Interview

Artist: Shay Kun

Both of your parents, Zeev Kun and Heddy Kun, are artists. Did that influence your decision to become an artist, too? Do you remember when you decided to become a professional painter?

My acute awareness of my specific place in today’s visual culture, somewhere between the historical concept of fine art and the contemporary deconstruction of digital and electronic imagery as a central concept to his generation, places my work in juxtaposition with that of my parents.

As an artist, who began painting at the age of just three years old, and with both parents as commercial artists, I often wondered if becoming an artist was a part of his DNA. Both of my parents’ work is aimed at forging something new while creating artwork that is distinctly Israeli. My father’s work focuses on the decay and deterioration of landscape, while in contrast, my mother’s paintings look toward the celebratory aspect of landscape, growth, and nature in bloom.

For me, a series is never complete. I revisit each subject as my interpretation of reality and our ability to comprehend the representational evolves.

I remember myself in my childhood sitting down in my mom’s studio asking myself if these welcoming ‘greeting card’ paintings are in my genes. At that time, I could only produce a pastiche of Freudian, Van Gogh-type of work and this affliction of sublime testimony seemed too simple and sincere to justify. In retrospect I know today that both of my parents’ work shaped my style, those untouchable materials in my youth and through my education became the only motives that put a choke hold on me and did not let go. My exploration is not a tongue in cheek, a one liner of an Israeli artist flipping the European/ American sublime, but an emotional exploration of the point of departure between my mom’s celebratory landscape and my Dad’s decaying and deteriorating ones and how I can add to that my small voice liquefying this ‘unfinished symphony’.

There’s incredible creative energy in looking at what you were given as you grew up and then making a version of it later on. You make it with much more knowledge and intelligence. It’s like, ‘You’ve given me this, so I’m giving you that.’ Of course, it depends on what point you want to make; art can seem angry or you can take the anger and change it and make art that doesn’t seem so angry. Anger has been done to death recently. How do you take that spirit but not copy its product? Or can you apply that spirit to where it is least expected?

Currently you’re known as New York artist. What prompted your move from Tel Aviv?

I wanted to stop living through catalogs and books and see what the world has to offer. Israeli art is a bit like Israeli sports: we think we are in the center, but we really are not ☺. I got into Goldsmiths College in London to pursue my M.F.A., one of the most prestigious colleges in the world where the YBA generation (Young British Artists) was born and bred, and that experience opened my eyes to a whole new arena. Once I got the reality check and tasted the difference, I decided I’ll only go back for ‘my retirement’.

My works are very much inherited and routed in two separate lines: my fascination with soldiers/army life through my own experiences in Israel, serving in the army, and the perception and alternations of that in computer games, simulation, and other ‘disaster’ spectacles. I try to infuse my serene scenarios – which combine many times a hybrid of American-Israeli landscape of the midlands with the simulated touch of synthetic feel when art is transformed through technological means and being repainted – I try to inject my personal stories and visions.

As a contemporary painter, the suburban interests me. And the domestic – lots of European artwork is domestic, you can’t get away from it. It’s a complete continent fascination. For example, if it’s made by a British artist or the artist lives in Britain, they’re going to do works around the kitchen, the bathroom, the bedroom, getting up, having dinner. If you look through the whole of British art, it is always about that. Making Conceptualism and Minimalism domestic was the late 80’s. You can’t fight the domestic in western culture, its part and parcel of one’s national cliché.

I like suburban trash. I like suburban culture. I like the idea of not making a connection with the coolness of the center. There’s something kind of low-grade about suburban values, and there’s something about getting it right and getting it wrong at the same time. Suburban culture bastardized the mainstream, but not necessarily in an aggressive, punky way.

On the other hand as a first generation holocaust survivor, a son of two second world war immigrant artists, in many ways my practice is a reaction or negation to what was the conventional Israeli tradition of nature painting, where my parents too found themselves excluded as they were brought up by east European values. My work infuses both their styles while taking it to unmapped territories. The transformation I have in the works is almost like an ‘Israeli gypsy’ that has all the positive signs of missing his motherland. 🙂

What do you love most about living in Manhattan? How does it influence your work?

24/7 access, its ever-changing landscape, and the endless amount of cultural exploration which many aspects consume/ permeate my works as well.

What do you believe is a key element in creating a good painting?

Forgetting what you believe a good painting is.

