Born in 1945 in Donaueschingen, Germany, Anselm Kiefer stands as one of the most significant and multifaceted artists of our time. His artistic practice spans an impressive range of media, including painting, sculpture, photography, woodcuts, artist’s books, installations, and architecture. Renowned for his profound exploration of history, mythology, and literature, Kiefer’s work delves into themes of memory, identity, and the human condition.

Kiefer studied law and Romance languages before pursuing fine art at academies in Freiburg and Karlsruhe. Early in his career, he engaged with Joseph Beuys, participating in the action Save the Woods (1971). His early works confronted Germany’s post-war identity, using parody and deconstruction to explore the Third Reich’s history and its impact on national consciousness.

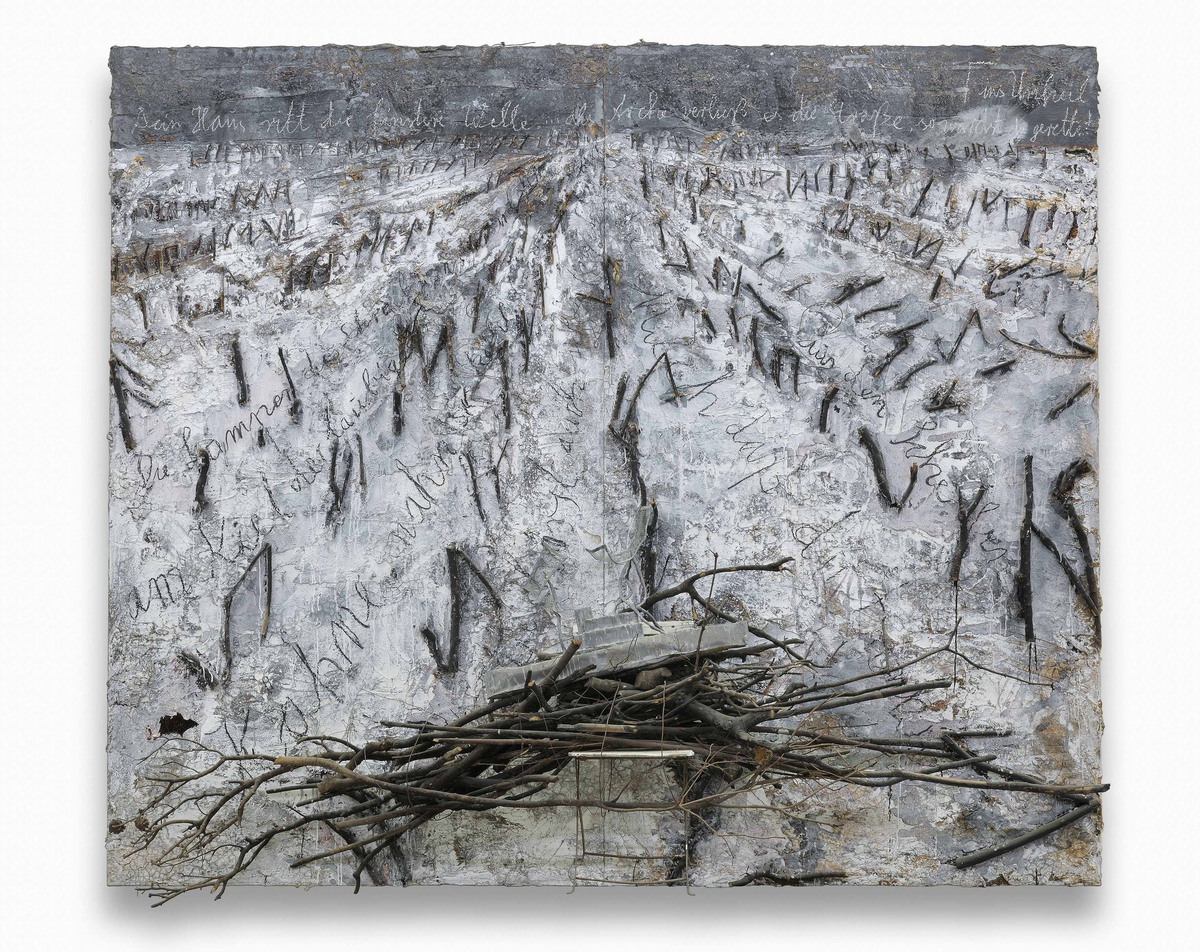

From 1971 to 1992, Kiefer worked in the Odenwald, Germany, where he began incorporating materials such as lead, straw, plants, and textiles—elements now emblematic of his practice. His work draws on a vast array of themes, from Wagner’s Ring Cycle and the poetry of Paul Celan to Biblical connotations and Jewish mysticism.

Kiefer’s innovative approach extends beyond traditional art forms. He transformed a former brick factory in Höpfingen into a studio, creating site-specific installations and sculptures. After moving to Barjac, France, he excavated the earth to build a network of underground tunnels and crypts, connecting numerous art installations. This studio-site is now part of the Eschaton-Anselm Kiefer Foundation, open to the public since 2022.

Kiefer’s oeuvre is a testament to his refusal of limits, both in scale and materiality, and in the depth of his exploration of memory and the past. His works are held in major museum collections worldwide and have been featured in hundreds of solo and group exhibitions. Notable exhibitions include Verbrennen, verholzen, versenken, versanden at the West German Pavilion, 39th Biennale di Venezia (1980), Heaven and Earth at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (2005), Anselm Kiefer, a retrospective at Centre Pompidou in Paris, and most recently, Fallen Angels at Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi.

