Artist Bio

Born in Osaka, Japan (1972), lives and works in Berlin.

Confronting fundamental human concerns such as life, death and relationships, Shiota explores human existence throughout various dimensions by creating an existence in the absence either in her large-scale thread installations that include a variety of common objects and external memorabilia or through her drawings, sculptures, photography and videos.

In 2008, she received the Art Encouragement Prize from the Japanese Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Her solo exhibitions across the world include Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2019); Gropius Bau, Berlin (2019); Art Gallery of South Australia (2018); Yorkshire Sculpture Park, UK (2018); Power Station of Art, Shanghai (2017); K21 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf (2015); Smithsonian Institution Arthur M.Sackler Gallery, Washington DC (2014); the Museum of Art, Kochi (2013); and the National Museum of Art, Osaka (2008) among others. She has also participated in numerous international exhibitions such as Oku-Noto International Art Festival (2017), Sydney Biennale (2016), Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale (2009) and Yokohama Triennale (2001). In 2015, Shiota was selected to represent Japan at the 56th Venice Biennale.

Bio source: https://www.chiharu-shiota.com/profile

Interview

Artist: Chiharu Shiota

By Carol Real

Let’s talk about your childhood. What memories do you have of your upbringing in Japan?

I was born in Osaka but my parents’ house was in the countryside. I always played outside, picked flowers, or played with the earth. I made a kind of vegetable shop with handmade mud squares and flowers or grass. We went fishing and spent a lot of time in nature. While I spent a lot of time alone and created my own world, I also played with friends.

What led you to decide to become an artist?

My parents owned a small factory and I saw the factory workers every day. They were making a lot of fish boxes every day and they were working with machines, almost becoming like machines. I started to think that I wanted to do more spiritual and creative work, and then I decided to become an artist. When I had my first solo exhibition as a student, I felt like an artist.

Installation: metal frame piano, white wool, note sheets.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, UK Courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Ph Jonty Wilde. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation, white wool, wire, string.

Le Bon Marché, Paris, France

Ph Gabriel de la Chapelle. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: wool, paper.

Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, São Paulo, Brazil.

Ph Atelier Chiharu Shiota. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Many parents think that it is better to follow a traditional career rather than an artistic one for fear that an artist will not be able to make a living. Were your parents supportive? If not, did you ever feel that it would be better to listen to your family instead of following your own calling?

My parents didn’t stop me from becoming an artist and they were never against it. I was quite sure when I was 12 years old. I could make drawings better than other children and my teacher complimented my skills. I was never worried about how to live, and I was sure I could live through my art.

Can you describe the impact of your move to Berlin in 1999? How did you handle this transition?

Berlin had a different energy after the wall fell. There was construction everywhere and so many artists and curators came to Berlin. It was a mixed culture—people were poor but sexy. All these art shows were happening in old buildings and in basements. I thought I could be myself. I could create my artwork and just have

exhibitions.

WinX Tower, Frankfurt/Main, Germany

commissioned by WinX GmbH & Co Immobilien KG, Bad Homburg.

Ph Klaus Helbig. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: rope, paper, steel.

