Santiago Calatrava, a maestro of architectural poetry, intertwines the disciplines of engineering and art to craft structures that defy convention and elevate the human spirit. Born on July 28, 1951, in the artistic crucible of Benimamet, near Valencia, Spain, Calatrava’s journey traverses continents and disciplines, weaving a narrative of innovation and inspiration.

Educated at the Polytechnic University of Valencia, Calatrava’s thirst for knowledge transcended boundaries, leading him to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, where he delved into the intricacies of civil engineering. It was here that his doctoral thesis, “On the Foldability of Space Frames,” heralded the dawn of a new era in architectural exploration.

Establishing his architectural atelier in Zurich in 1981, Calatrava’s visionary designs soon captured global attention. His oeuvre, characterized by sculptural bridges and buildings, seamlessly marries form and function, echoing the harmonious dance between humanity and nature.

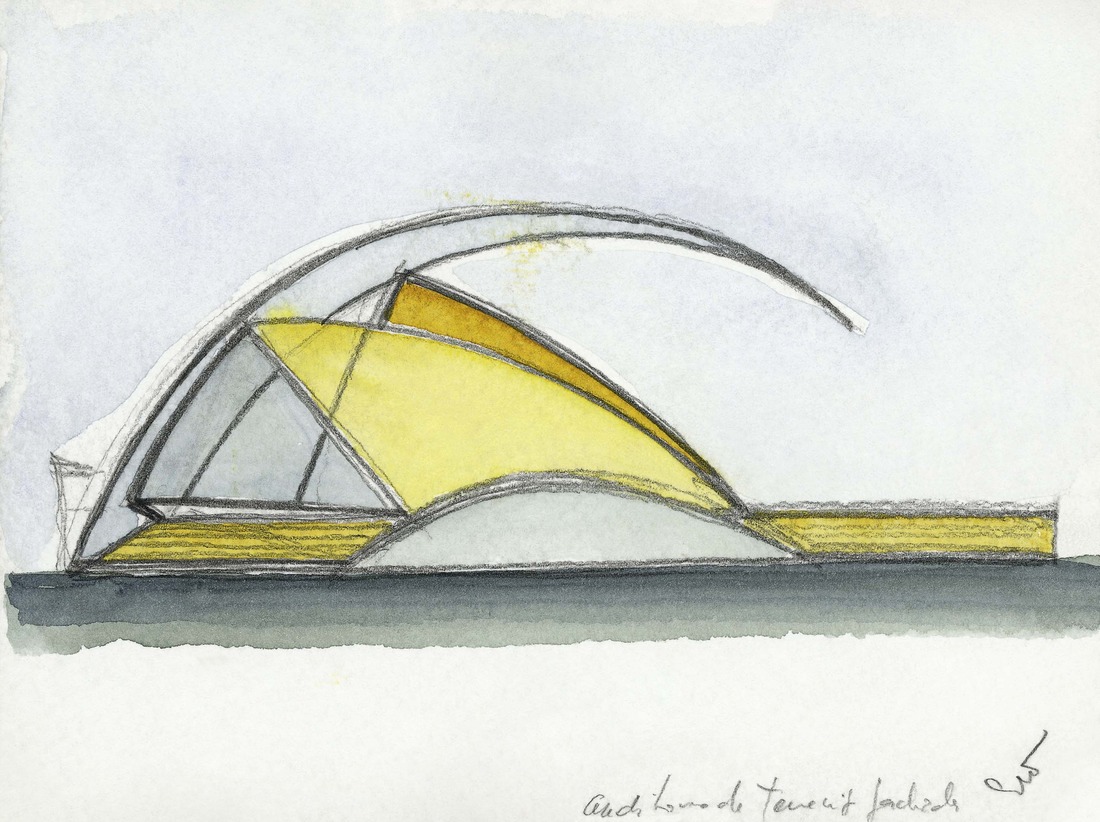

The nexus of artistry and engineering, Calatrava’s creations pulse with life, embodying the ethos of his multicultural upbringing. From the iconic Montjuïc Telecommunications Tower in Barcelona, a beacon of hope during the 1992 Olympic Games, to the ethereal Tenerife Auditorium, a testament to architectural splendor in the Canary Islands, each edifice whispers tales of innovation and ingenuity.

Embracing the fluidity of form, Calatrava’s designs transcend traditional paradigms, imbuing urban landscapes with a sense of wonder and whimsy. His magnum opus, the Turning Torso skyscraper in Malmö, Sweden, spirals heavenward, a testament to human aspiration and the limitless bounds of creativity.

Yet, Calatrava’s genius extends beyond the realm of architecture, manifesting in his sculptural endeavors that adorn cities around the globe. His works, showcased in prestigious institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, evoke a sense of wonder, inviting viewers to ponder the beauty of existence.

Recipient of the coveted Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects in 2005, Calatrava’s legacy transcends accolades, weaving a tapestry of innovation and inspiration that will endure for generations to come. As he continues to sculpt space and shape the skyline, Santiago Calatrava remains a beacon of creativity, illuminating the path towards a more vibrant and harmonious world.

An Interview with Santiago Calatrava

By Carol Real

Your initial plan to pursue sculpture eventually transitioned into a career path in architecture. How has your background in sculpture influenced your architectural designs, particularly in producing structures that resemble living organisms?

I went to Paris in the summer of 1968 intending to go to the École des Beaux-Arts, but due to the student revolt, the school was closed for two years. So, I returned to Valencia, my hometown, where I joined both the School of Fine Arts and the Polytechnic. I later discontinued my studies at the School of Art because, from the Polytechnic, I received a good combination of art and science. I moved into the study of architecture almost autodidactically. My formation in the field of art was particularly influenced by an admiration for sculpture, which I still maintain today.

How did your career and approach to large-scale architecture evolve after participating in the competition for Zurich’s new Stadelhofen Station, which marked your shift from small-scale projects to significant civic endeavors?

There are several aspects of this project I would like to highlight. First, it is a public building and facility accessible to everyone and an exciting opportunity to pursue professionally while serving the community.

On the other hand, it is a project closely intertwined with the city; beyond being a facility it features gardens, promenades, bridges, and entrances. The themes in this project became ongoing concerns in the rest of my work.

The belief in starting from zero after completing your doctorate is intriguing. How did this mindset influence your approach to architectural design and innovation?

