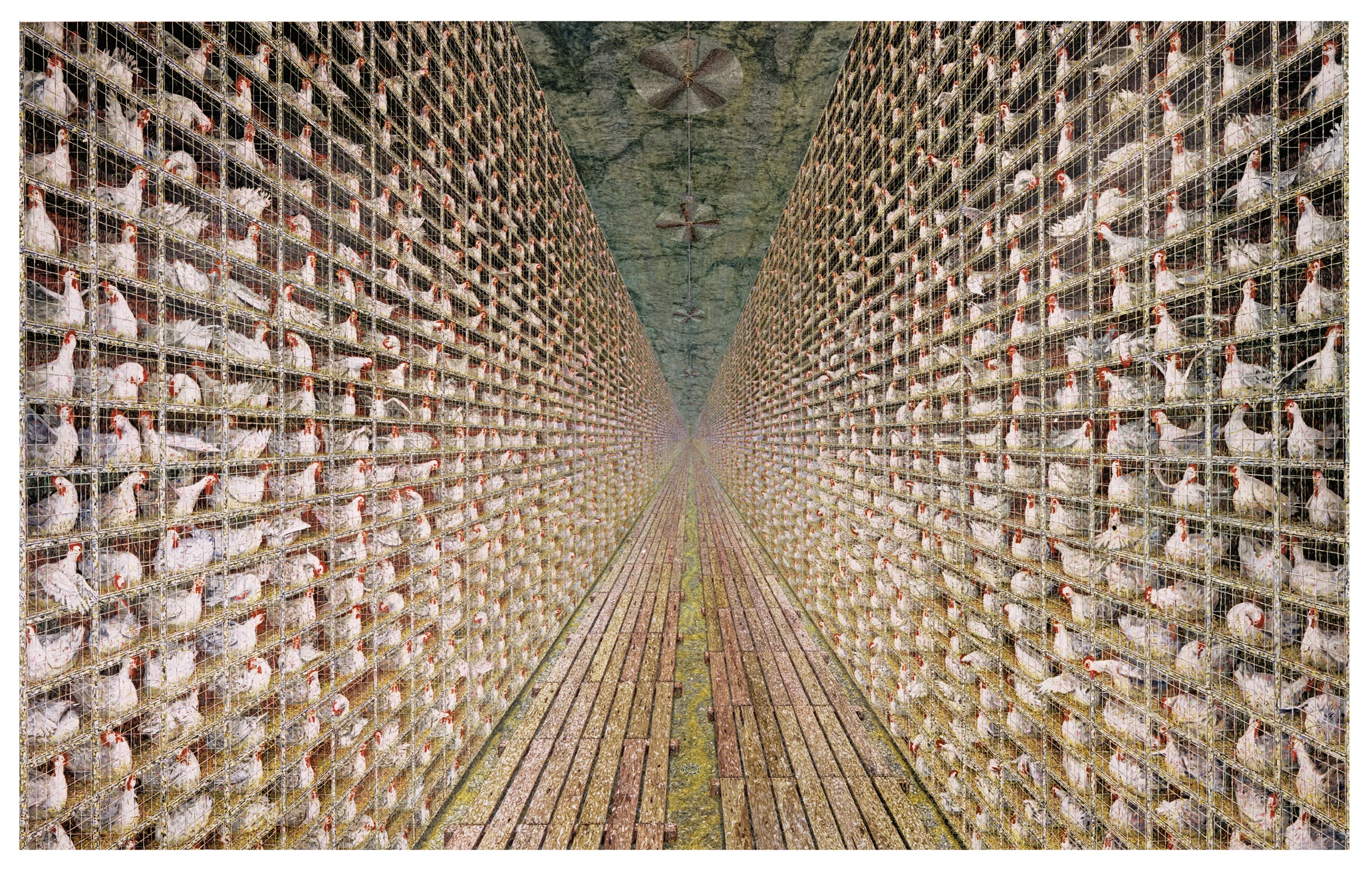

I have always been interested in literature and poetry. It’s just something that’s always been a part of my life. At a very young age, I was reading James Michener for hours on end in the warm bath. Hawaii was born, evolved, and was populated with people and creatures right before my eyes. You can both escape from the world, learn, and be more in the world at the same time. Someone said it’s the gaps between words where the meanings lie, and that’s certainly often true in poetry. In the beginning, it influenced my work by creating these complete imaginative worlds in each painting, almost the way a poem or a novel does. A lot of my ideas for paintings come to me when I’m reading, and I pause and daydream based on the reading. For example, when I did the large painting of chickens, I was reading a Kafka short story about a dancing dog whose owner played an organ grinder on the street. Meanwhile the dog, wearing a tutu, danced for tips and contemplated how he got his food is related to who he was as a dog. I daydreamed in my mind about where I got my food and saw the image of the chickens exactly in my mind’s eye, and then it took three years to paint it.

