There’s a peculiar stillness at the heart of Glenn Brown’s paintings—an eerie, swirling quiet that both beckons and unsettles. Known for his meticulous transformations of art historical imagery, Brown has long occupied a singular space in contemporary painting. With a practice that spans painting, drawing, and sculpture, he mines the visual languages of centuries past—Dürer, Rembrandt, Dalí, Fragonard—and reconfigures them into hauntingly beautiful hybrids that hover between homage and mutation.

Born in Northumberland in 1966 and trained at Goldsmiths during the fertile crucible of British art’s 1990s boom, Brown came of age with the appropriation artists of New York in his peripheral vision, but always with one hand stretched back toward the Old Masters. His thin, gestural brushwork mimics thick impasto, creating surfaces that defy their own flatness, while his sculptures—grotesque accumulations of oil paint and baroque references—offer a tactile counterpoint to the visual illusionism of his canvases. In recent years, drawing has become an increasingly central part of his practice, allowing him to disassemble and rethread the very fibers of pictorial memory.

Brown’s work has been exhibited in museums across Europe and North America, including the Serpentine Gallery, Tate Liverpool, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, and the Louvre. In 2022, he inaugurated The Brown Collection in London, not only as a permanent home for his work, but as a curatorial project in dialogue with both the present and the past.

In this conversation, Brown reflects on the logic of appropriation, the emotional architecture of composition, and what it means to make physical objects in a digitally saturated world. He speaks with clarity, complexity, and a profound sense of curiosity—an artist who paints not only with color, but with time itself.

An Interview with Glenn Brown

By Carol Real

Your approach to art involves transforming appropriated images through changes in color, position, and size. How do you decide which images to work with, and what criteria guide your choices?

When I look at different artists’ work, I’m drawn to something that feels incomplete—something I can project onto or connect with. Often, I bring together two very different works that make sense to me structurally, in a way that echoes the composition of the drawing or painting and responds to similar questions. There always has to be room for me to add my voice to the work. What’s most important is that I end up with a painting or drawing that has a strong sense of composition and moves your eye around in an interesting way. I will be looking for artworks to appropriate that I can recreate the structure of how your eye moves around the surface. Sometimes that’s turning it upside down, back to front, or completely re-engineering it. I want the composition to be very strong.

Can you share some specific art historical references that have had a profound impact on your work?

One of the first artistic movements that captivated me was the New York appropriation scene of the 1980s and 1990s. Artists like Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger, and Jeff Koons were taking found images and objects and repurposing them. I thought that was incredibly engaging—especially Levine’s work—because of this strange distance between the object you were looking at and the original object. I became fascinated by this lost space between two different areas of art history, very often.

Then I think Salvador Dalí changed my work when I looked closely at his paintings and drawings. I realized that sense of detail and crispness, and the entertaining delicacy in his work, was something I needed to add to my own.

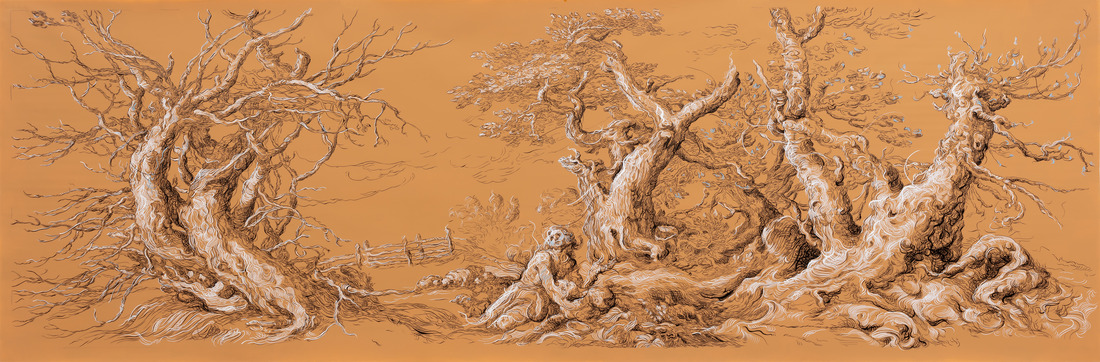

Later on, in the past ten years, I’ve become rather obsessed with Mannerist art, which fundamentally is art that takes the human form or the landscape and alters or changes it. It’s not about the way an object looks—it’s more about the way an object or body feels and what it’s like to inhabit the body, more than it is to look at the body. Things become quite distorted. Trees can become very gnarled and almost human, and the figure can become almost like a tree in its elongated form and elegant twists and turns.

Your work has been featured in numerous solo exhibitions worldwide. Is there a particular exhibition that stands out to you as a pivotal moment in your career?

In 2004, my show at the Serpentine Gallery in London marked a turning point—it made me realize I had a history and that my work had evolved. Though I was still a young artist, it gave me a sense of excitement about how much my practice could continue to grow.