I dedicated six years of my life to the purest study of architecture. Then, I spent five years studying civil engineering, which I concluded with a PhD including four years learning topology and pure geometric problems. This gave me time to think, reflect, and moderate the intensity of my architectural studies and its related doctrines. These almost 14 years of systematic preparation enabled me to start with a clear mind and a much stronger technical background.

How has your early passion for sculpture influenced your distinctive approach to architecture?

I read books by the great sculptor Auguste Rodin whom I admire, including L’ art: entretiens réunis par Paul Gsell (Art conversations with Paul Gsell) and Les Cathédrales de France (The Cathedrals of France). In the second book, there are two passages that I would like to emphasize.

Rodin said, “Sculpture is a particular case in the immense field of architecture.” Second, when describing architecture, he defines it as the plastic and harmonic play of volumes under the light. This became the canonical definition of architecture in the 20th century adopted by Le Corbusier, who quoted Rodin as saying, “Architecture is the harmonious play of volumes under the lights.”

Your bridge designs are renowned for their asymmetrical and dramatic structures. How do you balance the artistic elements of your designs with the engineering requirements of bridge construction?

The technique is the instrument of the poetic in architecture. This is where someone could metaphorically find a “lever” of beauty. Some buildings are related to their technical nature and bridges are among them. Bridges are symbolic, linking two sides that were not connected before. They have been essential parts of our cities and landscapes for centuries, as elements that are ornate and bring character. Think about what Paris would be like without its beautiful bridges.

From bridges to museums and public buildings, your portfolio is diverse. How do you approach the design process differently when working on different types of structures?

All categories, bridges, museums, auditoriums, and transportation facilities have something in common. They are public spaces and when an architect designs them, he works for the interest of the community. Buildings dedicated to the community have the potential to become landmarks. They qualify our cities, not only through the pure function that they represent but also through the value that they offer, making cities more livable and present in the minds of the inhabitants.

Think about most of the great capitals of the world and the importance of their bridges, museums, railway stations, or libraries. We realize then that a city is not only composed of streets, squares, and parks but is also made up of buildings that convert an area into a landmark, offering points of reference for both residents and visitors while enhancing its overall appearance.

Having designed over 50 bridges, your work has become synonymous with cutting-edge bridge design. How do you conceptualize and integrate the cultural and historical context of a location into your bridge designs, as seen in projects like the Bac de Roda Bridge in Barcelona?

When I started designing bridges, I realized that in the schools of engineering, “bridges” were a subject coming out of the post-war reconstruction period of cities and roads in Europe. They were considered a functional tool, ignoring their symbolic character. The reason was that in the 50s and 60s, there was a dramatic increase in the rebuilding of bridges that were destroyed in the war. This diminished the importance of creating landmarks, hindering the integration of their landscape into the design.

All my effort came from the facts given to me at that point. I had to work with technical resources like steel and concrete in a short and restrained economical framework, but at the same time, I was trying to exalt the bridge’s former symbolic character.

You’ve mentioned the importance of practicing architecture as a convergence of artistic fields. How do you integrate elements from different art forms into your architectural design?

There are two aspects I would like to highlight.

First, the ways in which artistry and craftsmanship impact the quality of architecture. When architecture attains a high level of quality and beauty, there comes a point where creativity and skill are in full bloom. This is evident in the Romanesque or Gothic cathedrals that were built centuries ago. We see that the craftsmanship as well as the technical and artistic aspects are essential to the inherent beauty of architecture.

Second, the fact that architecture is an art like sculpture or painting. Even in the most basic detail, the artistic essence breathes life into architecture, simultaneously offering users satisfaction beyond its utilitarian purpose.

Architecture and utility are deeply bonded. If it is a bridge, it should permit people to circulate. A station should have accessibility and provide the possibility of connecting regions and this produces spiritual satisfaction, which enriches the life of the site, which hosts thousands every day. Architecture should function and offer a social contribution.

How integral is it for you to uphold a relationship with painting and sculpture alongside your architectural endeavors?

When we examine the facade of Notre Dame in Paris, we observe that the architecture serves as a foundation for sculpture. The facade showcases the most magnificent symbolism depicting the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Kings of France. There, we are confronted by pure extraordinary sculptural work that is supported by architecture.

Visiting the Sistine Chapel, we recognize architecture’s role in supporting painting and at the same time Michelangelo used his art to paint elements that belong to architecture. If the figures that Michelangelo painted were extracted, we would discover that more than 50% of his paintings are painted architecture. Painted beams, capitals, arcs, and more accompany the whole scenery that he has created.