What interests you about the idea of “particulate matter”?

Matter is particulate. There are a limited number of elements, about ninety I think, and that limited number combines and recombines to make all matter. The atom is the basic unit of the element and is the building block of all matter, and so life as we know it, and combines in various ways to make up all matter. Language is genetic and is encoded in human babies at birth. Writing systems are a human invention, and the Roman alphabet works in a very similar way as atoms do, where the letters can be combined and recombined in an almost infinite number of ways. This allows every person and every generation to say something different and still be understood. It seemed to me that I could draw a comparison between the basic building blocks of culture in terms of letters, and the basic building blocks of the universe which are atoms. Both are systems that allow for constant flux and change as they recombine in different ways. This is not science but the idea has worked very well for me in making some very good paintings.

How would you describe your personal style?

I try and see what comes next for me and embrace the change. Since I am a maker, everything is always connected.

Which one of your paintings are you most proud of?

Well, that’s impossible. I would just say I’m usually most interested in whatever I’m working on because it’s more present.

Your paintings are very large, taking up whole walls. Can you discuss the importance of scale in your work?

I do lots of smaller works as well but not a lot of people can make the big ones anymore, so I think it does stand out. What interested me after I saw some large Tintoretto paintings in Venice was how that scale of those paintings were outside of my peripheral vision; it pushed my eyes to the edges and I couldn’t take in the whole. I like that experience of being enveloped and swallowed up into the painting. I have always been interested in the idea of infinity, and I’ve always wanted to push the sides and the edges of a painting so it feels like they can keep going forever. I first thought of this after looking at a lot of early Asian paintings where the landscapes are dominant and seem like they extend in every direction endlessly. The people are decentralized and scattered through the forests or the house. Working in a large scale and exploring infinity are combined with the idea of the group—of large numbers of individuals all slightly different—as opposed to a centralized important individual like Napoleon on his horse.

Your style is very distinctive and unique; it has inspired younger generations of artists. What advice would you give to someone just starting a career in art?

The best advice I ever heard was from David Bowie; I think I saw it on Tik Tok, where he said “never work for other people…always remember that the reason that you initially started working was that there was something inside yourself that you felt that if you could manifest it in some way you would understand more about yourself and how you coexist with the rest of the society…I think it’s terribly dangerous for an artist to fulfill other people’s expectations. I think they produce their worst work when they do.”

After 30 years of a prodigious and successful career exhibiting in cutting-edge galleries and museums, what else is left to do?

I have lots of ideas for new paintings, and a grandson who I hope will enjoy listening to me tell all my crazy stories. I would hope that I could open different possibilities and realities in his curious mind.

What can you tell us about your upcoming retrospective at the Weisman Art Museum?

The Weisman Art Museum is Frank Gehry’s first museum building and part of the University of Minnesota, where I went to school. I have not had any exhibitions that combined the work that I’m known for in the Twin Cities where I lived and worked there for 20 years, and the work I did in San Francisco and in New York. I’m looking forward to seeing the show myself. I think and hope people will have fun making all the mental leaps and connections that I made when I created them.

Favorite quote

Excerpt from The Tenth Duino Elegy

Someday, emerging at last from the violent insight,

let me sing out jubilation and praise to assenting angels.

Let not even one of the clearly-struck hammers of my heart

fail to sound because of a slack, a doubtful,

or a broken string. Let my joyfully streaming face

make me more radiant; let my hidden weeping arise

and blossom. How dear you will be to me then, you nights

of anguish. Why didn’t I kneel more deeply to accept you,

inconsolable sisters, and surrendering, lose myself

in your loosened hair. How we squander our hours of pain.

How we gaze beyond them into the bitter duration

to see if they have an end. Though they are really

our winter-enduring foliage, our dark evergreen,

one season in our inner year –, not only a season

in time –, but are place and settlement, foundation and soil and home.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Artist website Doug Argue

Editor: Kristen Evangelista