Fundamentally, when I make most exhibitions for the commercial galleries, I want to create an exhibition that feels quite holistic, where the works communicate with each other. So the rooms within the exhibition can have particular themes, and the works can have conversations with each other depending on the combinations you put together.

Also, the city where the exhibition takes place—whether I’m showing in New York or Berlin or London—changes my attitude toward what I’m trying to communicate. I certainly try to make an exhibition that I think makes sense in a specific city.

More recently, having the Brown Collection in London is a sort of continually running exhibition and curatorial environment, which has again radically changed my idea of what it is to be an artist, because I’ve turned myself into a curator and collector. It’s made everything much more complex, richer, and more entertaining, I hope.

Your paintings create the illusion of thick impasto with thin, swirling brushstrokes. Can you describe the technical challenges and innovations behind achieving this effect?

My trompe l’oeil paintings are paintings of other artists’ very thick, gestural brushstrokes that I render very flatly. It was fundamentally a conceptual act of making a painting by making photorealist paintings of these three-dimensional surfaces. It is a very time-consuming process using tiny brushes and thin layers of paint. The extraordinary labour involved is absolutely the point of the paintings.

Over time, that’s evolved. I’m now much more inventive, and the process of making a painting is less conceptual and more about composition, color, line, and form. So now I have to imagine and create far more. The technical challenge of that is trying to sculpt almost an imaginary object. By sculpting, I mean representing something on a flat surface that looks three-dimensional. That fundamentally involves imagining a light source coming from a particular direction—or sometimes two or three light sources—reflecting on the surface of this object I’m trying to sculpt within the painting. My creative process is not like a three-dimensional computer rendering as it is all about applying paint by hand. The process of me painting becomes an important part of the way people read the image.

It all becomes an imaginary play of this three-dimensional world that exists on the far side of the picture plane. I find that much more interesting now than the more conceptual, dry attitude I had when I started in the 1990s.

In an age of digital art and rapid technological advancements, how do you see the role of traditional painting and sculpture in the contemporary art landscape?

As an artist who makes physical objects that are exhibited in gallery spaces, either hanging on the wall or on a plinth — I am aware that the viewer has a body and they move in a three-dimensional space. They move around the object, so every detail of the surface, size and colour is important. A work has a different emotional resonance from a distance than it does close up.

When I’m making a painting or a sculpture, I’m very aware of my own body and its difference from others. The length of my arm, the way my muscles work, and the gestures of my hand are all unique from how another person’s arm might move

That all connects to my brain, which again is another complex organism that creates a sense of movement and interplay. When my hand creates gestures, they are very different from the way a computer would generate gestures, because there are so many complex narratives at work to construct that sense of movement in my arm.

That physical sensation of being in a gallery, looking at an object that someone else has physically made, is something that AI or computers have real difficulty replicating in an engaging way. As an artist, when you’re making a piece of work, you encounter accidents, and then you react to those accidents and try to correct them. The narrative that emerges in the making of the piece is so complex, so full of twists and turns, that it’s not logical. It’s always about trying to engage and disengage, to look at something from a different perspective.

It’s so complex that I think technology can’t do something as interesting or as entertaining as what the human body and the human brain can manage.

Can you discuss any artistic challenges or creative blocks you’ve encountered in your career and how you’ve overcome them?

When I was a student in 1992, I had a tutorial with the artist Michael Craig-Martin, and he asked me a series of questions about what I was making and why I was making appropriation paintings. I had difficulty answering quite a lot of them. For the first time in many years, I just had to stop painting to answer this fundamental question: why did I want to paint? What did painting mean to me personally? Why was I so determined not to be a sculptor or a photographer or a performance artist? What was it about painting that particularly energised me? And I couldn’t quite answer that. I think for about three months I didn’t make any work. I just thought, and looked at as many artists as I could think about and look at, to try and learn what other people had done when I felt they’d hit similar mental blocks. The result was my ‘science-fiction’ series of paintings.

Then in 2014, I stopped painting again and started drawing. At first, I thought I was just going to spend a day drawing, because I hadn’t done very much drawing over the previous 20 years. But after the first day, I realised this was interesting and difficult. I drew again the next day, and the day after that—and for three years, I didn’t make any paintings. I just drew.

And that did get me past, I think, a block I had in my work. So sometimes it feels that you do have to put a sudden stop to what you’re doing and say, “Right, I’m going to completely change the angle I’m looking at my work from and making it from,” just to enliven life.

You divide your time between London and Suffolk, two very different landscapes. How do those settings shape the way you work, or the kinds of images and ideas that surface in your art?