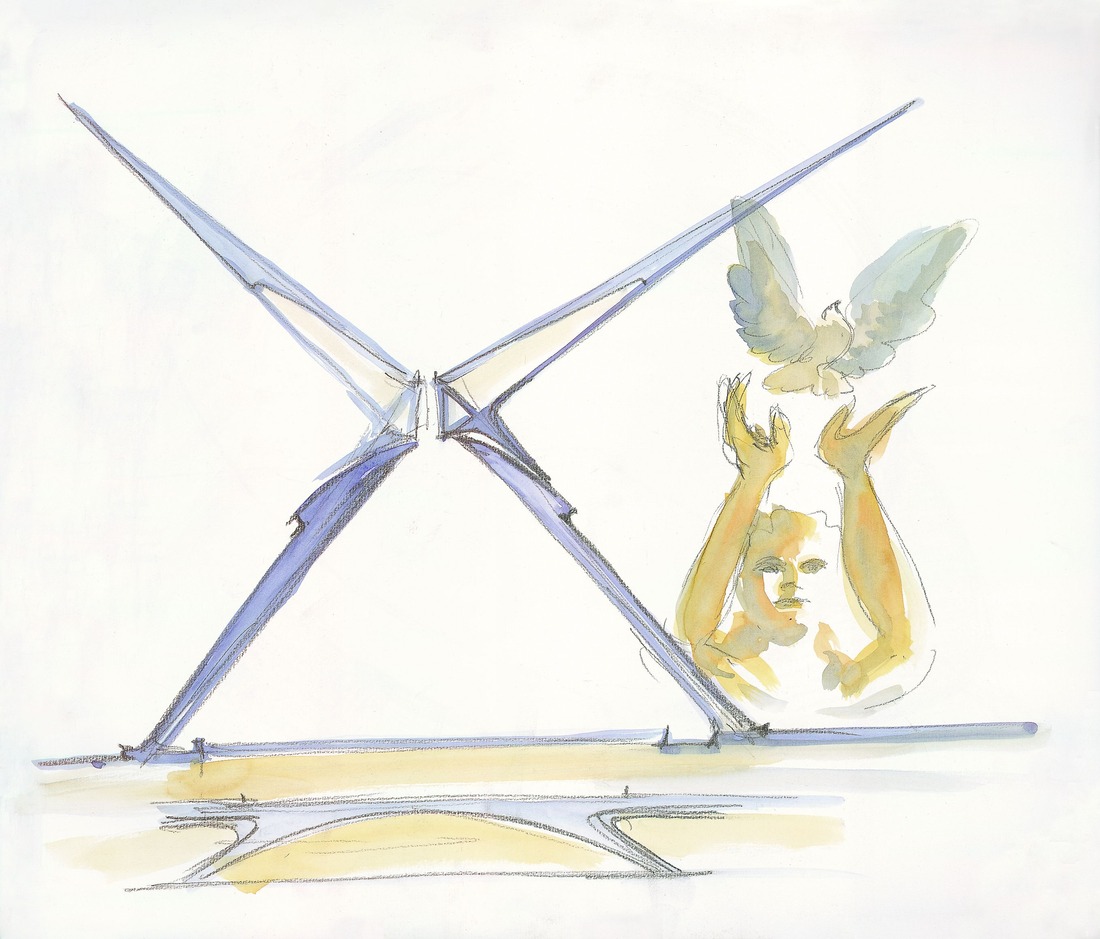

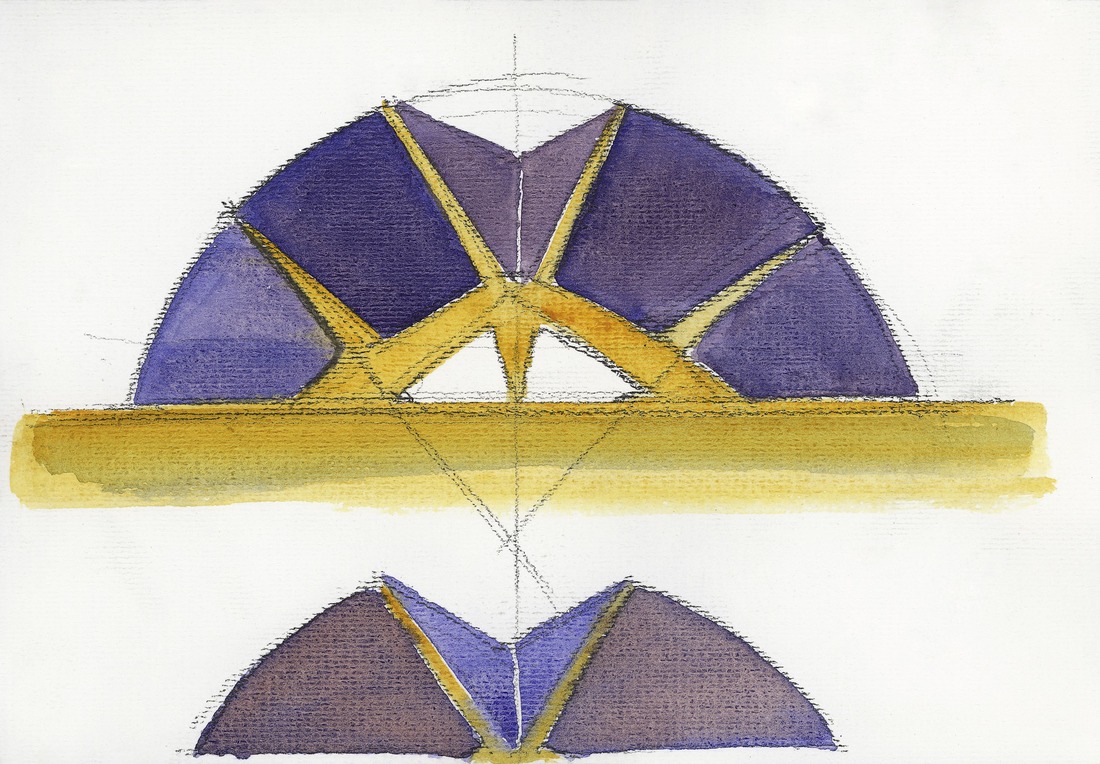

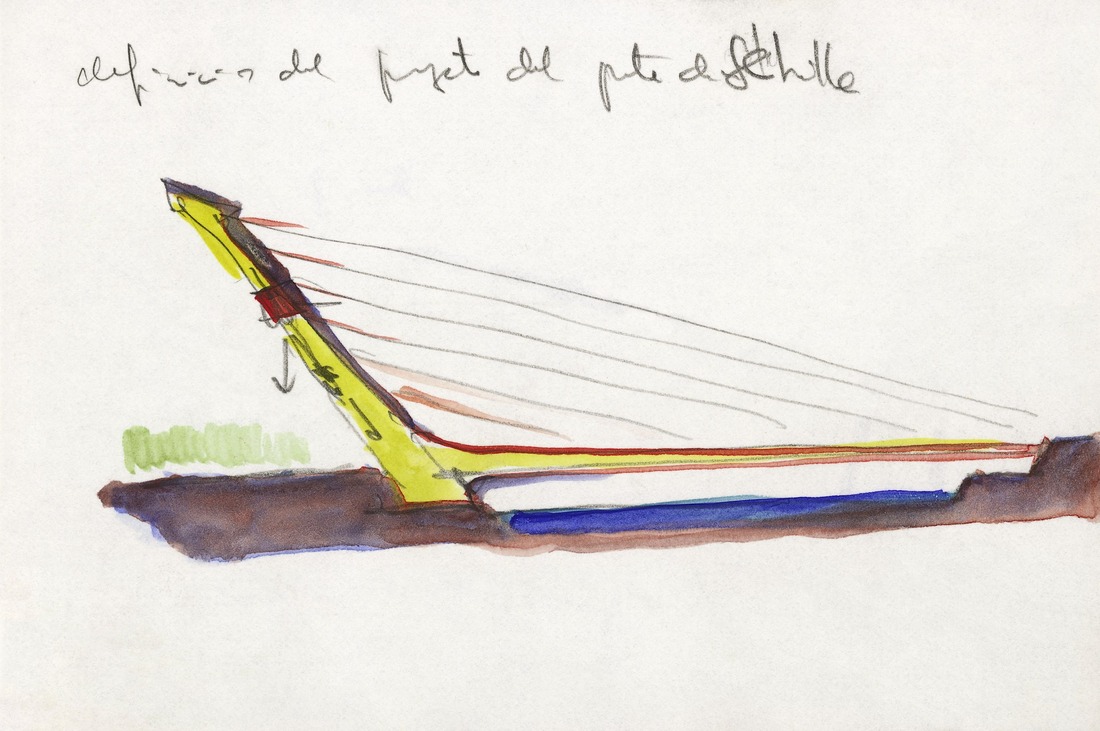

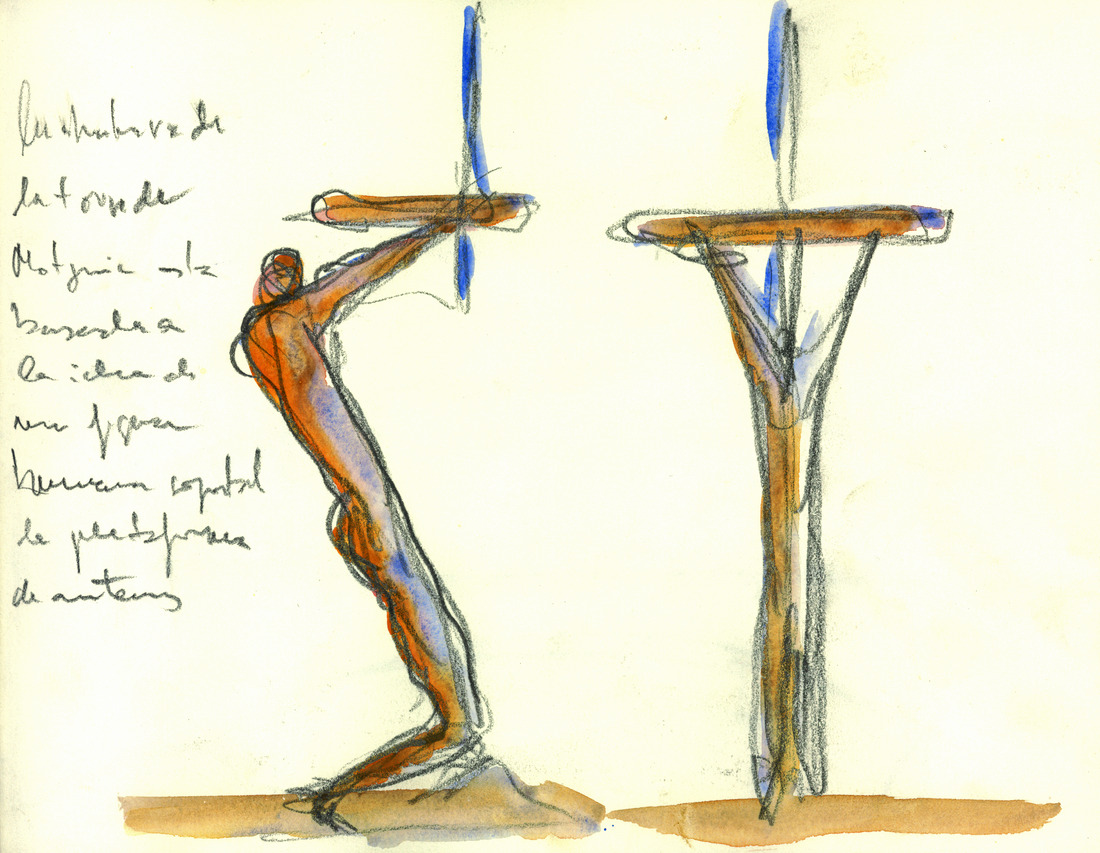

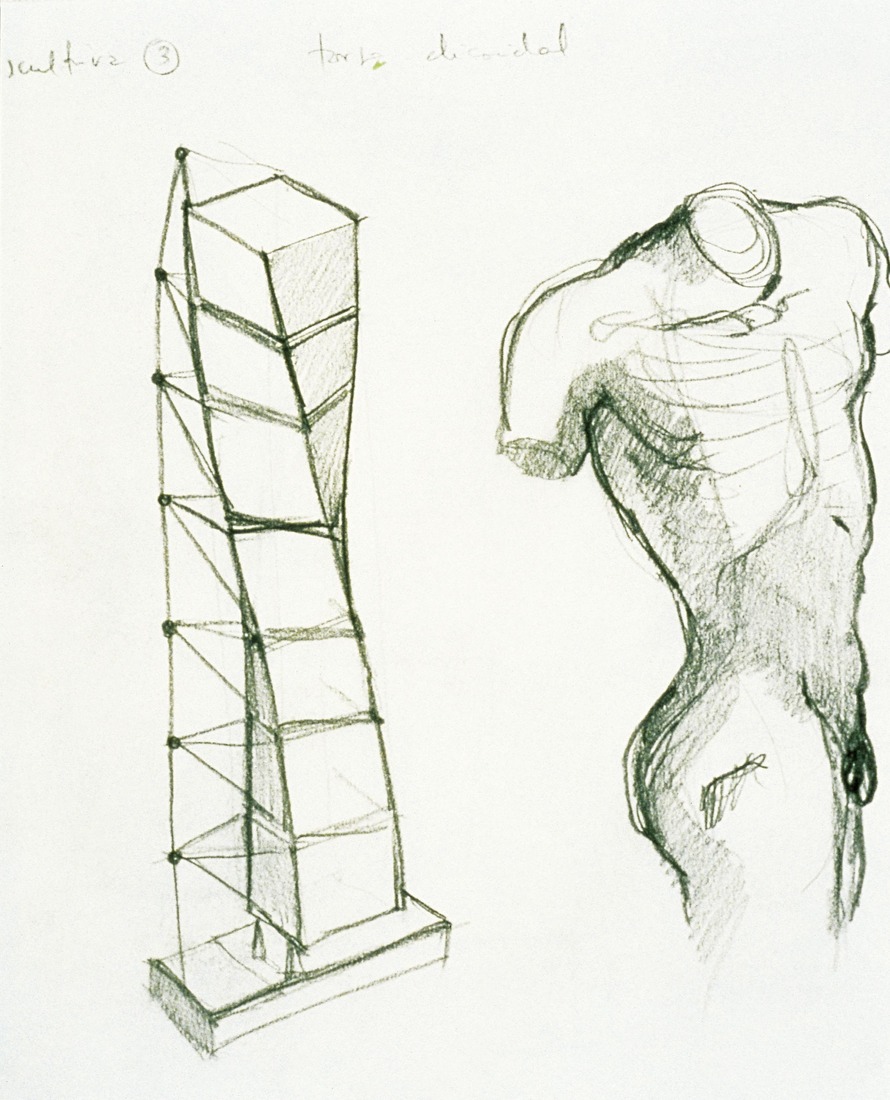

The integration and the interplay of culture, painting, and architecture are sometimes harmonious. They are living together. There are other situations in which we cannot observe this high level of symbiosis. I approach architecture always through sketches that I treat like paintings. I paint them, watercolor them, and regard them as if they were already one modest yet significant stride toward the final construction.