Through his monumental body of work, Anselm Kiefer continues to offer profound introspection into the human condition, weaving complex connections between the past, present, and future. His boundless repertoire of imagery and media serves as a powerful testament to the sacred, the spiritual, and the infinite richness of the human experience.

An Interview with Anselm Kiefer

A Life Beyond Boundaries

Exploring the multifaceted journey of the renowned artist from post-war Germany to global acclaim

By Carol Real

Your early career was marked by a move from Germany to France. How did this change of environment influence your artistic evolution?

In Barjac I created pavilions, sorts of houses that are like a skin around a painting or a sculpture, which need their own site of action. I also created roads and lakes, drilled tunnels, and planted trees and vegetation. I planted sunflowers and tulips for use in my works. However, I’ve never painted a picture with the landscape of Barjac as the subject.

Can you elaborate on the significance of La Ribaute, your studio estate in Barjac, France, and how it has evolved over the years to become a focal point of your artistic practice?

La Ribaute was my first studio in France; I moved to Barjac in 1992. When I first settled there, everything I produced on the site was drawn from materials I brought from Germany, including photographs, books, lead. La Ribaute, like my other studios, was a sort of laboratory—a place for experimentation. The site also supplied a substantial amount of materials for my work. The numerous pavilions were conceived to provide access to the artworks within an ideal context, and each is part of an ensemble whose elements are connected.

How do the barren landscapes frequently depicted in your work reflect your artistic vocabulary?

There is no such thing as an innocent landscape. So much has happened in landscapes—they are charged with history, events, and battles, all of which leave traces. I sometimes give color to landscapes by using a torch, and then the color of the forest comes back to me. It’s a circular process.

Your fascination with celestial themes, such as the cosmos and stars, is evident in your art. Can you elaborate on the cosmic symbolism in your work?

The cosmos has always interested me—especially the link between the microcosm and the macrocosm. The pictures that I dedicated to Robert Fludd, with sunflower seeds, relate to this. Fludd said every plant on Earth has its corresponding star in the sky. In art and literature, there is always the overlapping of times.

Could you provide more insight into the importance of unconventional materials like lead and straw in your artwork?

Materials such as lead and straw are not objects that only come to life through ideas. They already have this spirit within them, which I discover and filter out. This happened with my discovery of lead. In my studio in Hornbach, the sewerage system was broken. When the plumber replaced the lead pipes with a more flexible material, I became fascinated by the dull shine of the lead and its flexibility. I then started to make sculptures with the material. Later, I recognized that my fascination with it was also due to its connection to alchemy.

The concept of ruins appears frequently in your work. How do you view the idea of “ruin” as a metaphor in your art?

As a child in Germany, I used to play with the debris from bomb ruins. Ruins are also a familiar motif in Romantic art. Ruins show traces of civilizations, battles…of history. For me, ruins are not the end but the beginning of something new.

In your early career, you explored themes of alchemy and mysticism. How have these interests evolved in your recent work?

I’ve said before that the alchemy of transforming the object into art is the true magic. Alchemy teaches transmutation—it is a physical and spiritual movement. While people imagine that alchemists try to turn lead into gold, it is actually that they picture themselves being transformed on another level. Of course, I have worked a lot with these alchemical materials—lead especially, although more recently I have been incorporating gold leaf into my paintings.

Since childhood, I had studied the Old Testament but as a young man, I read Jewish mysticism. The Kabbalistic tradition is a paradox of logic and mystical belief…for me, it’s a spiritual journey anchored by images. This interest in mysticism is also very present in my work. In Barjac, for example, the Die Himmelspaläste (The Heavenly Palaces) towers refer to Jewish mysticism, Merkabah. It’s the story of men who go through seven palaces. First, the feet burn, then the hands, and at the very end, just the spirit remains.

Given the diverse range of cultural, literary, and philosophical references in your work, could you elaborate on some specific influences evident in the pieces showcased in the “Fallen Angels” exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi?

There are several themes in this exhibition. Two works especially refer to philosophy—La Scuola di Atene (The School of Athens)and Vor Sokrates (Before Socrates). The pre-Socratic philosophers captivated my interest during my educational journey. Anaximander’s perspective, Anaximenes’ theory, and Democritus’ foundational understanding of atoms fascinated me as they sought to articulate the workings of the world.

Then Engelssturz (Fall of the Angel) and Lucifer touch upon the “fall of the angel”—for Christians, it signifies both the beginning of the world and the emergence of Evil. For many years I’ve been interested in the difference between this Christian perspective and the Jewish one in which, according to sixteenth-century Jewish mystic and theologian Isaac Luria, God receded, creating a space for freedom, and the world formed itself. This perspective seems more astute. God bestowed grace upon the world, which the world rejected.

In the final room of the exhibition are the “Besetzungen” (“Occupations”) works, which are based on an action that I did in 1969, in which I wore my father’s Wehrmacht uniform and mockingly made the Nazi salute in various European cities. These images were meant to incite thought and introspection. I pondered what actions I would have taken as a young man at the time.

All images courtesy of the artist and The Eschaton-Anselm Kiefer Foundation

Editor: Kristen Evangelista