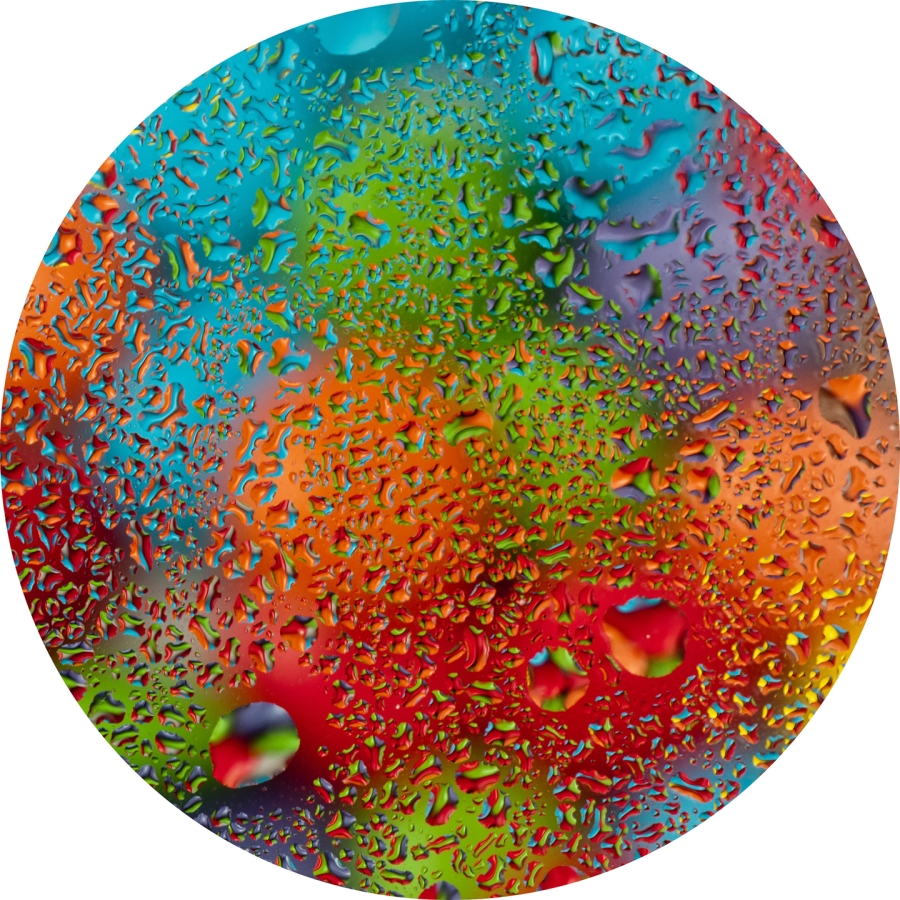

Can you tell us a little bit about the “Lift Off” series and about the influences and inspirations behind this body of work?