The sketch has an important status. It becomes a serial process through drawing and watercolor. I try to approach the final character of the building through an artistic gesture, to emphasize the artistic aspect of architecture as a final product.

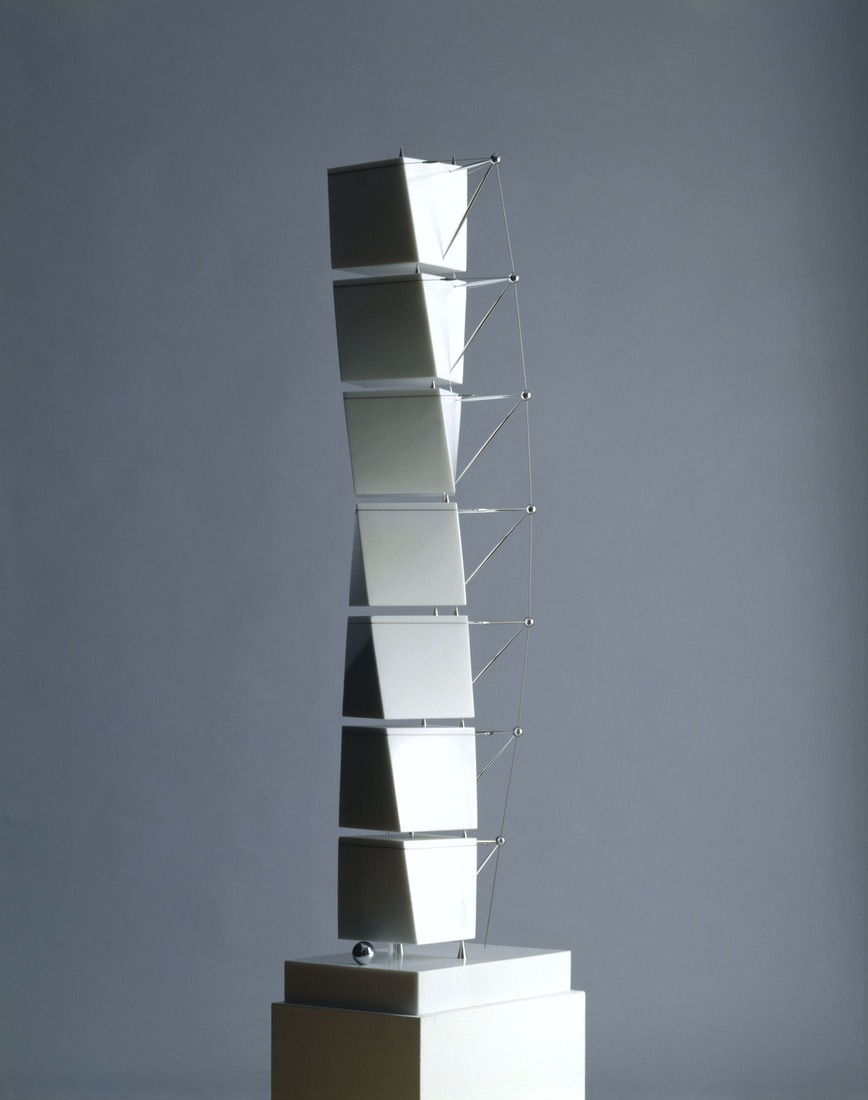

The same thing occurs when producing physical models. When creating models, I seek the highest quality. They represent miniature sculptures, offering numerous insights into a building, allowing me to analyze and evaluate the potential nature of a project.

In all cases, sketching, modeling, and working with my colleagues, becomes an homage to the concept that ultimately architecture is not only functional, but it’s also spiritual. When it is beautiful, it has the potential to become art.

What inspired you to incorporate dynamic and interactive elements into your architectural designs such as the Kuwait Pavilion for Expo ‘92?

Force is the product of mass and acceleration. Acceleration is a cinematic or kinetic value—a dynamic value—so that means that there is a latent movement in the force.

I dedicated almost four years to my PhD which explored the transformation of geometrical bodies from a rather complex three-dimensional element into one line. This drew my attention to nature, which is all about change, movement, and continuous transformation. It is like the flowers that close in the night and open during the day. I illustrated the introduction of my thesis, which was titled “Natura Mater et Magistra,” or “Nature, Mother, and Teacher,” by including photos of flowers in a sequence of transformation. I also realized that even the most solid examples of nature like the mountains or seas are transforming as well.

The notion of dwelling in a dynamic cosmos, amidst planets and stars, is deeply ingrained in our existence. We are, as well, constantly transforming and it seems that this concept is essential for humanity.

In buildings, apart from the experience of movable parts such as drawers, doors, canvases, curtains, etc., I introduce the beauty of buildings that open and close like a flower during the hours of the day such as the Pavilion of Kuwait. This idea has also been implemented in the Milwaukee Art Museum and Florida Polytechnic University. The idea of a building that “breathes” and can move throughout the day, is enormously exciting.

Nowadays we have at our disposal technologies that permit movement or transformation, enhancing the static character of buildings’ facades. For instance, hydraulic systems that guarantee safety and responsiveness to challenges such as smoke extraction, elevators, and so forth. I have tried to achieve this by incorporating hydraulic systems or integrating proprietary drives found in the construction market. I always endeavor to add value to architecture by adding transformable characteristics to buildings, so they are not presented as rigid and static elements but also can change.

In your pursuit of integrating movable features into your buildings, how do you envision the relationship between architectural form and dynamic functionality evolving in the future of urban structures?

If we look at big architectural achievements such as French Gothic cathedrals, the Burgos Cathedral or Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, we realize that for ages people tried to do something within the limit of their possibilities, and then finally made it. The achievements during that era parallel the aspirations of modern society, akin to today’s endeavors to explore the cosmos or reach Mars. So, we are no longer focusing on architecture to attain the most extraordinary achievements of our time, but if we look at the modern technologies that are being used for those accomplishments, we see many of the elements that can unfold, move, and change.

