Born 1974, Los Angeles. Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

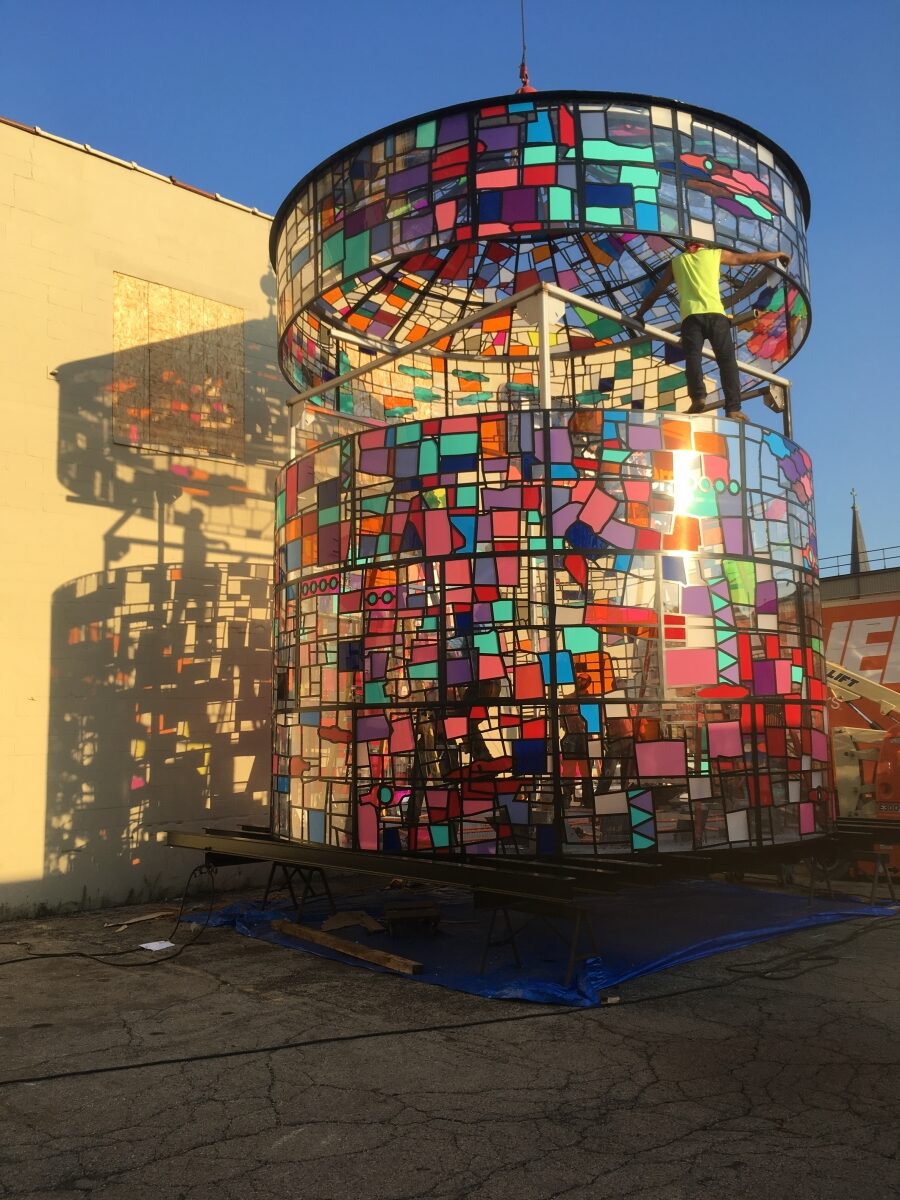

Tom Fruin makes public sculpture that’s hard to miss and easy to love. His works—houses, water towers, windmills—glow with saturated color and an open sense of joy. Built from reclaimed steel and found plexiglass, they’re formal yet accessible, architectural but handmade, and they wear their transparency like a badge.

Fruin emerged from a background in found-object assemblage, and the instinct to patch together fragments into something cohesive, something hopeful, still runs through everything he makes. The sculptures nod to the structures we overlook: infrastructure, vernacular buildings, utilitarian design. But he turns them into shrines of color and light.

The Watertower series, probably his best-known work, has become a quiet icon of the New York skyline. Fruin’s towers aren’t monumental in the usual sense. They don’t dominate the city, they sit with it. That’s part of their power. They don’t impose, they offer. You catch them unexpectedly, from a cab, on a rooftop, walking to the subway. And they stay with you.

There’s something democratic in Fruin’s approach. His work doesn’t hide behind walls or hedge its meaning. It lives in the city, changes with the light, and invites everyone in.

An Interview with Tom Fruin

When Art Lights Up: The Towers That Transformed the Urban Landscape

In your pieces, the brightly colored houses convey joy and rebirth. What do you remember from your childhood home in L.A.?

I grew up at the beach in California; I clearly remember the warmth of the sun and the endless sky. My mom used to time our dinners to coincide with the sunset. The colors from our dining room table were endless and dramatic.

In recent years, your sculptures have become New York icons, resembling structures like houses, water towers, and windmills. How did you choose to specialize in representational sculptures?

I find inspiration in the city, often modeling my work on overlooked infrastructure. Even if they are not typically considered attractive, functional structures like water towers, barns, windmills, billboards, and smokestacks can somehow embody the spirit of a place. I see the water towers as a touch of humanity in hard-edged New York; in contrast to the rest of the city, they are round, made of wood, and full of water–almost a stand-in for the human body.

Matt Canada

Your artworks are typically made using found plexiglass, reclaimed steel, and other materials. What is the creative process that brings a sculpture to life? What was the inspiration behind the concept?

The patterns and colors in the large Icon works are an extension of found object quilts that I’ve made. In an attempt to understand the city, I began collecting small bits of detritus on walking trips and organizing them into compositions. Quilts I initially imagined to be abject societal commentaries, ended up being fragile windows into our humanity and a celebration of life’s vitality! My large metal and acrylic sculptures attempt to monumentalize this exuberance. I use the quilts and found signage as inspiration for the patterns so the history of the material shines through and gives the work an added depth of lived experience.

Can you explain how you use light to create these projections?

I’d have to say the sun is the best light; it traces colorful projections around the sculpture as it tracks across the sky. However, at night the sculptures are transformed into beacons of kaleidoscopic color with the internal lights. I especially like to use programmed lights so the pieces seem to have a life of their own.

Your works appear in numerous public buildings and installations throughout NYC and in public places in other states. Where else in the world would you like to exhibit your works?

I love placing works in unexpected locations and reaching an unsuspecting audience. I look for sites that have a direct dialogue with the art. Sometimes it is nature, but increasingly I’m enjoying the urban environment as a backdrop for my art.

What things are essential in your atelier?

We listen to a lot of music in the studio: all genres. The pieces are complicated and labor intensive, and we fabricate them ourselves so I spend a lot of time in the studio. We need the music to keep going!

Editor: Kristen Evangelista