Since having a studio in Suffolk, which is very much in the middle of the countryside, I’ve had to change the way I think about being an artist. When I initially got my studio in Suffolk, I found it difficult to work there. I was so used to being in London, surrounded by people and noise and culture and museums and galleries—which seemed the natural habitat of an artist—that when I was thrown into the countryside, I felt as if there was no culture here. What did my work mean when I didn’t have a museum or gallery to put it in context?

And I still feel that art is a very urban activity. It’s about communication, and it’s about people—and you find them in cities. London is a great city to find an audience. So I fundamentally had to learn that when you are in your studio, whether in London or Suffolk, the same audience is there. I just carry them with me in my head. I almost isolate myself in the studio and think about where the work is going to end up, who might be looking at it, and engage with that audience in an imaginary conversation.

So in the end, it doesn’t matter whether I’m in the countryside or the city—the imaginary audience is still the same.

Your work has been described as a fusion of various time periods and pictorial conventions. How do you view your art in the context of broader cultural and historical narratives?

One of the nice things about looking at paintings and sculptures from the past is that it becomes a very good way of time travel. To understand what you’re looking at, you have to imagine yourself in the environment—not necessarily just what is depicted in the painting, but also what was going on in the artist’s life when they were making the work. Paintings are very often of imaginary places, even if they appear to be relatively real. So you are always thrown back to the artist making the work, and to how the world surrounding them was changing—the political events happening during their life, and the social and cultural forces that both constrained them and gave them certain freedoms.

So if I’m looking at an artist like Albrecht Dürer from the 16th century, then I have to understand that the 16th century had very particular constraints on how an artist could make work, and who the audience for that work was. And that’s fascinating, because it’s a very different world than it is now. We’ve changed so much—technology, politics, nearly everything is different from 16th-century Europe—but there are still fundamentally human qualities that never change.

And again, with an artist like Jean-Honoré Fragonard working in France in the 18th century, the oncoming French Revolution and the very bourgeois audience he was making paintings for created this bizarre dynamic tension in his work, which I think makes them absolutely fascinating. Even looking at an artist working in the mid-20th century like Ithell Colquhoun, for instance—who was a British surrealist—you realize she was making work as a reaction to the Second World War. The politics and sense of the world were very different from the early 21st century. That sense of escapism she was seeking, the desire to reconnect with nature after the horrors of war, which had destroyed so much of both nature and culture, created a spiritual dimension in her work that was shaped entirely by the period.

These three examples of artists are so different from each other, but they’re all human beings and all share a sense of love, hate, hunger, and sexuality—things that don’t change quite so much. I realize, as an artist working in the 21st century, that no matter what, you reflect the environment that surrounds you—you almost do it automatically. So even if I’m appropriating a work from the 16th, 18th, or early 20th century, I’m looking at it from a 21st-century perspective, and I enjoy the sense of difference that this new point of view creates.

What projects or artworks are you currently working on, and are there any upcoming exhibitions or collaborations you’re excited about?

There are two pieces of work I’m currently involved with that are quite involved and will take a long time to complete. One is a large mural painting that I’m going to create for a space in the Brown Collection in London, and it will probably take the next two or three years to make. It’s all based on drawings by the 17th-century artist Abraham Bloemaert. I’ve restructured, altered, and twisted these various drawings of trees to create a woodland scene that wraps around three walls of the room. They’re very large paintings, and I love the idea of creating this all-consuming environment. I want the painting to wrap around you, as if you could imagine yourself within this imaginary woodland scene. I suppose it’s me trying to make a very grand statement, but one that is deeply tied into my ideas of the environment and nature. I’m excited about it because of its connection to the idea of climate change and the broader politics of how we go forward as a species.

The other project I’m working on is a series of paintings for a shell grotto. We built a grotto—a room that is partially buried in the ground and entirely covered in seashells—and it will have three paintings on the walls. I’ve been working on this for quite some time. The idea is that there will be three oval paintings of overlaid or confused heads. They’re portraits, but like many of my paintings, they feature multiple faces and contorted eyes, noses, and mouths—they’re somewhat horrific and fantastical.

It has an underwater feel, because of the colors I’m using and the fluid marks I’m incorporating into the paintings. The shells themselves—when you look at them closely—can be quite grotesque and twisted, and the patterns and colors they contain are influencing the brushwork and palette I’m using in the paintings for the grotto.

Editor: Kristen Evangelista

All images courtesy of the artist and the Brown Collection.

Special thanks to Justina Kiskyte from The Brown Collection.

The Brown Collection is located in Marylebone, London. The museum is open to the public, free, four days a week. www.the-brown-

Glenn Brown upcoming show is at the Freud Museum, London. “Glenn Brown and Mathew Weir: The Sight of Something” from 4 June 2025 to 19 October 2025. https://www.freud.org.

Images from The Real Thing (Retrospective), Landesmuseum Hannover, Germany, 2023.