So, these high-end technologies that can provide abilities of transformation by changing shapes of things and structures made me very enthusiastic, revealing that at some point, architecture also follows this pattern.

I got inspired by the fact that we could achieve a distinctive symbolic quality by using functional elements, allowing for transformation and pushing the boundaries of rigid buildings. This is what I was aiming for and remains my dream even today.

Your projects often involve extensive study of the human body, nature, and various aspects of the environment. Could you elaborate on how these studies inform your design process and contribute to the unique and sculptural qualities of your buildings and bridges?

Using the human body as a blueprint has always been my interest since childhood. My visit to the Greek ancient temple of Apollo in Delphi influenced me even more. I was confronted by an inscription, among hundreds, that read “Man is the measure of all things.” This diachronic expression conveys the fact that “we” are the measure of the environment that surrounds us and it defines our perception of dimensions.

By comparison, we appear small next to a mountain. We consistently gauge relationships, relying on our senses to perceive our relative position. We could revisit the Renaissance era and Michelangelo’s assertion, “L’architettura dipende dalle membra dell’uomo” (Architecture depends on the limbs of man). We realize that the height of a chair or a table, the width and height of a door, the height of a ceiling, the feeling of space, and the transition from one space to another, are related to human measure.

Can you discuss how you explore the idea of the arc in your bridges?

In the case of bridges, even though I came from a traditional vocabulary, I tried to revitalize the idea of the arc. Questions had occurred to me, like using the torsional stiffness that box girders have, and they were not much in use. I tried to take advantage of this and experimented. So, sometimes I allocated the arc in the center of the bridge, or put it aside, trying to emphasize the direction of a stream, orientation towards the sun, or even the position within the city, creating tension between the shape of the bridge and the surroundings. This creates a vocabulary through the potency of technical expertise and the appropriate use of static values.

However, I think we can go much further, so that the bridge can create other aspects of beauty, by providing monumental pieces of art like sculptures. For example, the Pont Alexandre III in Paris is a major work that combines technique and art, highlighting how important a bridge can be for the identity of a city.

Bilbao Airport is nicknamed “The Dove.” How does the symbolism of your architectural designs contribute to the overall narrative or identity of a space?

It is interesting to develop a concept from an allegorical idea, like a building that could be “light” as a dove, or “flies like a dove.” This transcends the fact that it’s a stable structure, creating a surreal world of imagination. Symbolism in architecture is a very interesting field, exactly like in painting, and becomes a source of inspiration.

We designed the UAE Pavilion for Expo 2020, which many people likened to a falcon with movable wings.

As a result, a relationship between buildings and the public emerged. A metaphorical aspect led people to create associations and experience the building in a more intimate and personal way.

The Auditorium de Tenerife in the Canary Islands has a distinctive form resembling a breaking wave. How do you balance functionality and symbolism in your designs for cultural and artistic spaces?

The Auditorium in Tenerife is surrounded by a beautiful landscape, situated almost on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. This building is one of the most sculptural buildings that I have ever designed. It appears to be an enormous white sculpture against a backdrop of blue ocean and sky. However, I would like to add that the Auditorium, as well as the Recinto Ferial de Tenerife (the Convention center that was built in the old oil refinery area) and the Palmetum, were built in a very poor area of the city of Tenerife. The Palmetum was built on a hill that was created from waste which was collected there for years. This hill was covered and formed with reinforcement and various technical processes, and today it is a great palm park. We managed to create this trilogy over a period of 10 years. This part of Tenerife has completely changed and now is one of the most liveable and desirable areas of the city.

The Gare de Lyon Saint-Exupéry in Lyon is a monumental structure. How do you ensure that large-scale transportation hubs like this one seamlessly integrate into their surroundings while making a bold architectural statement?

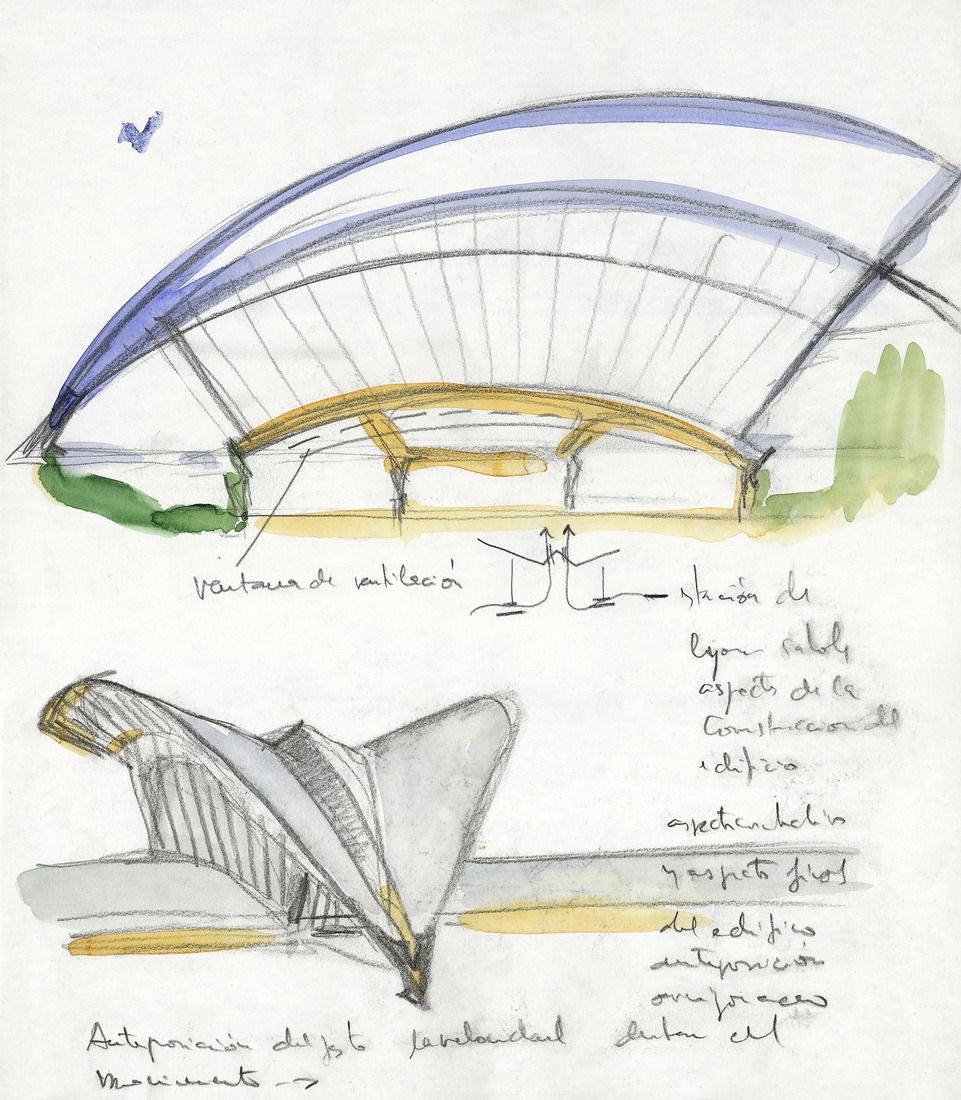

After Stadelhofen Station, Gare de Lyon was another seminal experience and it reflects two things.