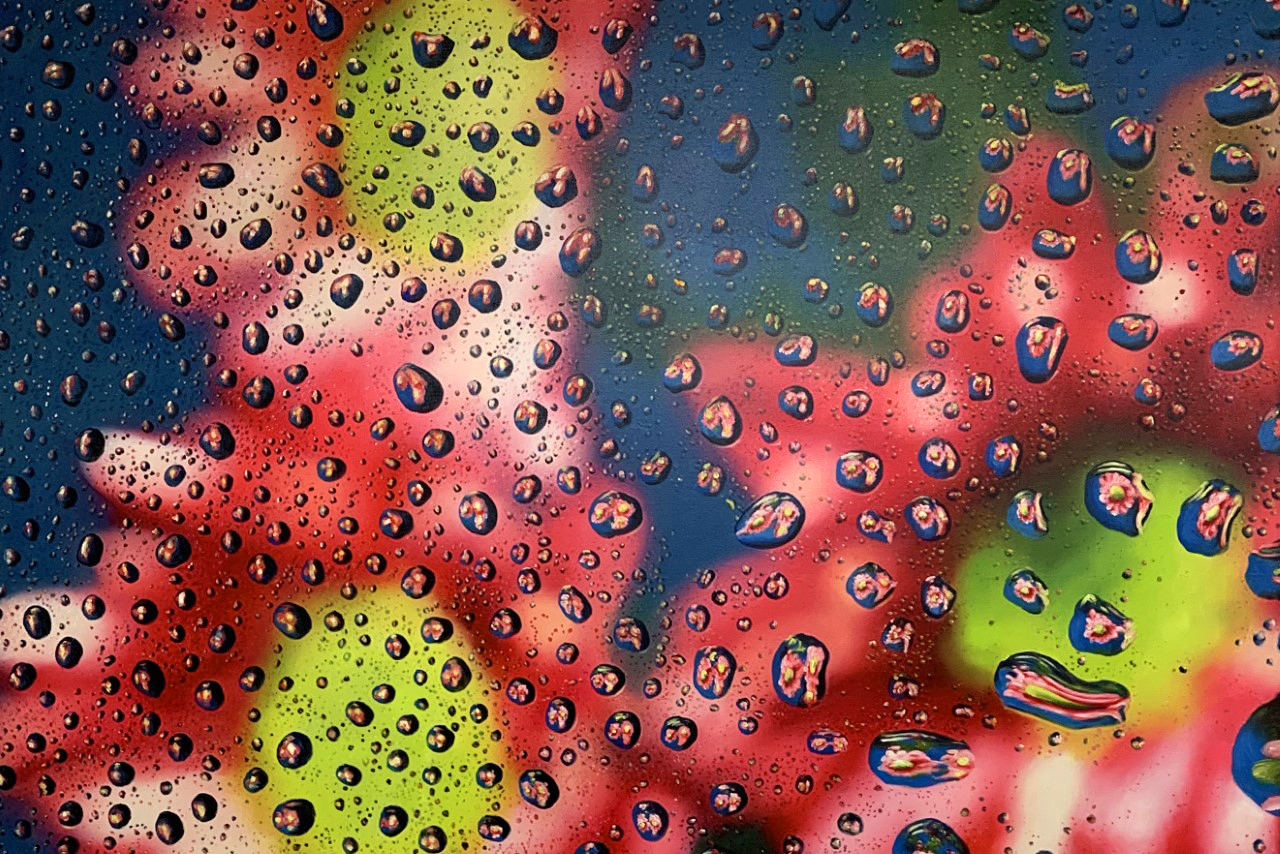

In this newest series of paintings, I inverted the relationship between natural and artificial. There is no time/space continuum in the background but the foreground remains anchored in the literal world of the hot air balloon. As we drift into the atmosphere, would the earth look warped? The paintings also reference the paradigm shift brought about by some noted explorers that the earth is actually round, not flat. But as we dig deeper into the archeology of knowledge, to borrow a phrase from post-modernity, we realize that Ptolemy the Greek geographer and mathematician of 150 C.E. amassed knowledge from the Alexandria library that the earth was in fact spherical. This knowledge came to be lost and in medieval times people thought the world was flat again. How did something that is a universal truth come to be lost during history? These paintings may describe the intellectual thought of when humans rediscovered the earth was flat. If they had risen in a hot air balloon high enough and looked down, they may have believed that the earth looked like one of the quadrants of these paintings. This relativity towards knowledge and time fashions my work. There are no absolute answers or truths. They are all just theories, some of which are better than others.

My personal angle and not just the intellectual scope: the celebratory optimistic attitude actually permeates from a charged source material which I refer to as ‘Holocaust Memorabilia’ – toy like artifacts that were carved out of wood by my parents (both established well-known artists in their own right) during hiding and brought back after the war – I took these relics, nurtured them back into life, repainted them, and took them to a different journey involving escapism and fantasy.

What do you find the most challenging/rewarding aspects of being a professional artist?

I think my work does not look sophisticated in the way that the previous generation does, because the previous generation in Israel borrowed a very high-art, international look: they borrowed conceptualism and minimalism, and added their pop, cultural content to it. Choosing minimalism and conceptualism guaranteed international credibility. I did not feel the need to do that. I was lucky enough to attract an international art audience that is relaxed enough to know that you can make very sophisticated products from odds and ends. And not make it seem regional. It’s very international but it doesn’t need to prove it. The previous generation had a much more difficult task because they seemed to come from nowhere and they had to prove their internationalism. In the Wall Street corporate 80’s advertising money world, Minimalism and Conceptualism made sense. In the sitcom, goofy world of now, people can do small, low key things or have weird ways of working and fitting in. Artists didn’t make this change; the culture does. When art responds to culture, people get it. And when it doesn’t, then there’s confusion and anxiety because people don t get it. They don’t get what the art is trying to say.

Do you listen to/watch any form of media while working? If so, what is it and how does it influence your process?

I listen to podcasts mostly about MMA (mixed martial arts). It’s a passion of mine that keeps me super focused and inspired.

Can you tell us a little bit about your future plans, new projects?

I am currently working on shows for 2020-2021 in Boston, Tel-Aviv, Vienna, and Paris, some with new galleries and some with older familiar faces. I am also collaborating on a new art project duo which will consist of many elements/moving parts from paintings, sculptures, photography, fashion, products, editions, online presence, and many other narratives under the brand name Confu$ius…stay tuned.

Your favorite quote is … “Live and Let Live”