König Galerie, Berlin, Germany

Ph Sunhi Mang. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

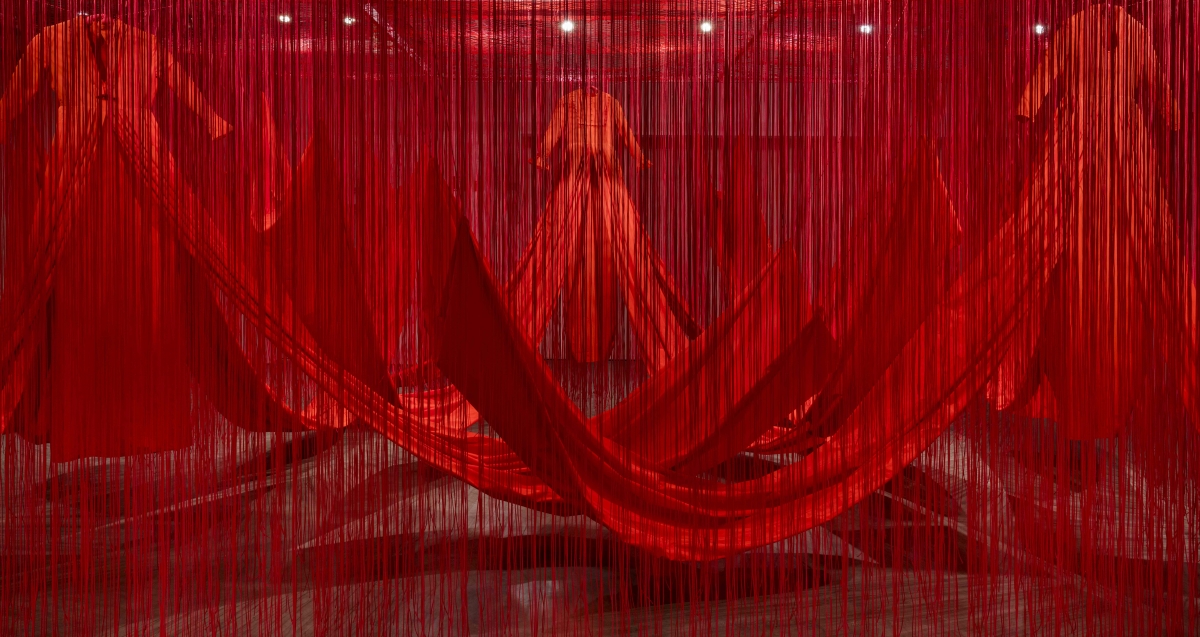

Installation: red fabric, rope.

Japan House, São Paulo, Brazil

Ph Ding Musa. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

You began your career as a painter, then you focused on performance and now you shifted to site-specific installations. Which of these disciplines feels more comfortable?

I am an installation artist but almost every day I create drawings too. I began drawing again after my first cancer diagnosis. When visitors come to the room, they are immediately surrounded. Suddenly, I can immerse their whole body in my art space—it is like a drawing in the air.

It’s all about connections and connecting souls. What are the emotions involved in the creation of your works?

If you are living in this society, you are connected and when someone dies, their memory is even stronger. I believe everyone is connected with an invisible thread.

Cisternerne, Muserne Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Ph Torben Eskerod. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: thank-you letters, black wool. Kunsthalle Rostock, Germany

Ph Thomas Häntzschel, Fotoagentur Nordlicht, Rostock. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: dresses, black wool.

Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Aichi, Japan.