On one hand, the arrival of high-speed trains in Europe was entirely new at the time. The French Railway (SNCF) and the French government created the infrastructure and high-speed train lines (TGV), which today is one of the largest transportation systems in Europe. I emphasize this because the Gare de Lyon Saint Saint-Exupéry was the first pure high-speed railway station in Europe, and it was a huge honor and a great experience to be a part of it.

On the other hand, since it was partially financed by the region, certain criteria were fulfilled. Being close to the airport we sought to create a kind of gateway. So, we decided to make a monumental gesture, creating it among the green fields and countryside of Satolas, where the sculptural form of the building would arise, signaling the airport and the station.

This was one of the most satisfying technical and professional experiences I have had.

When designing the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, how do you ensure a cohesive architectural complex with diverse structures serving different purposes?

This large-scale structure of the City of Arts and Science proves that during the life of an architect, one can be engaged in projects that span more than 25 years and a project of a cultural interest differs from others.

The City of Arts and Science is a cultural project that includes an auditorium, a planetarium, a science museum, an exhibition hall, a conservatorium, an arboretum, and various areas where artists can exhibit their work.

The City of Arts and Science shows the force of culture when transforming areas. Usually, we could think of making a cultural investment in the heart of a city. However, in this case, the idea was similar to the projects in Tenerife, where the authorities were clever enough to make a subversion and a significant cultural investment in an economically disadvantaged area.

By adding the City of Arts and Science to the urban environment, Valencia was completely transformed. The project offered an opportunity to complement the perception that everyone had of Valencia. Regional community schools use the buildings for science events and exhibitions. Significant interaction has emerged between people and the various buildings, making this complex one of the most frequented public facilities in Spain.

Since I was born in Valencia, it makes me extremely happy and proud that my beloved city acquired a new identity through music, science, education, etc.

It also showcases a harmonious blend of art, science, and architecture. How do you believe this synthesis contributes to a city’s cultural identity, and what role do you see such multifaceted structures playing in urban development globally?

Many of my projects in Spain appear in a particular period. My country had suffered a dictatorship for many years. Suddenly, Spain and Spanish society were illuminated by the sun of democracy, which rose in full power after the dark period of dictatorship.

Democracy brought an enormous wave of enthusiasm and joy to the country, and I was honored to participate in this new period of freedom that was delivered to the heart of the people.

Effectively, buildings like the City of the Arts and Science, the projects in Tenerife, and the bridges in Seville, Barcelona, and Bilbao, make me feel so proud of my contribution because I belong to the generation that was born in a dictatorship and even in my case left the country. What’s truly remarkable is its reflection of immense enthusiasm for culture, science, education, engagement, and openness. All these characteristics are embodied in the new period of Spain, which I was honored to be part of.

The Bac de Roda Bridge was your first internationally recognized project. How did the design of this bridge set the tone for your subsequent works, and what challenges did you face during its realization?

What I mostly think about this bridge is the “collective” spirit of Barcelona and the tremendous enthusiasm during the years of urban transformation preceding the 1992 Olympics. This was cogently led by the municipality, restoring the damaged urban fabric, and completing unfinished projects.

An important aspect was establishing a connection above the trains, spanning a disadvantaged area of the city, achieved through the addition of this bridge as a symbolic element. The area was revitalized by the time the new East-West connection emerged in Barcelona.

I think we contributed by making a completely new intervention in areas that could be restructured and relinked with the rest of the city. The project contributed to not only a better neighborhood but also a better city.

How do you balance aesthetics and functionality when creating iconic structures like the Puente del Alamillo in Seville, which is known for its spectacular design and leaning pylon?

We are in the south of Spain; we are in Seville. Like all Andalusian cities, Seville has a specific magic. It is called “El Duende,” which is a type of magical spirit. No one could feel it unless visiting. For example, Seville in April, when the orange trees are in bloom, and walking in this fantastic temperature during the evening, smelling these perfumes… I don’t believe there is any city in the world that is so magical in this season. There are places with enormous architectural interest, such as the Palace of Alcazar with its beautiful gardens, and places in the heart of or near the city of Seville.

In terms of the Expo, it was necessary to be highly sophisticated and extremely clear in integrating the enchanting atmosphere of the city with Seville’s projection to the world as a 21st-century city.

What influence does the context of a site, such as the 1992 Olympics, have on your design decisions? The Montjuïc Communications Tower in Barcelona is often described as sculptural.

Montjuïc is a sacred mountain in Barcelona. It occupies a special location surrounded by the city and at the same time faces the sea. When I was commissioned to design this Olympic tower, I envisioned a figure with extended arms holding a ring symbolizing communication and openness to the world. In addition, as a part of the Olympic Park, this anthropomorphic form depicts the figures of the athletes who were competing directly underneath it.

The Turning Torso in Malmö, Sweden is your first skyscraper. How did the challenge of designing a twisting skyscraper differ from your previous projects, and what inspired this unique form?

All my life I have been pursuing formal research through drawings, paintings, and sculptures. I am constantly working by developing shapes and forms without knowing when or if they will be used or adapted to architecture. This has permitted me to establish a personal vocabulary. So, I was creating sculptures and studying the behavior of the human body by observing the way we stand up and the importance of our vertebral column. This led me to various sculptures using simple shapes like cubes, cones, and spheres almost like Cubists. I was inspired by Cézanne’s statement: “Il faut traiter la nature par le cylindre, la sphère et le cône” (Capturing nature through the cube, cylinder, spheres, and cones).

The Turning Torso offered me the opportunity to transform these sculptural studies into a unique building by treating it as a real living organism. I added functionality and incorporated elevators, stairs, emergency stairs, etc. so that people could live comfortably while preserving the purity of the gesture.