Ph Kazuo Fukunaga. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

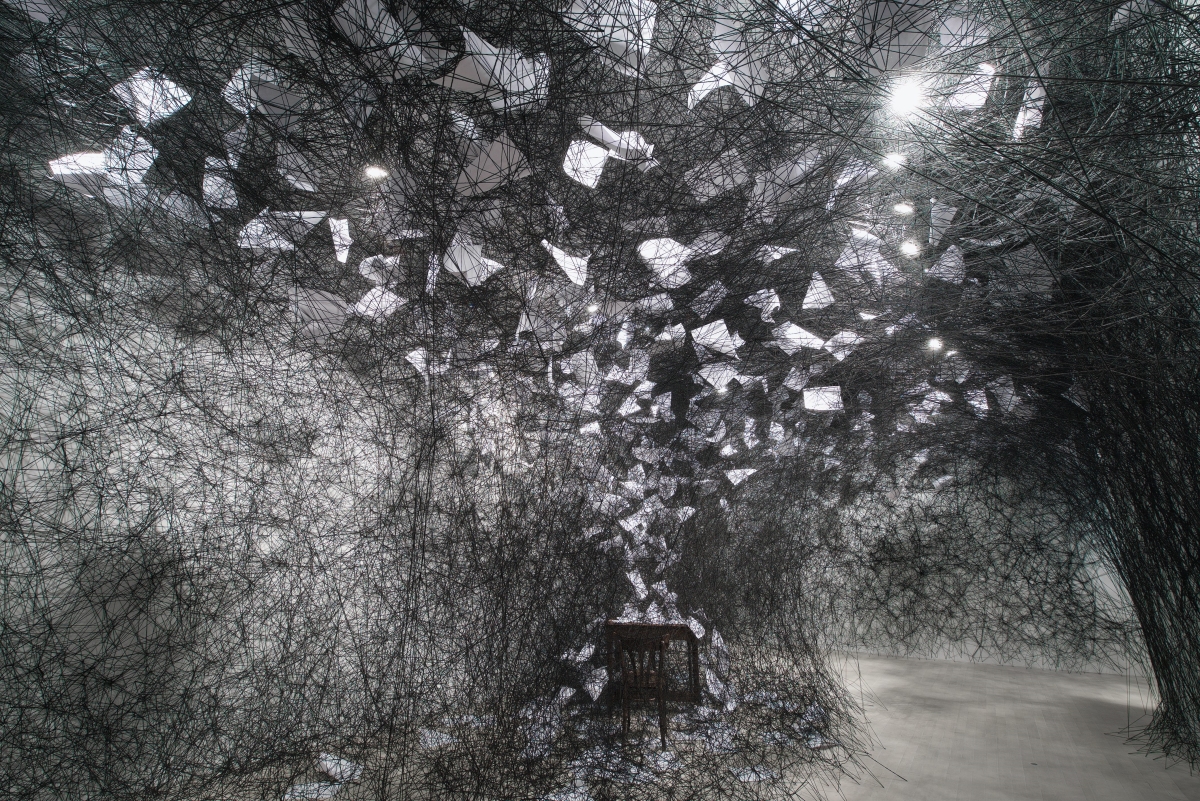

Installation: papers, desk, chair, black wool K21-Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany.

Ph Sunhi Mang. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

How are your life experiences reflected in your art?

When I was sick and particularly when I was diagnosed with cancer, my art changed. When I had chemotherapy, the medical system was very sterile and I felt detached from my body. I wondered where I was and where my soul was. I needed to explain more with my art. This sentiment has become present in my art.

Let’s talk about the creative process for your mega installations. How long does it take you to create these installations? How do you balance the human psyche and the physical space?

There are different kinds of installations and it normally takes two weeks with ten people. When I see the space, I first make a drawing with yarn. Every time it is different and the yarn is a mirror to different feelings. It is like human relationships—it can be tangled, lost, or cut off. I need to see the space first and start to think; it also depends on the venue. For Manifesta 14, the concept was that everyone has a story. I was collecting the story of everyone in Kosovo because history is so complicated. Everyone has different opinions on life, death, and love. I wanted to know more about

the people.

Your installations include old photographs. How do you select them? Do they have a particular meaning to you? What is the most important photograph that you remember?

I often go to the flea market in Berlin and I find old photographs from families—a lot of albums—so I feel I know this person, or owner of these photos. People kept these albums all their life and it was so important to see the past memory. When the person dies, it just becomes material and there is nobody anymore—but I see there is memory inside and I want to connect it through string.

Installation: old keys, old wooden doors, red wool. KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Yokohama, Japan.

Ph Masanobu Nishino. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: metal frames, red wool.

Melbourne Festival, Australia

Ph James Henry, courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

metal frame, red wool.

Installation view: Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.

Ph Sunhi Mang, Photo Courtesy: Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Your last show, Signs of Life at Galerie Templon, was a total success and people are still talking about it. Where have you shown since your return to New York?

I am very happy that the people wanted to see my work and even waited in line. I haven’t had a show in New York but I had exhibitions in recent years at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Jacksonville, The Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, and all over the world. And now, I also have an exhibition at the Hammer Museum in LA.

How can your work enter the viewer’s consciousness and persist through time?

People see my work and my installations but my installations are ephemeral. I have to cut the string, and I cannot keep the installation yet people remember the

experience for a long time. I don’t know why—maybe because they walk through it or they feel the same emotion.

Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, London, UK.

Ph Jeff Eden. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: mixed media.

Diskurs 2021-Ring 20.21, Festspielpark, Bayreuth.

Ph Sunhi Mang. Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

One of your most emblematic works, Dialogue with Absence (2010), is still being discussed. Do you think that women are really making progress towards equality?

When I lived in Japan, it was difficult as a woman and it was a man’s world. Then, I moved to Germany where my complex was gone and I felt like women were more equal. In Japan today, I still have the same feeling that the position of women is very low—there is still a lot to change. It has become better but not enough.

This question is like asking a parent to pick their favorite child, but do you have a favorite work? Which of your works do you consider the most relevant?

I cannot choose one, but my favorite exhibition was The Soul Trembles, which was held in 2019 at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. The exhibition traveled to Korea, Taiwan, China, Australia, and it is in Indonesia at the moment.

What are your lines to live by?

I like to have exhibitions. I cannot live without exhibitions. I live to make art.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

Installation: old keys, old wooden boats, red wool Japan Pavilion, 56th International Art Exhibition— La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy

Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: old wooden windows, chair

21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan

Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Installation: beds, bedding, telephones, photographs, water

Nizayama Forest Art Museum, Toyama, Japan Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *

Performance / Installation: hospital beds, bedding, black wool

Kunstmuseum Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023 and the artist *