It was finally possible to achieve this balance. Turning Torso is a landmark that highlights the site and at the same time is full of life, which makes architecture extraordinary. Eventually creating a piece of art by working like an artist on something that will be full of life, full of people, spending their life inside it, or even by looking at and interacting with it, makes it the ultimate example of architecture.

The Liège-Guillemins railway station features a lace-like roof that blurs the line between indoors and outdoors. How do natural light and transparency contribute to the visitor’s experience in transportation hubs?

Liege-Guillemins station was a step forward. Up to now, it was common for a station to have a facade that people would need to pass through to access the station. Almost every station works in this manner. For example, I thought that since many people were coming there by bus and needed some time to arrive and then take a high-speed train to go to Brussels in half an hour, the concept seemed to me to be more like a bus station or a bus shelter without so many formalities and barriers.

Thinking of a roof as shelter and the possibility of an open structure brought us to create a wide canopy to assemble people who approach the station easily without having to traverse the barrier of a facade. Technically, we went far beyond and achieved a vaulted structure of 185 meters span with two side canopies, 70 meters each free span. A train enters the main hall which is covered by the structure of arcs and the transparency creates an indoor-outdoor quality that welcomes people to the great city of Liege. As a result, instead of having a “closed building” we have a “welcoming gate” for visitors.

Incorporating kinetic elements, such as the movable sunscreen in the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Quadracci Pavilion, enhances the overall experience of a space. What challenges arise from these features?

In the case of the Milwaukee Art Museum, I was examining the idea that a museum should fulfill its role of showcasing its collection while also having the capacity to display significant works of art, supported by all necessary functions. I’m very grateful to the project authorities because it was the first museum that I designed, and through their guidance, we achieved a functional structure that satisfied their needs.

Apart from that, the Milwaukee Art Museum has an exceptional location. It is situated at the end of Wisconsin Avenue, where the War Memorial Center designed by Eliel and Eero Saarinen is at the end of the parallel Michigan Avenue. Therefore, I aimed to imbue this place with the character of a pavilion, drawing inspiration from the end of Michigan Avenue. By doing this, I introduced a bridge to bring people in, and then also a roof that has a sculptural quality and an extraordinary position facing Lake Michigan, which is truly like an ocean. The unique technology of the brise soleil (sunscreen), which opens with the changing position of the sun during the day, controls light in the main hall. During the day, this movable element functions by a simple hydraulic system that makes it open and close. Through the significance of this gesture, the museum’s connection with its unique roof has become an icon.

To summarize, the museum is a combination of a functional tool and simultaneously a highly symbolic element connected to the city. Recognizing the importance of Wisconsin Avenue’s aix, and then further acknowledging the importance of the expansive landscape before it through the ecumenical gesture of the museum’s “opening” wings, is appreciated by the visitors and serves as a tribute to the community.

In what ways do your extensive studies of the human body, nature, and various aspects of the environment influence the aesthetic and functional aspects of your architectural designs?

Today it’s impossible to avoid environmental questions. It’s part of our duty to build with the proper materials, to think about the material qualities of the elements we are using and to understand the possibility of recycling and minimizing the carbon footprint. On the other hand, I would like to underline another aspect of the importance of the environmental impact. Nothing is more damaging to our environment than bad architecture. It damages our physical and spiritual environment, making us poorer.

This is probably the reason why buildings that were built in a hard period of functionalism, and sometimes due to social factors, today are inhabitable. People need beauty and harmony and need to see a reflection of themselves in their living environment. A very good example of this is the vernacular architecture throughout the Mediterranean. For example, on the Greek island of Santorini, even in modest conditions, people lived in concordance with nature, building homes that from our current perspective are marvels of beauty and harmony, perfectly suited to their needs. The idea of humanizing our architecture is important. The notion of “feeding” ourselves with quality and “well-presented food,” literally and metaphorically, could also be a spiritual procedure.

This is the reason to think about the human body. Considering the “individual” and their connection with the interior and exterior of the buildings, the harmonious proportions with the environment, how one interacts and moves in response to the buildings and urban elements.

Your work often draws inspiration from nature, human anatomy, and various aspects of the environment. How do these influences shape your design process, and how do you foresee architects incorporating a deeper connection to nature in their future projects?

There are different ways to understand the relationship between nature and architecture. (There is even a science called Bionics which is about the application of biological methods and systems found in nature to the study and design of engineering systems and modern technology). It uses highly advanced materials, concrete, steel, carbon fiber, or even wood etc.

We should understand that nature is our mother and our teacher. We need to take care of our mother nature. We need to understand that by building, we are intervening in nature, and we should do this with harmony.

By listening to Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy for piano, chorus and orchestra, the chorus sings “in the temple of nature.” So, we must go far beyond. We should admire nature in a sacred way. We should admire the magic of the mountains, the seas, the waves, the dunes in the desert, the forests, the beauty of the animals, and the trees.

It’s so important to educate the young generation in that regard. They should understand that nature is not only a gift but also the most evident representation of the deity. It is something admirable, something that needs to be preserved and venerated.

How do you define yourself as a person and an architect?

I want to underline the three virtues of architecture that are eternal and define me as a person and architect. First comes utility, second firmness, and third beauty.

If we could connect architectural identity with an individual’s personality, we would notice that the pursuit of utility in architecture relates to the kindness of a person. Firmness in architecture relates to the tenacity of a person, and beauty in architecture relates to the intelligence of a person.

Without utility, architecture lacks a function. Without firmness, there is no stability. Without beauty, there is no spirit in architecture.

Why does kindness matter?

An architect should prioritize utility in their work out of affection for people. Architects should make doors, chairs, stairs etc. properly because they love people.

There is an important aspect embedded in functionality, which makes it the secret of philanthropy and altruism in architecture.

Why tenacity? Because, even if we need to persevere in every discipline in life, particularly in the field of architecture, insisting on our goals is very important.

The necessity arises for every member of a project to invest thousands of working hours, requiring the architect to effectively manage and coordinate the entire endeavor with determination and efficiency.

Finally, beauty. Why link beauty with intelligence? Because in architecture, strict accuracy is needed to determine the atmosphere, develop the vision, and deliver the intended message.

Insisting on detail and proportions, finding a balance between shadow and light, and putting all of them into a harmonic dialogue, the result is the sense of intelligence that generates beauty.

All images courtesy of Santiago Calatrava LLC

Editor: Kristen Evangelista